Clambering onto train tracks and sneaking into subways to find nooks and crannies for his graffiti, a Beijing street artist with the tag name Wreck says it takes guts and luck to pursue his hobby in a city bristling with surveillance cameras and police patrols.

“I like to paint in challenging places,” says the lanky bespectacled 30-year-old with ear studs and a ponytail.

That includes artistic sorties into Beijing landmarks like the trousers-shaped CCTV headquarters and the Nanluoguxiang shopping area, places with huge flows of people during the day but quiet at night.

“There are graffiti carnivals where artists paint in designated zones. But working in such a pressure-free way is quite meaningless,” says the Beijing native, a tattooist by trade, who wants to remain anonymous to avoid drawing attention to his lawbreaking pastime.

A member of the KTS (Kill the Streets) crew, Wreck has only been fined twice for defacing public property even though he has been a graffitist since high school.

“The fine was around 2,000 yuan [US$310],” he says. “You can negotiate with the police, saying you are only making doodles and doing nothing subversive. The police let me go without detention.”

Chinese mum pays over US$150,000 to have ‘perfect’ seven kids

Former graffiti artist Yang Xuan, 31, who now works making ceramic tea sets, says he has never heard of anyone getting arrested for spraying graffiti in China. “But sanitation workers can quickly remove our works,” he says. “On quieter days with no big government events, the works can stay for one to two months. Some works disappear the next day.”

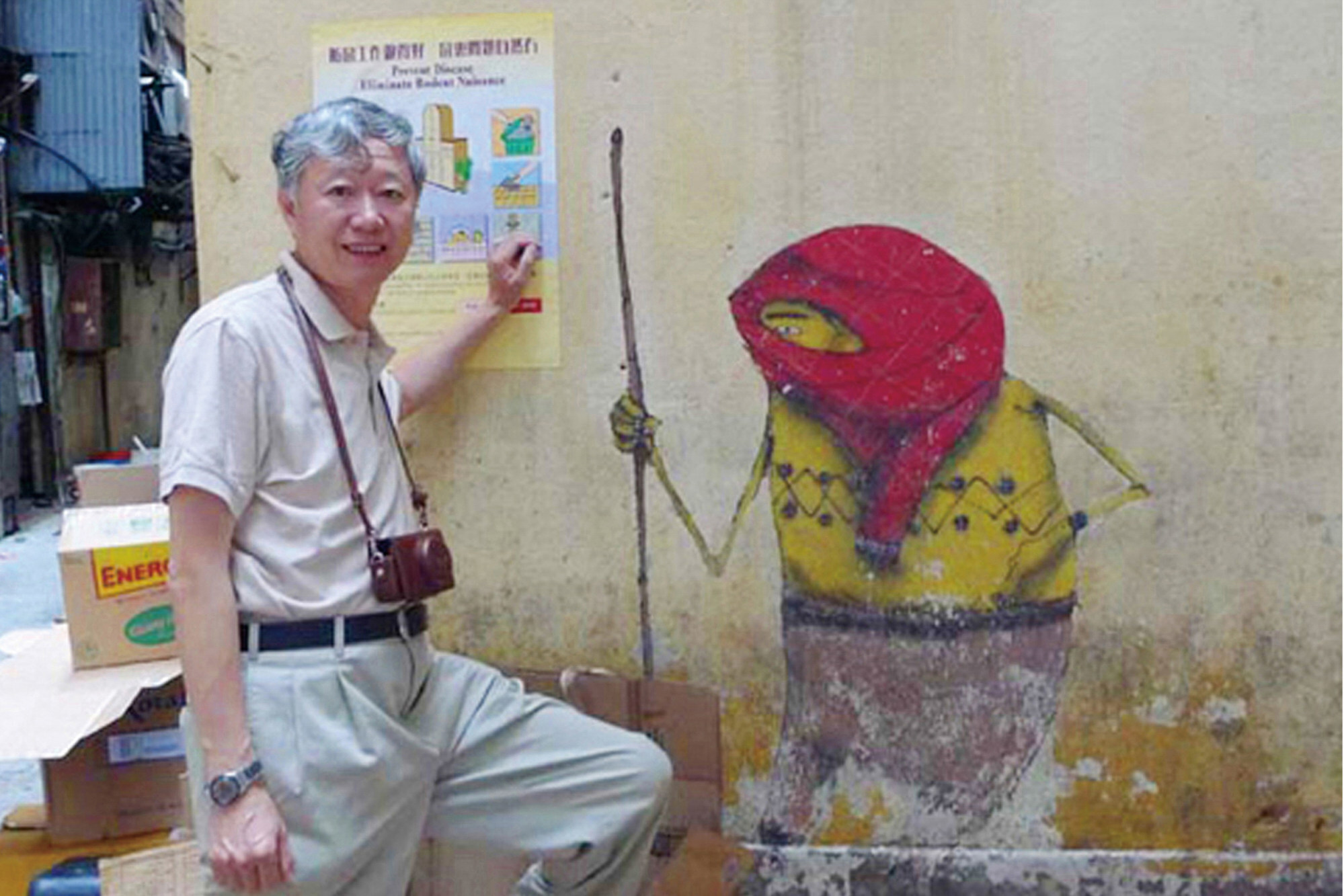

Stung by the impermanence of street art, Liu Yuansheng, 67, started photographing graffiti in Beijing in the late 1990s, endearing him to dozens of graffiti artists who tip him off whenever something new has been painted.

