After Hotel California, the Eagles’ landmark 1976 album, saw them rise from country rockers to just plain rockers, Don Felder and his bandmates should have been on top of the world – but all was not well in paradise.

The warm smell of colitas was not rising up through the air, and there was a distinct lack of cool wind in the band’s collective hair. Exhaustion, infighting, drugs and alcohol – basically the tropes that were supposed to drag down rock bands, as per Cameron Crowe’s Almost Famous – had all but derailed the Eagles.

After the supporting tour for Hotel California, they could have stopped – and they should have stopped… for the night (okay, that’s my last Hotel California reference) – but they didn’t. Instead, they hit the first of what would be five studios in 18 months and kicked off the sessions for the aptly titled The Long Run.

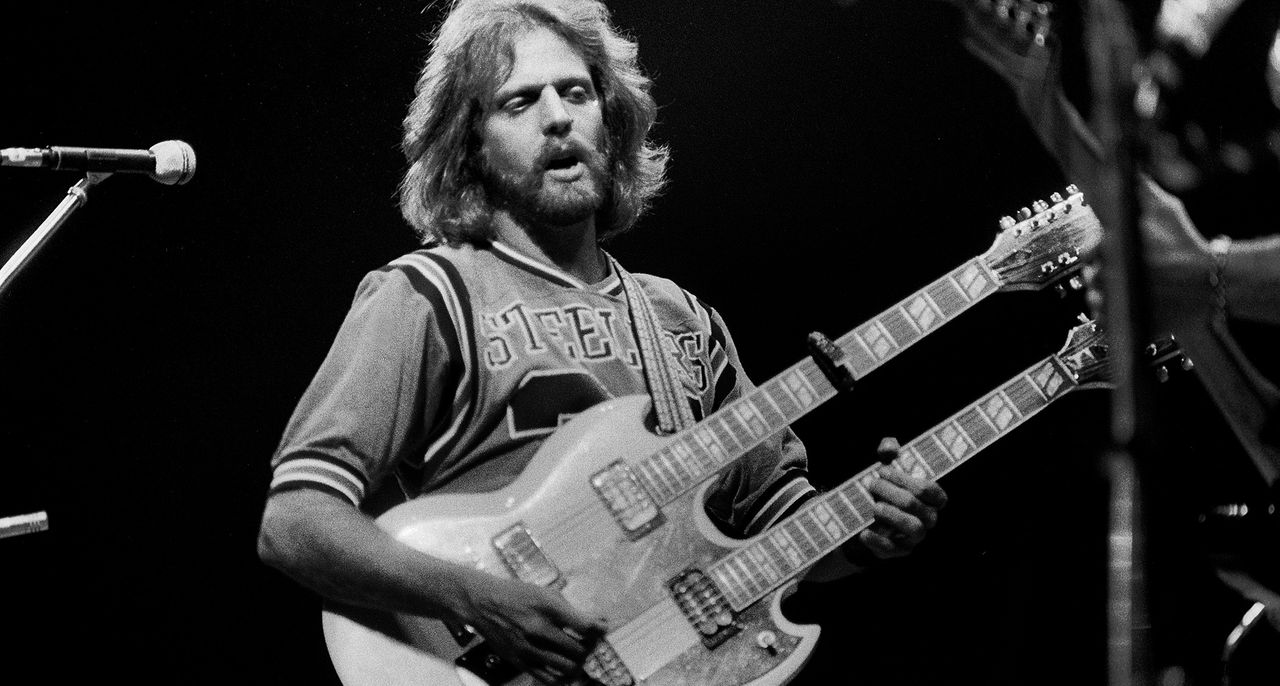

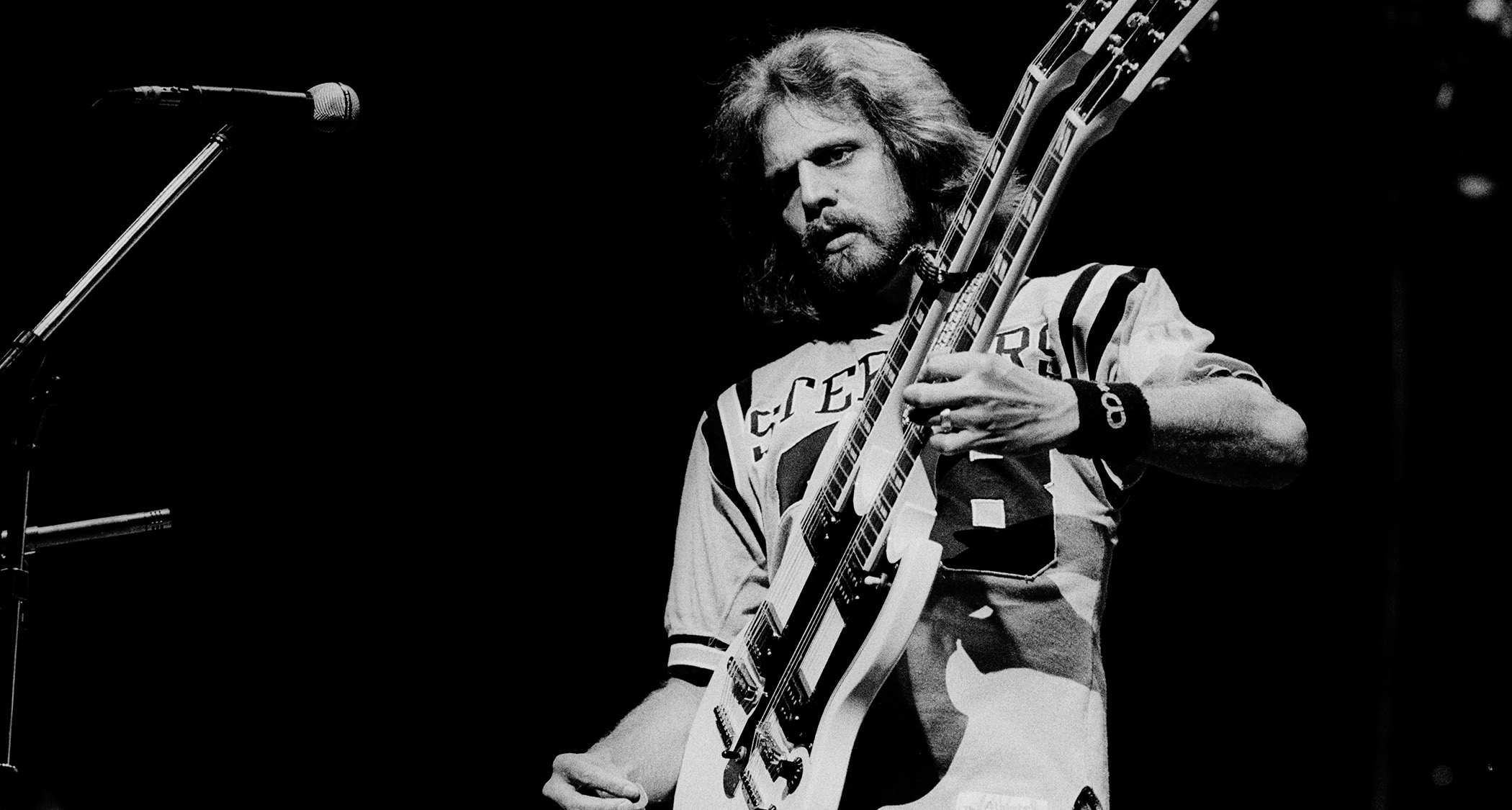

Don Felder, one of the classic Eagles lineup’s trio of guitarists alongside Glenn Frey and Joe Walsh, remembers this period well. “The Long Run was a kind of crazy album,” he says. “We started without very many song ideas.”

Given the sheer strength of Hotel California, it’s strange to think the Eagles suffered from a lack of songs, but it’s true.

“Joe had joined during the Hotel California album,” Felder says. “When we got to The Long Run, we were right off the road, going into the studio, and nobody had a break or time to start writing. It was a difficult time personally, physically, emotionally and creatively in every way.”

On the surface, The Long Run doesn’t seem too far off from Hotel California. But Felder refers to The Long Run sessions as a dark time, adding, “If you look at it, that’s why the record is black. And when you opened it up, the photo of us was dark.”

