Everyone over the age of 20 will tell you that the Britain they now inhabit is different from the Britain they knew in childhood – that certain things they thought would always be there have since melted into oblivion. Sometimes all they mean is old television programmes or outdated technology. But often there’s a deeper nostalgia at work – a memory of empty fields that later became housing estates, or of high-street shops (the greengrocer’s, the ironmonger’s) before chain stores took over. Progress comes at a price. For every startup there’s a shutdown, for every labour-saving innovation a manual job consigned to history.→

Photograph: Zed Nelson/INSTITUTE

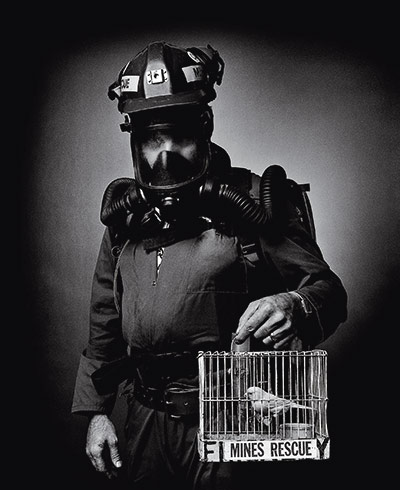

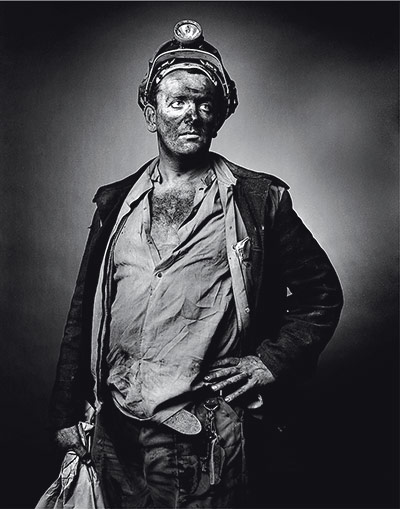

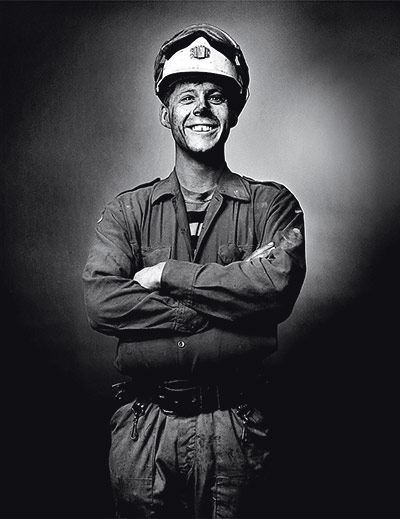

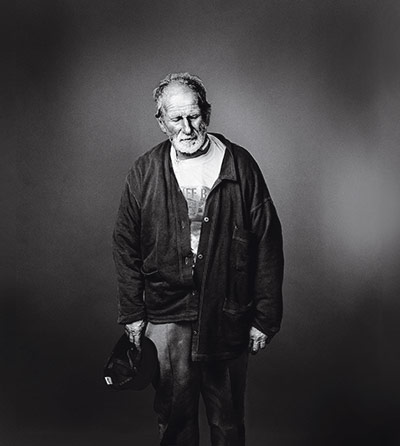

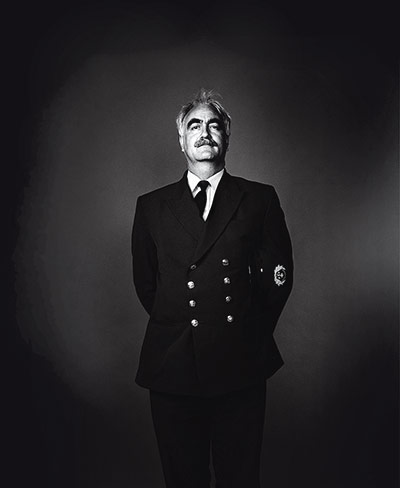

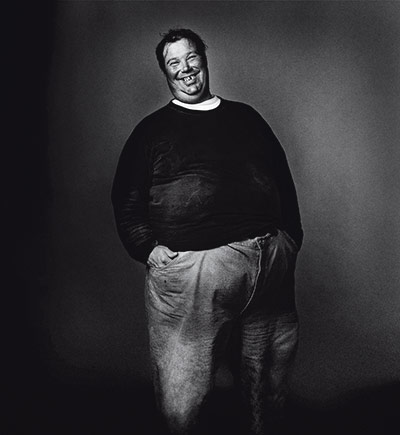

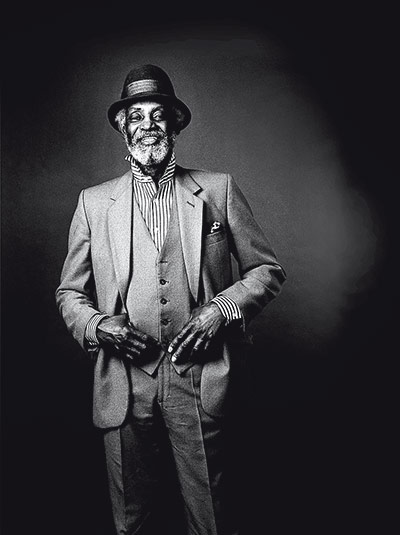

The photographer Zed Nelson is no nostalgist. He knows that some change is natural and inevitable. And his work – more urban than rural in emphasis – is anything but quaint. But in recent years he has been taking photographs that commemorate long-established national traditions, whether those of work (coalmining, fishing, shipbuilding) or of sport (foxhunting and boxing). The decline of these industries and leisure pursuits has been well documented in news stories. But what interests Nelson is the human dimension: faces and bodies, helmets and uniforms, rather than arguments. There’s a political subtext nevertheless. His photos preserve disappearing strands of our culture and ask whether we’re happy to see them go.→