Working as a senior editor for a state-run magazine before his retirement in 2014, he spends most of his spare time traversing Beijing’s warren of alleys to find graffiti. More than 300 of his photographs have been compiled into a new English book – Beijing Graffiti – recently released by Schiffer Publishing in the US.

Liu says he is happy a Western company wants to publish his works. “No local publishers want to publish my pictures due to the sensitive nature of the subject,” he says, referring to the illegality of the activity.

In 2017, Liu spent 18,000 yuan to publish two graffiti photo books totalling 400 copies. In 2019, he financed a third photo book.

“Taking graffiti pictures is like stamp collecting to me,” he says. “The more stamps I get, the better. Graffiti works are ephemeral in nature. By documenting them, they can last forever.”

Beijing Graffiti co-author Tom Dartnell, a former graffiti artist from the UK who was active in the ’90s, says he discovered Liu after watching the documentary Spray Paint Beijing (2014) directed by former China Daily video producer Lance Crayon.

“Liu is the last person you would expect to be into graffiti,” Dartnell says. “If you saw a 50-year-old guy in the West taking photos of graffiti, you would think he is an undercover policeman.”

Dartnell says Schiffer Publishing is interested in Liu’s works because “Beijing is one of the last places you would expect this subculture to exist”.

He says graffiti has a better image in China than it does in the West. “In the UK, the police really go after graffiti artists,” he says. “I know someone who went to prison for 18 months just for doing graffiti there.”

