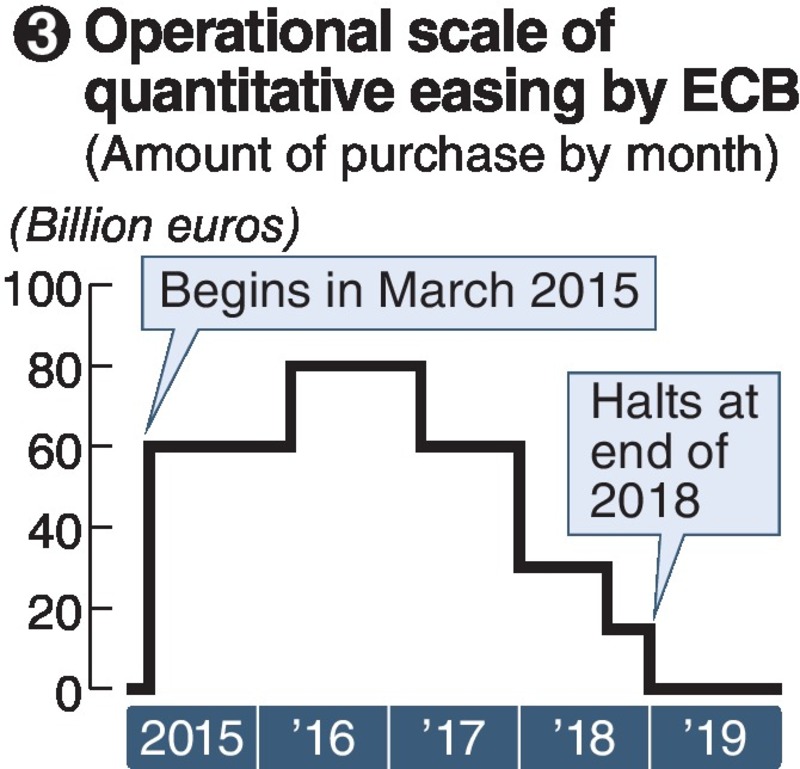

The European Central Bank decided on June 14 to end its quantitative easing program (see below) by the end of 2018 and push ahead with normalization of its monetary policies. Given the economic disparities among nations in the eurozone, the ECB reached a decision for a creative policy that will keep a lid on market turmoil and negative impacts on the economy.

'Local episode'

"We've seen a significant rise in sovereign yields on the back of political uncertainty [in Italy] … Contagion was not significant, if any, if at all, so it was a pretty local episode," ECB President Mario Draghi (see below) said at a press conference after the June 14 regular meeting of the bank's Governing Council that decided to end the quantitative easing program. This marked a major turning point toward normalization of the bank's monetary policies and came on the heels of a similar move by the Federal Reserve Board.

Before the council met, however, some financial market insiders had held a different view: "The ECB won't decide to end the quantitative easing program while political uncertainty is simmering in Italy." This view was prompted by the creation of a populist, anti-EU government in Italy that championed lavish dole-out policies that caused long-term interest rates in that nation to spike.

Observers had pointed out that if the ECB stopped buying government bonds from eurozone nations including Italy, the number of bond buyers would drop, pushing bond prices down sharply and risking a jump in long-term interest rates. In addition, speculation had been swirling that a degree of consideration would be shown to Italy because Draghi is Italian and has experience as governor of the Bank of Italy.

However, Draghi, 70, gave no special treatment to his home country. According to Eurostat, the European Union's statistics office, the eurozone's annual inflation rate in May was 1.9 percent. On the back of the economic recovery, inflation was reaching the ECB's target of "close to 2 percent" and the bank consequently decided its quantitative easing program would not be needed starting in 2019.

The ECB was modeled on the German Bundesbank in its former days, which had a global reputation for being the central bank with the highest level of independence from its government. The ECB puts great emphasis on its independence and does not implement monetary policies that direct attention toward one certain nation.

