The challenging U.S. labor market is entering a new normal, according to Goldman Sachs economists David Mericle and Pierfrancesco Mei, who tackled the phenomenon of “jobless growth” in an Oct. 13 note. It resonates with what Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell memorably described in September as a “low-hire, low-fire” labor market, in which, for some reason, “kids coming out of college and younger people, minorities, are having a hard time finding jobs.”

Some analysts blame the downturn in entry-level hiring on the impact of AI on the economy, others on macroeconomic uncertainty, especially the seesawing tariffs regime from the Trump administration. The takeaway is clear, though, that getting hired is really hard in the mid-2020s.

“The modest job growth alongside robust GDP growth seen recently is likely to be normal to some degree in the years ahead,” Mei and Mericle wrote, adding that they expect the great majority of growth to come from solid productivity growth boosted by advances in artificial intelligence, “with only a modest contribution from labor supply growth due to population aging and lower immigration.”

The key question is whether the trend of jobless growth will continue, with an era of “job hugging” likely to persist. In an ominous note, the economists cite the track record of how big labor shifts tend to play out: “History also suggests that the full consequences of AI for the labor market might not become apparent until a recession hits.”

Productivity outpacing job creation

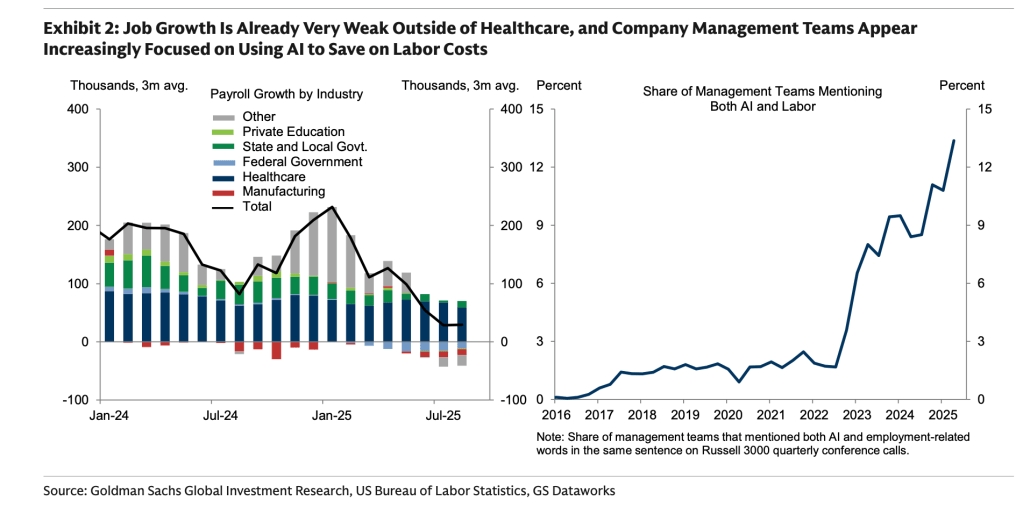

America’s economy continues to expand, with real GDP growth projected to remain steady and respectable, even as monthly payroll growth lags well behind historical recovery averages. Goldman Sachs researchers say most of the nation’s output gains will come from productivity improvements—largely powered by rapid AI adoption—while demographic trends like population aging and lower immigration hold down labor supply growth. The result: Hiring activity outside of health care has turned negative on net in recent months, while management teams in many sectors are focused on using AI to streamline operations and cut labor costs.

This shift is clear in data collated by the investment bank. Payroll growth by industry shows almost all sectors outside health care posting weak, zero, or even negative net job creation, despite otherwise solid macroeconomic indicators. Meanwhile, the share of executives who mention both AI and employment in the same context on earnings calls has reached historic highs.

Goldman finds the labor market to be “somewhat weaker” than just before the pandemic, with job growth turning net negative in recent months outside of health care, and company management teams increasingly focused on using AI to reduce labor costs, “a potentially long-lasting headwind to labor demand.”

Federal Reserve governor Chris Waller told CNBC’s Steve Liesman the previous week that, notwithstanding the government shutdown and lack of government jobs data, the alternative data are all telling a similar story. “Job growth has probably been negative the last few months,” he said, prompting an exclamation from his interviewer. “If you have negative job growth, that’s not maximum employment, where you’re shrinking your hiring,” Waller said, arguing that the central bank is not fulfilling the employment half of its dual mandate.

The ‘low-hire, low-fire’ labor market

Goldman’s analysis is measured, as Mei and Mericle write they are “skeptical of the boldest claims that rapid technological progress could lead to very high unemployment,” citing their global economics colleagues who argue that innovation and greater spending power will create new opportunities. Relatedly, the Nobel Committee awarded the economics prize earlier this week to economists who specialize in studying “creative destruction,” the same dynamic Goldman is describing here. That being said, Mei and Mericle add dryly, “Some transitional friction has been normal historically and is certainly possible in the future.”

