Earth’s water cycle is becoming harder to predict as the climate changes, UN scientists have warned.

Last year was the sixth in a row to show an erratic cycle and the third where all glacier regions reported ice loss, according to the World Meteorological Organisation’s (WMO) state of global water resources report for 2024, released on Thursday.

The international group of scientists assessed freshwater availability and water storage across the world, including lakes, river flow, groundwater, soil moisture, snow cover and ice melt.

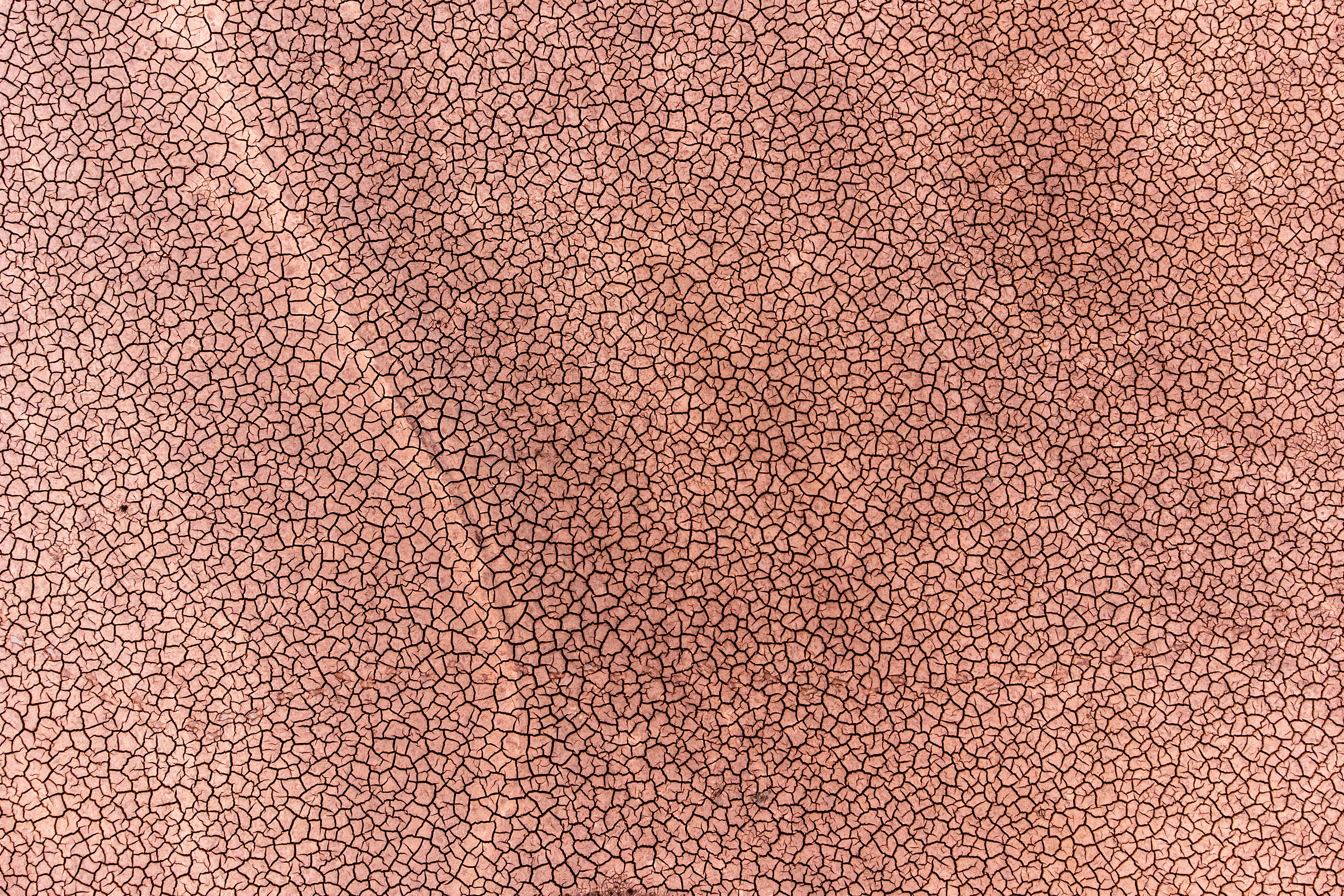

While 2024 was generally a dry and hot year, featuring record-breaking temperatures driven by the warming El Nino weather phenomenon, it also saw significant flooding events, the scientists said.

They found that around 60% of rivers globally showed either too much or too little water compared to the average flow per year.

While the world has natural cycles of climate variability from year to year, long-term trends outlined in the report indicate the water cycle, at a global scale, is accelerating.

Stefan Uhlenbrook, WMO director of hydrology in the water and cryosphere division, said scientists feel it is “increasingly difficult to predict”.

“It’s more erratic – so either too much or too low on average flow per year,” he said.

As global warming drives higher global temperatures, the atmosphere can hold more water, leading either to longer dry periods or more intense rainfall.

Mr Uhlenbrook said: “The climate changing is everything changing, and that has an impact on the water cycle dynamics.”

In 2024, only a third of river basins globally were found to have normal discharge levels, with most seeing too much or too little water flowing out to sea.

Mapping shows parts of Europe, central Africa, India and China saw wetter-than-average weather and some significant flooding events, while southern Africa and South America were among the regions that experienced dry conditions, including persistent drought.

In areas of Europe, snow had melted away to abnormally low levels by March, while areas of central Asia saw higher levels of snow that month, which then caused spring flooding, the scientists said.

They also found that the warmer atmosphere translated to higher-than-average surface temperatures in freshwater lakes.

In the UK, 2024 brought particularly wet conditions to the south and, with this, some record high river flows, yet large parts of northern England and Scotland saw below-normal to exceptionally low flows.

In contrast, 2025 saw one of the driest springs on record as well as the UK’s hottest summer on record, with many areas still remaining under drought status into autumn.

Lucy Barker, a senior hydrological analyst at the UK Centre for Ecology and Hydrology, said: “This has meant we’ve seen exceptional and significant impacts on agricultural water resources and the environment.”

Between 1975 and 2024, the world lost a cumulative 9,000 gigatons of ice from glaciers, which equates to roughly the size of Germany at 25 metres thick, the report said.

While there were some positive years for ice in the 1980s, the world is now seeing more and more negative years, with 2023 marking the most negative year with 540 gigatons of loss, followed by 2024 with 450 gigatons of loss.

Isabelle Gartner-Roer, group leader (glaciology) at the World Glacier Monitoring Service, said: “Glaciers are sensitive indicators for climate change, and monitoring is important, but most importantly… melting of snow and ice from the mountains is critical for the freshwater supply for many regions.”

Melting glaciers and erratic snow cover patterns can have a significant impacts on mountain communities, as well as those living downstream in the valleys and beyond, the scientists said.

The changes can damage agricultural output, harm ecology and wildlife, increase the risks of hazards such as landslides and floods, and threaten regional industries, economies and cultures.

“For some regions, absolutely (it is) existential,” Mr Uhlenbrook said. “The change of water dynamics does impact livelihood and economies significantly.”

Mr Uhlenbrook said investing in warning systems, monitoring, data, technology and research and water management is “critical.”

“It’s a very positive return on investment, and we cannot delay that any longer.”

Asked if governments are doing enough to prepare for changing water cycles, he said: “It varies per country and it doesn’t get sufficient attention.

“Government(s) should pay more attention and should see this as a valuable investment in their society.”