Photograph: Zed Nelson/INSTITUTE

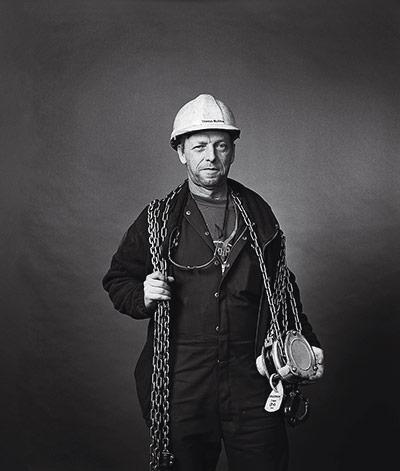

Nelson's project began in the early 1990s, with photographs of miners from the Maltby colliery in Yorkshire, a pit since sold off and saved but which at that point was one of 30 earmarked for closure by the Conservative government. Nelson built a studio at the top of the mine-shaft and persuaded the men to pose for him as they came off their 10-hour shift – no easy matter, when they were tired, desperate for a shower and preoccupied by fears of redundancy. The photos are beautifully lit, unlike the mines from which the men have ascended. One man, a safety officer, carries a canary in a cage – an early-warning system for detecting carbon monoxide that dates back at least a century. To look at the men, many of whose fathers and grandfathers worked in the same pit, little else has changed either: these might be images from the 1930s. →

Photograph: Zed Nelson/INSTITUTE

Photograph: Zed Nelson/INSTITUTE

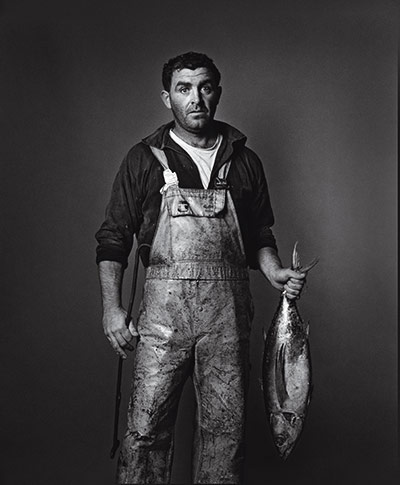

Nelson’s portraits of Cornish fishermen were created in a similar way: he built a studio in a wooden hut on the harbour at Newlyn and photographed the men as they came off their boats after hunting tuna in the Bay of Biscay. Alone or in groups, the fishermen grimly hold their catches, as if too angry about restrictive fishing quotas and resentful of foreign boats invading their waters to take pleasure in their haul. →