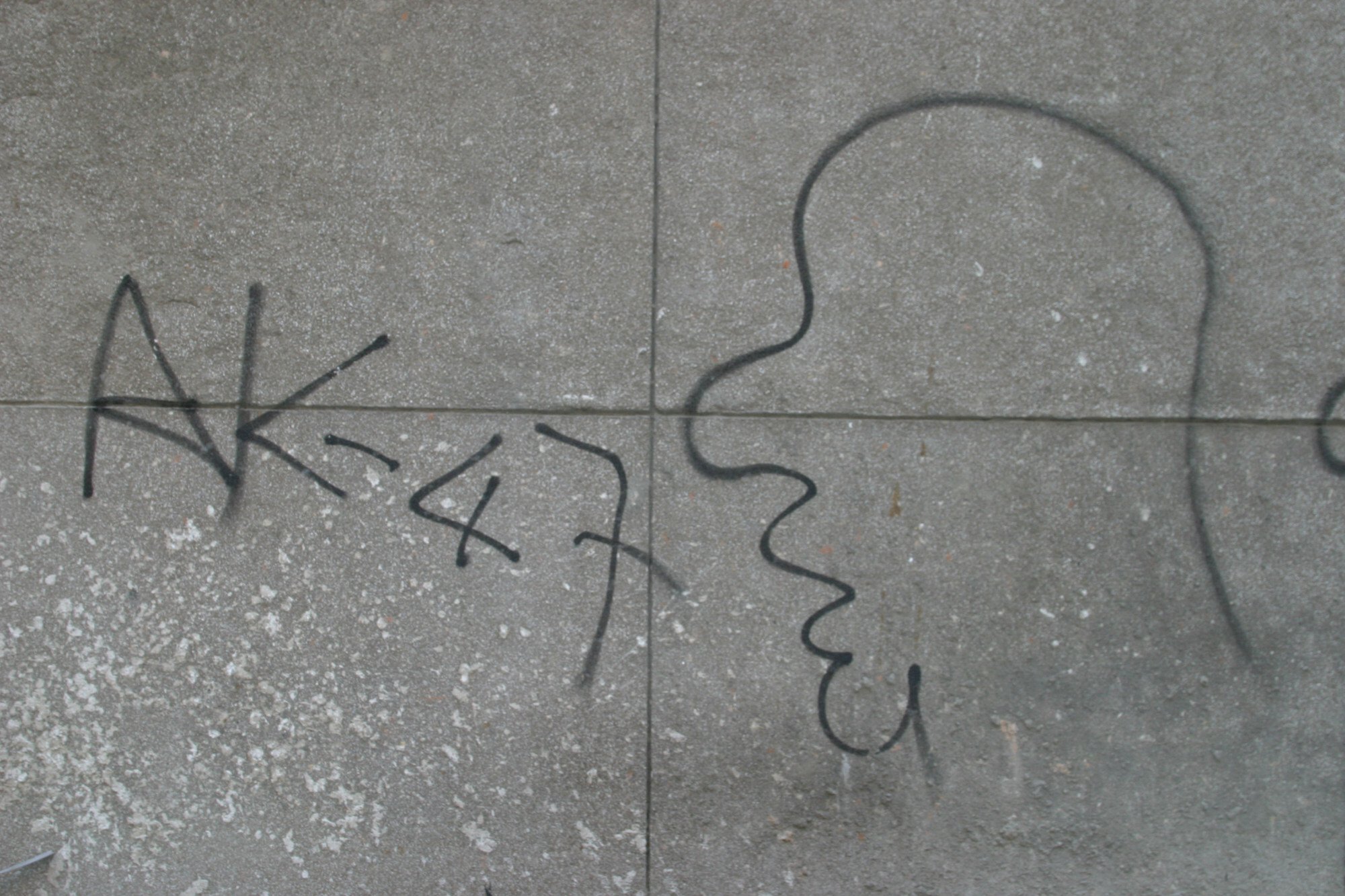

The book includes photos of work by the first graffiti artist in China, Zhang Dali, who moved from Beijing to Italy in 1989. Having imbibed Western art traditions, Zhang returned to Beijing in 1995 and started spray-painting giant rough profiles of his own bald head on buildings that had been marked with the Chinese character “chai” that indicated their imminent demolition. His 2,000 works, often with his tag “AK-47”, were seen as a veiled attack on rampant demolition and urbanisation.

Beijing Graffiti features myriad styles that incorporate both Western pop culture and Chinese motifs including dragons, pandas and paper-cutting. The works were photographed on tree trunks, car park walls, bridge girders, shop shutters, semi-demolished buildings – anywhere away from Beijing’s ubiquitous security cameras.

The book includes interviews with 25 graffiti artists from various crews who explain how they cut their teeth in the subculture. The crews first emerged in Beijing in the early 2000s: first Kwanyin in 2006, followed by BJPZ Crew and ABS in 2007, then KTS a decade later. ABS opened 400ml – the first specialist shop selling aerosol paint in China – in Beijing’s 798 Art Zone in 2012 (400ml is the volume of a can of spray paint).

Graffiti crews also popped up in other cities (MIG in Guangzhou, Venus in Wuhan and PEN in Changsha). One-time graffitist Yang says his crew scoped out potential venues for graffiti from public buses. “We liked conspicuous places frequented by lots of people,” he says. “We used to paint under Baishixin bridge [in Beijing’s Haidian District]. All the cars on the two lanes under the bridge could see our works.”

Many of Beijing’s graffitists are skateboarders, hip hop enthusiasts and street dancers, with the popularity of graffiti throughout China increasing with the influence of Western subculture and local television hits like Street Dance of China and The Rap of China.

Beijing’s municipal government has sometimes incorporated the edgy art form into urban design, setting aside wall space for students to paint patriotic murals in the run-up to the 2008 Olympics and designating areas including Tiancun Road in Haidian as graffiti zones.

In 2010, ABS organised the first “Meeting Neighbourhood” festival in Beijing, a now annual street culture carnival mixing graffiti, accessory-making and tattoo workshops, retrofitted cars, and DJ music. In 2012, one of the leading figures in the New York graffiti scene, Terrible T-Kid 170 from the Bronx, was invited to paint and exhibit work at a gallery in Beijing.

Subway operators in many cities including Wuhan, Beijing and Chongqing have commissioned graffiti-style artwork in their stations.

Graffiti has become profitable in China. Many graffitists create designs for sports brands, restaurants and other hipster hang-outs. ABS set up a company in 2012 to manage their booming business.

Former graffitist Yang says ABS and Wreck are on opposing sides of the spectrum. “The skills of Wreck and his peers are more rudimentary, but their underground artistic ventures retain the original elements of graffiti,” he says.

While many international artists like the elusive Banksy use graffiti to make political statements about government repression and social ills, many Chinese artists say politics is non-existent in their work.

The cost of painting graffiti critical of the government is too high, says a 29-year-old artist with the tag name Poste. “I vent my anger through graffiti,” he says. “But that is not so much anger about society as youthful angst.”

Wreck, by contrast, says the increasing gentrification of Beijing means he has fewer and fewer chances to pursue his passion. “The best time for graffiti was around the early 2010s when the city was dotted with construction sites,” he adds. “Now, high-end neighbourhoods with glassy structures are everywhere. Graffiti doesn’t match with such sanitised surroundings.”

For his part, Yang says he stopped spraying graffiti in 2014 because of his fear of the police. “I didn’t care about getting caught when in university,” he says, adding that his job has made him more cautious.

Yang says cities like Guangzhou, Wuhan and Chengdu are the new cool hang-outs for graffiti artists.

A 30-year-old artist from Chengdu who paints with the tag Dens says the city’s vibrant graffiti scene flourishes because there is slower urban development, fewer government controls and more laissez-faire social norms.

“From the Bus Rapid Transit on the second elevated ring road, people can see a lot of colourful graffiti dotting buildings’ rooftops,” he says. “Some of my works are still there after four or five years.”