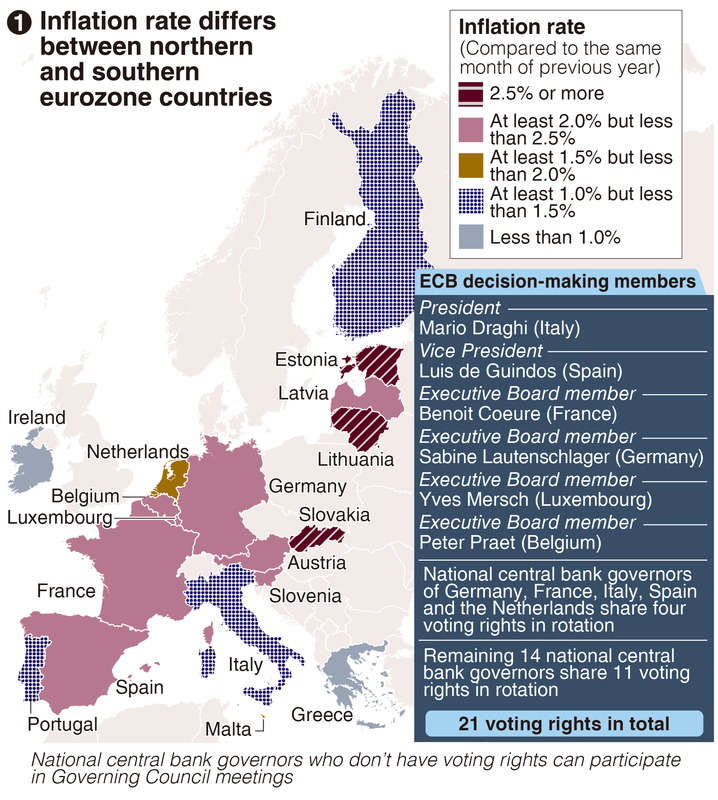

Draghi, ECB Vice President Luis de Guindos of Spain, and four other executive board members from France, Germany, Luxembourg and Belgium are among the 21 members with voting rights at regular meetings of the Governing Council, at which monetary policies are decided. Central bank governors from ECB member states comprise the other voting members. A majority vote is needed to reach a decision.

Disparities among eurozone nations

The ECB has one particular difficulty in policy management that the Bank of Japan, Fed and other central banks do not.

While the ECB implements unified monetary policies for the 19-nation eurozone, it needs to hold the varying inflation rates of its member nations in check and ensure price instability does not roil the entire bloc.

At present, inflation rates vary among eurozone nations (see chart 1). The Baltic nation of Estonia has the highest inflation rate at 3.1 percent, and Germany, France, Belgium and others are among the nations above 2 percent. At the other end of the scale, inflation is hovering around 1 percent in nations including Italy and Greece, which is still feeling the painful effects of a debt crisis.

The differing economic climate between northern nations basking in relatively high growth rates, such as Germany and the Netherlands, and nations in the south struggling to boost their economies, such as Italy, Portugal and Greece, has created what has been dubbed a "north-south divide."

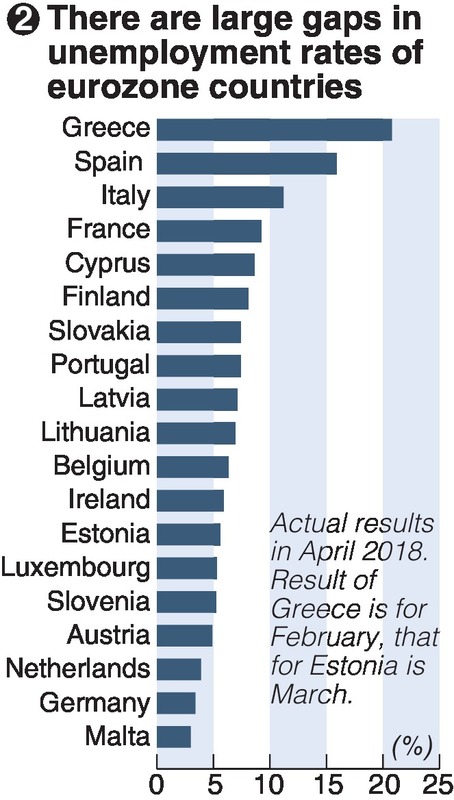

Large differences also are evident in unemployment rates (see chart 2). The highest jobless rate -- above 20 percent, meaning one in five people is out of work -- is in Greece. The rate tops 10 percent in Spain and Italy. By contrast, Germany and the Netherlands have jobless rates of between 3 percent and 4 percent, meaning they almost have full employment.

