NEW YORK -- It will soon be 10 years since the collapse of major U.S. financial services firm Lehman Brothers in September 2008, which triggered a global financial crisis known as the "Lehman shock." The United States, which was at the center of the crisis, has strengthened financial regulations and expresses confidence in its preventive measures. But has the crisis truly passed?

Remarkable recovery

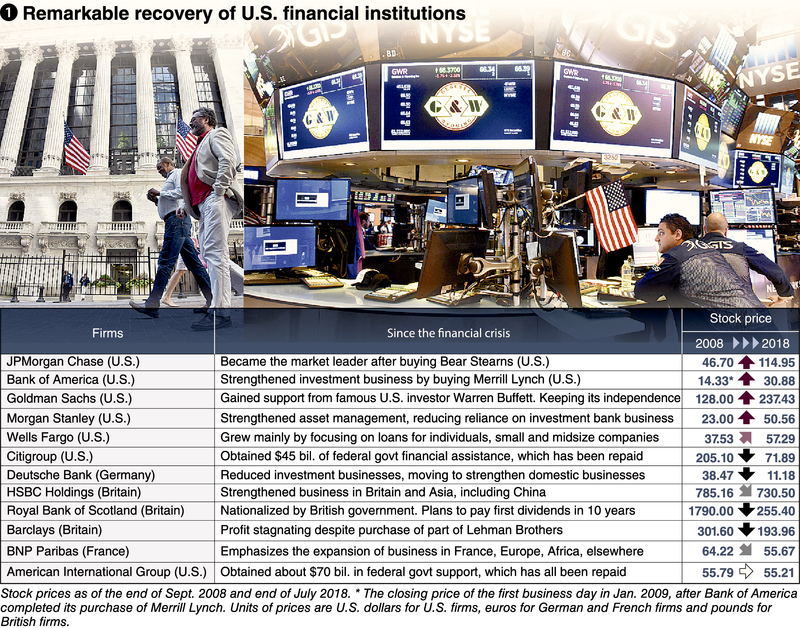

The epicenter of the global crisis was Wall Street in New York. Share prices of major U.S. financial institutions plunged to historic low levels. However, those prices have made remarkable recoveries through improvement of the firms' profits during the expansion of the U.S. economy (see chart 1).

The Federal Reserve Board compiled a report in July in which it concluded, "The U.S. financial system remains substantially more resilient than during the decade before the financial crisis." The Fed has such confidence because all 35 of the companies that were subject to the most recent stress test were able to pass.

Stress tests were introduced in response to the 2008 financial crisis. They verify whether financial institutions can maintain sufficient equity capital even under adverse economic conditions such as a global economic recession.

The latest stress test assumed conditions in which real gross domestic product growth plunges to minus 8.9 percent in 2018 and the unemployment rate worsens to 10 percent in 2019.

In that scenario, losses totalling about 578 billion dollars would be expected for the 35 companies by 2020, but the levels of equity capital of the 35 companies were deemed to be healthy because -- in reality -- they have added a total of about 800 billion dollars in non-debt capital such as common stock since 2009.

Meanwhile, European countries struggled with the 2009 Greek crisis as well as other debt crises and economic stagnation in Italy, Spain and other countries. The disposal of nonperforming loans has been delayed and concern about Europe's financial soundness has not disappeared.

Leverage

A problem revealed by the financial crisis was "systemic risk," in which the bankruptcy of an individual financial institution provokes instability in the entire financial system. A primary factor was trading practices utilizing leverage, in which institutions increased borrowing to expand investment.

Investment banks used leverage to purchase vast quantities of high-risk financial products including subprime loans, which were housing loans targeting low-income borrowers. Repayments fell into arrears due to house prices falling, and the banks received federal assistance.

The U.S. government considered them "too big to fail," and poured vast amounts of tax money into distressed financial institutions. But amid growing criticism of helping "greedy Wall Street" instead of ordinary people, it also put forward stricter regulations.

