In Spain, far-right parties such as Vox have reiterated their allegiance to the dictator Francisco Franco, who died 50 years ago on 20 November, 1975. In a bid to counterbalance this, the country's leftist government has announced hundreds of events throughout the year to mark the restoration of democracy.

The government on Wednesday announced a series of 480 concerts, conferences and exhibitions under the slogan "Spain at Liberty", celebrating the restoration of democracy after the death of General Franco, who died in 1975 aged 82 after ruling Spain with an iron fist for nearly four decades.

Democratic elections followed in 1977 and newly enfranchised Spaniards approved a new constitution in a referendum the following year, now celebrated with a public holiday on 6 December.

Spain's Democratic Memory Minister Angel Victor Torres said that instead of holding an event on the anniversary of Franco's death on Thursday, the government had opted for "celebrating the recovery of democracy" throughout the year.

"We are not celebrating the death of the dictator, we are celebrating the beginning of the end [of the dictatorship]", he told a news conference.

More than 150 events have already been held so far this year across the country, and Torres said the programme would be extended into 2026 and possibly beyond.

He added that many of the events would focus on people born after the end of the dictatorship who did not experience the "years without freedom".

International discourse

Spain continues to grapple with Franco's legacy and the scars left by one of Europe's bloodiest fascist regimes.

Franco rose to power during the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) on the back of a coup against the country's left-wing Republican government.

Under his authoritarian regime, the country experienced censorship, repression of minorities, totalitarian indoctrination and the execution of dissidents.

Historian François Godicheau told RFI that Francosim was able to stand the test of time because it adapted quickly to the post-war world.

"It adapted to the Cold War. It became the champion of anti-Communism," he said.

Godicheau says the same discourse can be heard today at an international level.

"Today, the same thing is happening in the rhetoric of Vox as in the rhetoric of President Javier Milei in Argentina, for example. Anything that vaguely resembles a redistributive policy... is Communism."

Over recent years, Madrid has hosted far-right leaders from Europe and beyond, thanks to invitations from the leader of the Vox party, Santiago Abascal – including France's Marine Le Pen, Hungary's Viktor Orban, Italy's Matteo Salvini, Geert Wilders from the Netherlands, and Milei.

Adapting United States President Donald Trump's "Make America Great Again" to "Make Europe great again", Abascal, as head of the Patriots for Europe parliamentary group, hosted the Patriots for Europe summit in Madrid on 8 February this year.

At the podium, Orban paid tribute to the "role of Francoist Spain" which rid the country of Communists, while Wilders praised the Reconquista, which expelled Muslims from Europe.

For Godicheau, however, the biggest legacy of Francoism is "political apathy" – Franco having famously said: "I don't do politics."

From Washington to Warsaw: how MAGA influence is reshaping Europe’s far right

A new generation

In the 1960s, Franco's regime presented itself as the guarantor of a form of peace and internal stability, rooted in the population's need to heal the wounds of war, repression, hunger and poverty, and in the fear of a new conflict.

In the mid-1970s, after his death, the transition unfolded rapidly: elections, political reform, the dissolution of pro-Franco groups, the amnesty law of 1977 and then the monarchical Constitution of October 1978.

But there remained pockets of resistance, with some far-right groups organising street demonstrations on symbolic dates from Franco's rule, which drew thousands of people.

In October 1976, the Popular Alliance emerged, founded by former Francoist officials. It would later become the current Popular Party (PP).

Its platform was conservative and populist: order, security, support for the monarchy and constitutional reforms. It also embraced aspects of the Francoist legacy, including Catholicism and a market economy.

Several factors explain the re-emergence of these right-wing voices, including PP and Vox, at the beginning of the 21st century. Besides the country's economic and social challenges, a new generation of Spanish political leaders has been emboldened by the rise of far-right movements across Europe.

The Nazi roots of today's global far-right movements

Legal framework

Spain has since the 1970s grappled with a legal framework to address the crimes committed under Franco's rule.

The 2007 "Law for the Recovery of Historical Memory" removed references to Francoism from the public sphere and encouraged academic and grassroots research on the repression up to the dictator's death.

It refers to "victims" but without naming any perpetrators, reflecting the spirit of reconciliation inherent in the democratic transition.