Photograph: Zed Nelson/INSTITUTE

Photograph: Zed Nelson/INSTITUTE

Photograph: Zed Nelson/INSTITUTE

Photograph: Zed Nelson/INSTITUTE

Photograph: Zed Nelson/INSTITUTE

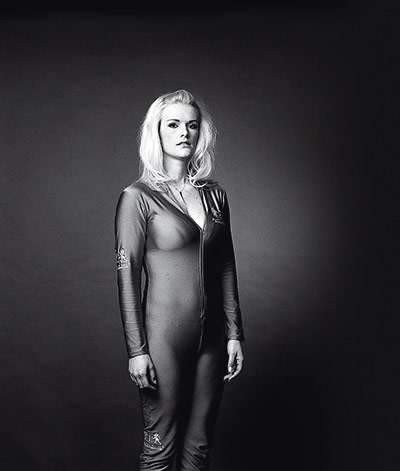

The Clyde shipbuilders Nelson has recently photographed look as doom-laden as the fishermen, though their gear is hi-tech and futuristic. One of them is a woman, whereas the shipbuilders photographed by Bert Hardy for Picture Post 60-odd years ago were exclusively male. The disappearance of ancient gender divisions isn’t a cue for celebration, though. Here, too, is a twilight industry. As shipyards dwindle, any job is likely to be short-lived. →

Photograph: Zed Nelson/INSTITUTE

Photograph: Zed Nelson/INSTITUTE

Photograph: Zed Nelson/INSTITUTE

Photograph: Zed Nelson/INSTITUTE

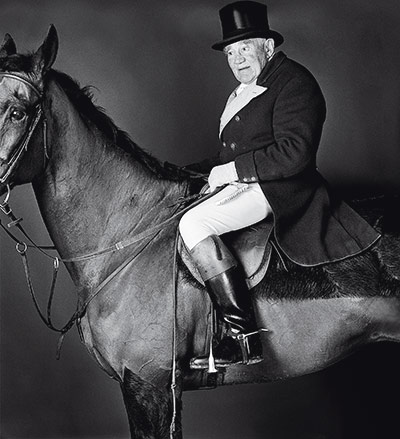

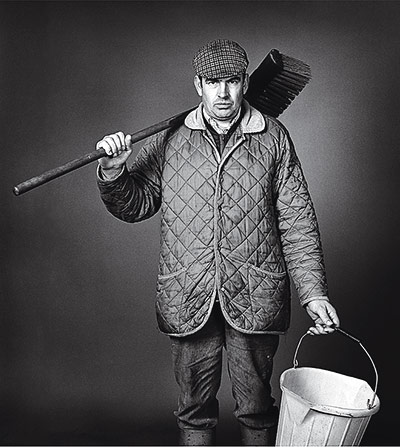

Nelson’s portraits of British workers are brightly lit in the manner of Richard Avedon: formal yet intimate, they pay homage to ordinary lives. Taking photos of Beaufort foxhunters was more of a challenge – not just because it meant Nelson finding a studio large enough to accommodate a horse, but because his sympathies are anti-bloodsport. Over time he grudgingly accepted some of the pro-hunting arguments, not least that the pursuit of “vermin” brings jobs to poor communities. The photos are respectful of their subjects rather than (as, say, Martin Parr might do) sending them up. Kennel and terrier men feature, as well as toffs. And among those on horseback is an embattled 80-year-old émigré, who remembers hunting being banned in Hitler’s Germany. →