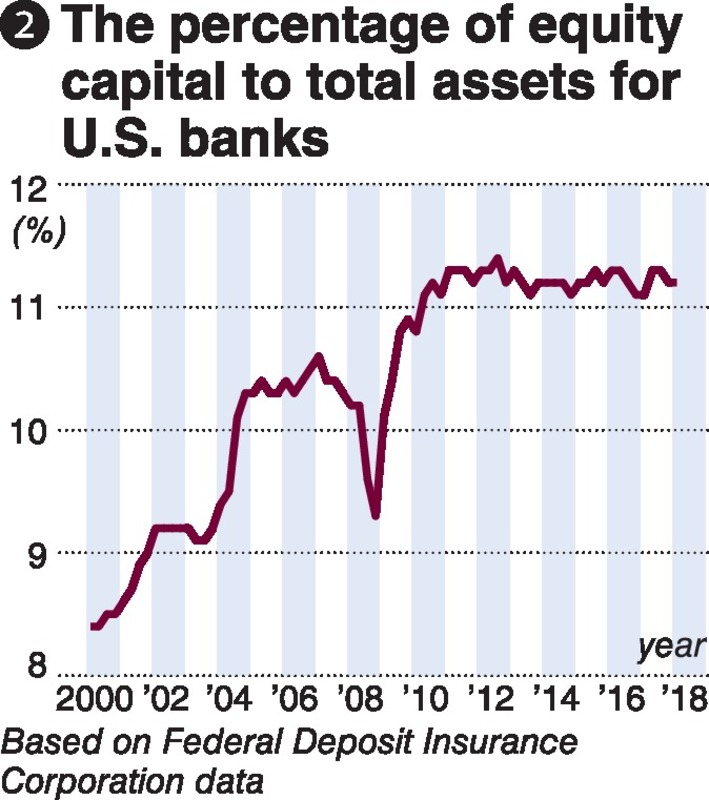

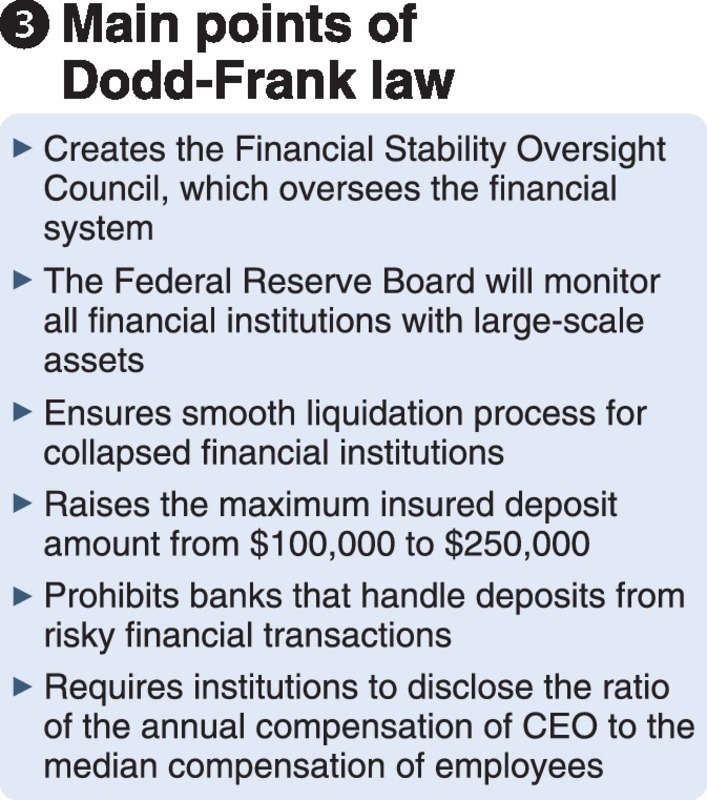

At present, leveraged trading is being held in check (see chart 2). According to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, the ratio of equity capital to total assets for U.S. banks rose from roughly 9 percent at the time of the crisis to more than 11 percent. The results of the Dodd-Frank financial reform law passed under the administration of former U.S. President Barack Obama in 2010 have been significant (see chart 3).