While participants in the Governing Council operate independently from their nations' governments, there is a strong tendency to advocate for the interests of their home country. Given its current economic climate, Germany does not need a large-scale easing program, so it is prepared to wind up this policy right away. ECB Executive Board member Sabine Lautenschlager, from Germany, has frequently made comments positive about normalizing the bank's financial policies. However, in some southern European nations, monetary easing is still very much needed.

The ECB's decision adroitly dealt with this north-south problem. As well as setting a date for the end of the quantitative easing program, the bank announced it expects key ECB interest rates "to remain at their present levels at least through the summer of 2019." The annual interest rate on money private financial institutions deposit at the ECB is minus 0.4 percent, and this will remain unchanged for at least one year.

"The markets had assumed interest rates could be hiked as soon as the first half of 2019, so the ECB's announcement caught them by surprise and sparked a euro selloff," said Osamu Tanaka, chief economist at Dai-ichi Life Research Institute Inc.

The ECB's quantitative easing program, which started in March 2015 and involved monthly net asset purchases of 60 billion euros, will be reduced to a monthly pace of net purchases of 15 billion euros starting in October (see chart 3). In December, these purchases will end.

Fiscal policy also vital

The ECB has operated without receiving excessive political pressure from individual nations, but it will be difficult to resolve disparities within the eurozone by using monetary policies alone. Delivering stable economic growth requires close coordination on monetary and fiscal policies along with a growth strategy.

Yet, each eurozone nation independently forms its own fiscal policy. Even if European politicians attempt to employ a combination of the ECB's accommodative monetary policies and increased spending to underpin the economy, one problem is that southern nations in bad fiscal shape have little leeway to implement fiscal policies.

European politicians have started the ball rolling on moves to fix this problem.

On June 19, German Chancellor Angela Merkel and French President Emmanuel Macron held talks on the outskirts of Berlin and agreed to work toward introducing a common budget for the single-currency union. This plan aims to rectify disparities with southern European nations in a weak fiscal position, and to enable the provision of flexible support in the event of any future financial crisis.

The ECB was created as one part of the unified Europe pushed forward by a resolve to prevent the continent from being devastated again by war. The bank was established in 1998 under the principle of enabling the free movement of people, goods, capital and services within Europe.

The 19 states making up the eurozone remain under a framework of distinct nations with their own languages and ethnic groups. In Germany, there is strong resentment to German tax revenue being used to fund support for southern nations, so the hurdles to creating a common budget are high. Wisdom and effort will be necessary to incessantly deepen European integration in this regard.

-- Quantitative easing program

A policy that pours money into markets by purchasing large volumes of government and corporate bonds. Described as an unconventional monetary policy, and distinct from monetary policies implemented during normal times to raise or lower policy interest rates in response to economic conditions. The Bank of Japan and the U.S. Federal Reserve Board also have introduced such programs to deal with a financial crisis or lift the economy out of deflation. By pushing interest rates down, these programs are expected to stimulate investment and loans.

-- Mario Draghi

An economist born in Rome, Draghi has been a professor at the University of Florence and vice chairman of U.S. financial giant Goldman Sachs International. After serving as Bank of Italy governor among other posts, Draghi became a prominent figure in international financial circles. Assumed post as European Central Bank president in November 2011 with his term set to expire in October 2019. Noted for his ability to communicate well with the markets, his nicknames include "Super Mario" and the "magician."

Read more from The Japan News at https://japannews.yomiuri.co.jp/