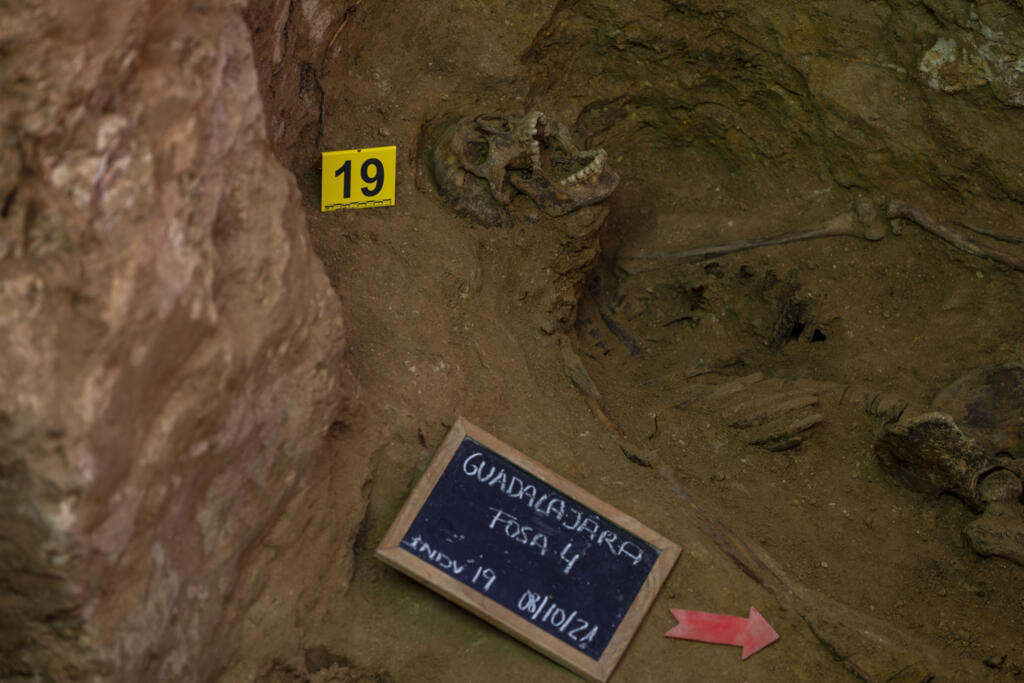

In October 2022, the "Democratic Memory Law", introduced by the government of Pedro Sanchez, replaced the previous legislation, addressing its shortcomings. Forced disappearances and mass graves were among the areas not covered by the previous law.

Several regions governed by PP-Vox coalitions have responded by proposing so-called "concord laws" intended to repeal the main provisions of the Democratic Memory Law.

A reformed curriculum

To challenge the narrative reinforced by educational programmes under Franco, the Spanish government revised the country's history and geography curriculum in November 2024.

Lessons on the Civil War now include repression, exile and resistance, while those on the democratic transition also address remembrance and reparations.

But Vox-PP coalitions are putting in place their own educational agendas. In Andalusia, the governing coalition has demanded the removal of certain books from schools on the grounds that they contribute to the indoctrination of children.

Eye on France: A dark chapter of Franco-Spanish history

These movements are also vehemently opposed to the recent decision by Sanchez's government to remove symbols that recall the military dictatorship, its atrocities and its leaders from public spaces.

Among the examples are the Valley of the Fallen, the shrine to Nationalist soldiers, and the legal battle over the exhumation of Franco's remains in October 2019.

These memorial sites have become ideological battlegrounds, which the right and far right accuse Sanchez's government of exploiting in order to consolidate the ranks of a fragile majority.

The government has also initiated a process to ban foundations such as the Francisco Franco Foundation, the José Antonio Primo de Rivera Foundation and the Serrano Suñer Foundation, whose purpose is to perpetuate the memory of the regime's ideologues.

A siege narrative

To exert more influence at the ballot box, pressure groups have sprung up working to bring Vox, the PP and the centre-right Ciudadanos closer together.

Historian Godicheau says these convergences are possible because these movements share common values and demands, notably around immigration.

"If Vox and its ilk claim a number of characteristic features of Francoism using Francoist rhetoric, it’s because there’s a potential political benefit. Namely, it’s possible to get people to identify with a narrative of a nation under siege...a glorious, pure Spain surrounded by enemies within."

This culture has permeated the country for several decades, shaping Spaniards over several generations, Godicheau said. "It’s easier to reactivate it than it would be in France to fully embrace Vichy, the militia, and the Vel’ d’Hiv roundup."

Paris honours the forgotten Spanish fighters who liberated the French capital

According to an October survey by Spain's national polling institute CIS, around 20 percent of Spaniards thought Franco's dictatorship was "good" or "very good", with 65.5 percent describing it as "bad" or "very bad".

As the country marks the 50th anniversary of Franco's death, Francoism itself clearly has not been laid to rest.

During the massive power outage that paralysed the country in April, Luis Felipe Utrera-Molina, the lawyer for the heirs of the former dictator Franco, posted on the social network X (formerly Twitter): "Under Franco, this didn’t happen."

The message was "liked" more than a thousand times.

This article has been adapted from the original version in French by Isabelle Le Gonidec.