Photograph: Zed Nelson/INSTITUTE

Photograph: Zed Nelson/INSTITUTE

Photograph: Zed Nelson/INSTITUTE

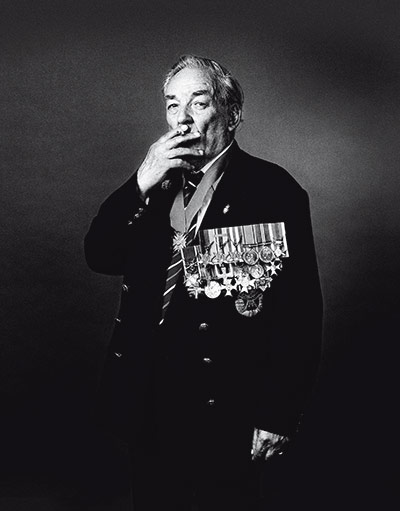

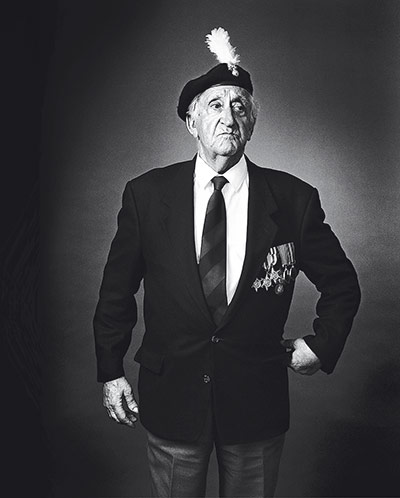

The most moving images come from veterans of the second world war, a group disappearing from Britain not because the army is surplus to modern requirements (if only) but because they’re old and slowly dying off. Weighed down by medals, the veterans stare out impassively, as though drilled to keep a stiff upper lip. →

Photograph: Zed Nelson/INSTITUTE

Photograph: Zed Nelson/INSTITUTE

Photograph: Zed Nelson/INSTITUTE

Photograph: Zed Nelson/INSTITUTE

Photograph: Zed Nelson/INSTITUTE

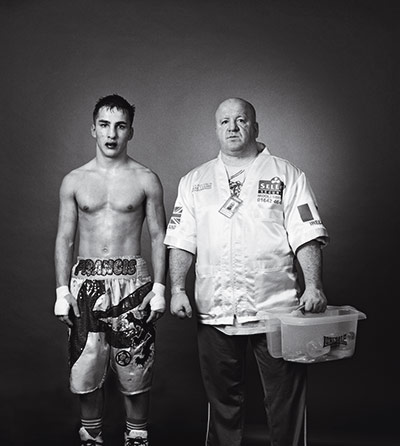

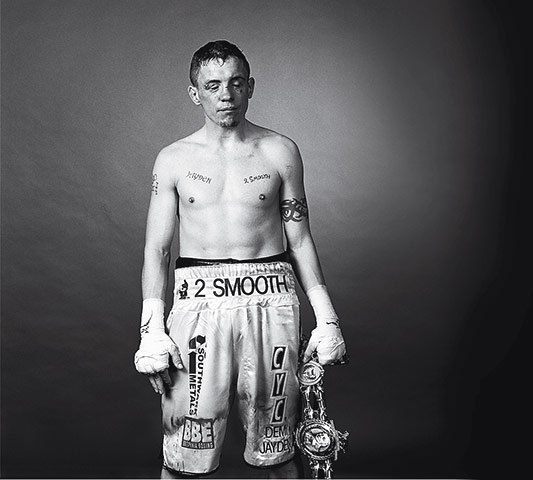

A younger breed of fighting men appears in Nelson’s photos of boxers. The sport came under threat some years ago after a series of deaths and brain injuries but has since implemented various safety measures, only to be faced with a new reason for extinction – the growing popularity of a rival martial art, cage fighting. If Nelson’s boxers seem forlorn, it’s not so much because they’ve been bruised and battered in the ring as because their skills are no longer in demand. →

Photograph: Zed Nelson/INSTITUTE

When Henry Mayhew documented the trades and scams carried out by London’s Victorian poor – the curriers, costermongers, muffin-men, river-finders, mudlarks, crossing-sweepers, ballast-heavers, rubbish-carters, garret-masters, pewterers, powder-makers, tallow-chandlers, etc – he’d no idea how quickly they would slip into history. Of course we’ll always need food, transport and energy. But now we can get them more cheaply elsewhere, our own producers – Cornish fishermen, Glasgow shipbuilders and Yorkshire miners – are being sidelined. That’s why Zed Nelson’s photographs make such a poignant archive: a record of what British workers looked like, when there was still the work.

Photograph: Zed Nelson/INSTITUTE

Photograph: Zed Nelson/INSTITUTE

Photograph: Zed Nelson/INSTITUTE