International cooperation ensued as well. In April 2009, the financial regulatory agencies and central banks of major economies founded the Financial Stability Board. It designates important financial institutions to be G-SIFIs (see below), and requires them to hold sufficient equity capital.

Another mainstay of the tougher regulations is the Volcker Rule proposed by former Fed Chairman Paul Volcker. In principle, it prohibits commercial banks that handle deposits from investing in high-risk financial products using their own equity capital.

However, it was hard going to work out the particular rules, such as what sort of transactions should be regarded as speculative and having a high risk. In the face of opposition from financial circles, among other factors, full implementation was postponed to July 2015. There still remain some provisions for which specific regulations have not been established.

A history of contention

The history of U.S. financial regulation goes back to the 1930s. The beginning was the U.S. stock market crash of 1929 and the ensuing Great Depression. It was later discovered that financial institutions had been selling financial products backed by loans with a high risk of insolvency and taking advantage of the crash to sell short.

In response to this, the Glass-Steagall Act was passed in 1933, prohibiting commercial banks from engaging in securities business such as buying and selling stocks. Thereafter, the banks were gradually deregulated, and with the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act passed under the administration of U.S. President Bill Clinton in 1999, they were permitted to engage in both banking and financial services again for the first time in 66 years.

In the United States, there is a perception that this shift invited the 2008 financial crisis. Columbia University Prof. Joseph Stiglitz, a Nobel laureate in economics, said that commercial banks, which are supposed to manage money very conservatively, were taking large risks, and were steeped in a culture of profit-seeking.

Shifting toward deregulation

Even now, U.S. financial institutions persist in a philosophy that values profit above all else. At Wells Fargo in 2016, cases of fraud were discovered in which employees had dishonestly received service fees by opening saving accounts for customers and issuing them credit cards without their permission. The total number of fraud cases reached roughly 3.5 million.

Subsequently, U.S. President Donald Trump, a Republican, signed a bill reforming the Dodd-Frank law this May. The asset threshold for a financial institution to be subject to stress tests was raised from 50 billion dollars to 250 billion dollars.

Looking ahead to the midterm elections in November, the aim is to reduce the burden on small and midsize regional financial institutions and encourage increased lending. It also garnered support from a succession of legislators in the Democratic Party as well. The number of companies subject to stress tests may potentially be cut to around a dozen, and some criticize the revisions as premature.

In response to the change of government when Trump took office, lobbying expenditures of banks in 2017 were at their highest level since 1998, while lobbying by the securities and investment industry increased for the first time in seven years.

"I think Dodd-Frank was the right thing to do at the time -- in the very unstable wake of a very big financial crisis," Duke University Prof. Lawrence Baxter said. "It was important to psychologically calm down the financial markets. Long term, Dodd-Frank needs a fairly substantial overhaul."

European financial institutions are also grappling with uncertainty. Deutsche Bank ran at a total net loss for three consecutive years through 2017, and for a time, the market swirled with rumors of financial instability. In Italy, the major bank Banca Monte dei Paschi di Siena was nationalized in 2017 due to problems with nonperforming loans.

What history demonstrates is the difficulty of appropriately picking out the risks lurking in financial markets. This has not changed even now, 10 years after the financial crisis.

-- G-SIFIs

Global Systemically Important Financial Institutions. They have been selected since 2011 by the Financial Stability Board, composed of financial supervisory agencies and other organizations of major economies. Insurance companies were added to banks in 2013. Japanese institutions include Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group, Mizuho Financial Group and Sumitomo Mitsui Financial Group.

Read more from The Japan News at https://japannews.yomiuri.co.jp/