Satellites orbiting Earth to gather images and measurements of land, forests, cities, and coastal waters have helped scientists understand our planet.

However, since these images come from many different sources, it can be difficult to combine them into a single picture.

Google’s artificial intelligence (AI) unit, DeepMind, recently announced an AI model called AlphaEarth Foundations that can create highly detailed maps of our world in nearly real time.

AlphaEarth Foundations functions like a “virtual satellite” that maps the world “at any place and time,” Christopher Brown, a research engineer at Google DeepMind, said at a press briefing in July.

“Whether they are monitoring crop health, tracking deforestation, or observing new construction, [researchers] no longer have to rely on a single satellite passing overhead. They now have a new kind of foundation for geospatial data,” Google DeepMind wrote in a statement last month.

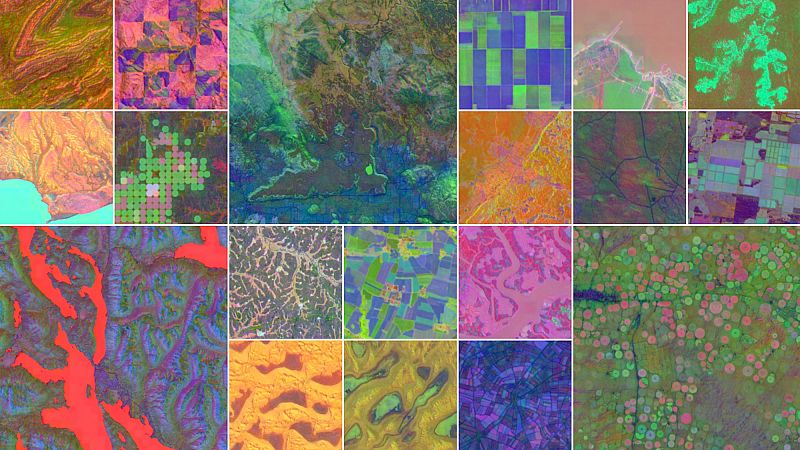

The system combines trillions of images from dozens of public sources, including satellite images, radar scans, laser-based 3D mapping, and climate simulations. It maps the entire planet’s terrestrial land and coastal waters.

Google said the model can generate accurate enough data about an ecosystem down to an area of 10 square metres. Data from AlphaEarth Foundations takes up far less storage space than similar AI systems, which makes large-scale analysis more practical, the company said.

During AlphaEarth Foundations’s initial testing of data from 2017 to 2024, it beat similar AI models in identifying land use and estimating surface properties, with an average error rate that was 24 per cent lower, according to a paper published by DeepMind.

Google hopes it will help researchers study changes across the planet for food security, deforestation, urban expansion, and water resources.

Why scientists want this level of detail and how AI can help

AlphaEarth Foundations is part of a growing trend in environmental science where AI turns the constant stream of satellite observations into practical tools for studying the Earth.

High-resolution, regularly updated data help researchers measure environmental changes precisely and understand what is driving them.

They can be used to track the effects of climate change, plan conservation, and manage resources like water and farmland.

For example, in 2020, scientists at NASA and the University of Copenhagen mapped 1.8 billion individual tree canopies in the Sahel and Sahara regions of west Africa, using AI trained to recognise trees in satellite images.

Without AI, this would have taken millions of people years to complete, according to the study authors.

Since 2022, NASA’s Surface Water and Ocean Topography (SWOT) satellite has been taking high-definition measurements of oceans, lakes, reservoirs, and rivers over 90 per cent of the world's surface.

NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) said it could observe water on Earth's surface with 10 times greater resolution than existing technologies.

Meanwhile, the European Space Agency (ESA)’s EarthCARE satellite launched in 2024. It is studying how clouds and airborne particles in the atmosphere impact the Earth's temperature.

Much of Google DeepMind’s data also comes from long-running missions from NASA and ESA, such as the Landsat and Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) satellites and the Sentinel fleet, all of which monitor vegetation, coastlines, water bodies, snow, and ice.

Google says its model has already been tested by more than 50 organisations around the world for ecosystem monitoring and urban planning.

For example, an environmental initiative in Brazil known as MapBiomas is using AlphaEarth Foundations’ data to better understand agricultural and environmental changes, including in the Amazon rainforest.

The model’s annual datasets have given the team “new options to make maps that are more accurate, precise and fast to produce, something we would have never been able to do before,” said Tasso Azevedo, the founder of MapBiomas, in Google’s statement.

Google says it is releasing the dataset through Google Earth Engine, Google’s environment data platform, to encourage further research.