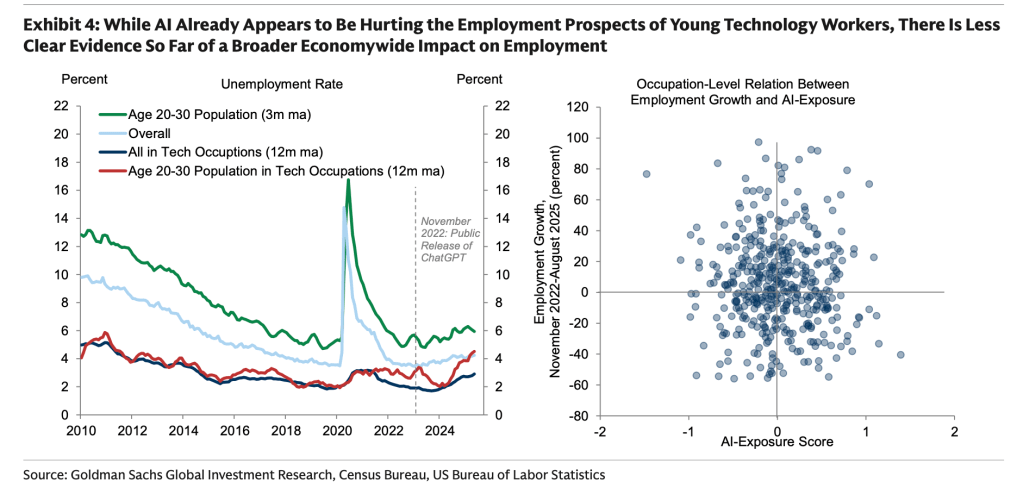

Mei and Mericle do find that AI appears to be hurting the employment prospects of young technology workers, especially those in areas exposed to automation, while the overall macro impact is limited, citing similar research by economist Erik Brynjolfsson and the Yale Budget Lab.

Risks and opportunities in the ‘jobless’ future

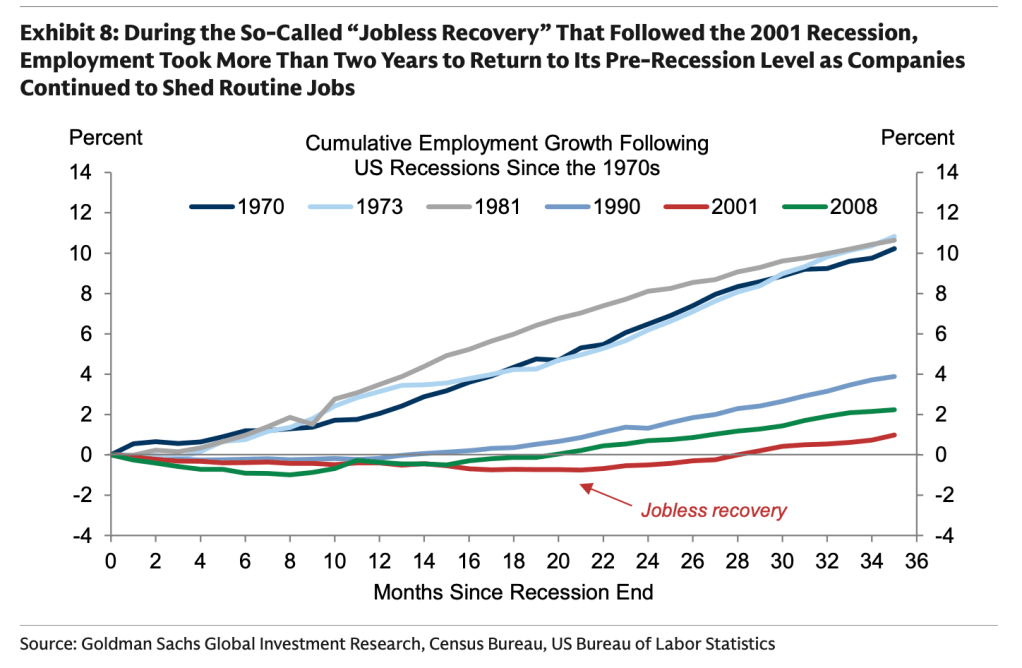

The Goldman report also examines the risks and broader implications. History suggests that the full consequences of AI for the labor market may not appear until the next recession hits, citing a leading explanation that “companies use recessions to restructure and streamline their workforce by laying off workers in less productive areas.” This is especially true when recessions follow productivity booms, when overhiring may have occurred, they argue. Several top CEOs and economists have argued that the hiring binge known as the “Great Resignation” resulted in many overpaid workers with inflated job titles who have stopped churning out as the labor market slowed.

Goldman cites the “jobless recovery” of 2001 after the dotcom bubble burst. “During that recovery, despite a soft labor market, productivity growth remained elevated, and GDP growth rebounded earlier than employment growth.” Economists Alex Bryson and David Blanchflower previously told Fortune that their research on labor markets and young worker “despair” suggests that jobless recoveries could be the culprit, although they acknowledge that the wages and unemployment picture is much more positive. In some sense, then, the low-hire, low-fire labor market may be an acceleration of a condition familiar throughout the 21st century so far: improving productivity that doesn’t feel all that great to workers on very lean teams.

As “jobless growth” becomes entrenched, Goldman Sachs expects policymakers to face tough new choices. Central banks could be forced to keep interest rates lower in response to subpar job creation and modestly higher unemployment, while markets may see mixed effects. Asset prices could be supported by healthy output and low rates, but only if unemployment remains contained and new kinds of jobs emerge to offset losses caused by AI.

For now, Mericle’s “low-hire, low-fire” diagnosis serves as both warning and guide: Jobless growth may not mean mass layoffs, but it does mean fewer opportunities for job seekers and slower rebounds from economic shocks in the years to come.