To Felder’s point, if you dig deeper into The Long Run, themes of darkness linger. Be it The Disco Stranger, with its overt disdain for four-on-the-floor beats, or the bewilderment of I Can’t Tell You Why, The Long Run is a snapshot of a band on the brink of self-destruction. But it wasn’t all bad, as Felder and Walsh traded off plenty of quintessential riffs and solos.

“Joe and I always had a great personal relationship and a great deal of respect for each other,” Felder says. “We developed, without even talking about it, the ability to dance together, where somebody would take a step back and support the person who stepped forward, and that person would step back and support the other person to step forward.”

After a year and a half of self-inflicted damage, The Long Run hit shelves in September 1979. Although not as lauded as Hotel California, The Long Run eventually sold in the millions, giving the Eagles a proper followup.

Still, critics weren’t initially kind to The Long Run, likely as a market correction for lavishing so much praise on Hotel California. But no shade thrown the Eagles’ way could do more damage than the wounds already inflicted, and by 1980, the Eagles had imploded.

Darkness, sadness and an eventual public breakup will always be inextricably linked to The Long Run. But like most things in life, there are two sides to every story, and with separation, Felder can see some positives.

“We made the absolute best product we could,” he says. “Fortunately, it’s kind of stood the test of time. Even though it took a long time to produce, I think it was well worth the effort, the energy and not letting stuff slide by that really shouldn’t be on the record.”

Did the Eagles feel pressure to follow up Hotel California with a great album?

“I think Glenn [Frey] said it best when he said we “created a monster with Hotel California, and it ate us.” We were trying to get back up over the bar because we had raised the bar every album with the songwriting, performance, vocals and guitars; it was more and more refined toward being spotlessly perfect.”

Notoriously, The Long Run took 18 months to record – in five different studios! That had to be draining.

“Bernie [Leadon] had left the band during the very end of the One of These Nights album [1975] because he kept saying, ‘We need to take a break. We just needed to take three weeks or a month off, stop doing it, go to Hawaii, get some rest, get off drugs and drinking and just recharge ourselves, and then regroup.’ Nobody wanted to do that.”

Why not?

“Everybody kept saying, ‘We’re pushing this uphill, we’ve got to keep going.’ [Bernie’s advice] was probably the most sound advice anybody gave that band, and it was only upon his departure that I realized how right he was. The longer we stayed at that pace, the more difficult it became to be happy, in a good mood, have fun and write great songs. It was just very heavy to continue on.”

Despite the heaviness and darkness surrounding the band, The Long Run boasts several great songs, including Those Shoes, which features you and Joe on dueling talk boxes.

“I wanted to do some unique stuff with Joe, so I wrote the music for what became Those Shoes. I wanted to do two talk boxes, like two trumpets that would play that line. So Joe and I played harmony talk boxes, and we had a place for a talk box solo, which had never existed on any of the Eagles’ records. It was a new sound in those days.”

You also wrote the music for one of the more rocking tracks on the record, The Disco Strangler.

“I wrote the song that Don Henley started writing lyrics to called The Disco Strangler. It was back in the disco days, and [Don] hated disco. [Laughs] He hates the four-on-the-floor beats; he just wanted to kill disco, you know? So he took this little music track I had written and he wrote [the lyrics for] The Disco Strangler.”

It’s it true that your solo song Heavy Metal originated from The Long Run sessions?

“I wanted to do a follow-up to Hotel, where Joe and I could play off each other, much like we do in Hotel. We recorded a basic track tentatively titled You’re Really High, Aren’t You? but we didn’t have lyrics, and I was just writing the music. It was much heavier, sort of toward the heavy metal edge, but it would have been more refined, like Hotel was, but with a harder rock edge. We loved it.”

If you loved it, why didn’t that track end up on The Long Run?

“We ran out of the time we had allocated to finish the album. We had a tour starting, so there’s a track that was written by me and played live by the Eagles, but it never got finished. So when I got a call from a movie director to come to the studio and write songs for this crazy animated movie called Heavy Metal [1981], I thought of the track and said, ‘Maybe I could take the idea musically and turn it into something for this movie,’ because it was never going to happen with the Eagles at that point. So I did.”

How did you, Glenn and Joe divide the guitar parts on the rest of The Long Run?

We never played three Gibsons – it was always a Strat, a Tele and a Les Paul, or a Gretsch, just to have tonal separation

“A lot of that just kind of fell into place as things happened. It really fell into what was needed for each song and who was going to play what. We never played three Gibsons; it was always a Strat, a Tele and a Les Paul, or a Gretsch, just to have tonal separation. You could recognize one player because his sound was so different from the others.

“I remember Joe came into the studio one day with this old Strat. He brought it in, plugged it in and was sitting there playing, and I said, ‘That thing sounds great. Let me hear that,’ and I picked it up, and it sounded like me. [Laughs] It didn’t sound like Joe. So we just kind of figured out, ‘Okay, who’s gonna play what?’”

As far as lead guitar goes, how would you describe the yin and yang between you and Joe while recording The Long Run?

“As we were soloing together, he would go up and be playing high and I’d be playing a solo underneath him halftime, and he would be playing faster, and I’d be playing low and slow. Then he would start coming down, so I’d start going up, and he’d be playing low and slow and I’d be playing fast and high.

“It was a dance we worked out without ever having talked about it. It was just a natural way we figured out how to play together, sense each other and respect each other.”

Despite it being a long process during a dark period, did you feel good about The Long Run the first time you listened back to it?

“I thought we had done a really good job with what he had. We had people with casts and wounds and crutches to get through the very few last months of finishing that record. But when you listen to it, you don’t hear any of that. It just came across really great. I was happy that we had done it, you know, put a bow on it and put it out.”

Do you look back on The Long Run fondly now that you’ve had some separation?

“Yeah. I think the combination of all the players I was in the band with, like Bernie and then Joe, and Randy Meisner and then Timothy [B. Schmit], who joined to replace Randy, the music and the writing were of a really high quality.

“We just kept setting the bar higher and higher and higher in songwriting, lyrics, vocals and guitar parts and in the way the band sounded and the way it was recorded.”

- The Long Run is out now via Elektra.

- This article first appeared in Guitar World. Subscribe and save.