On the drive home for Thanksgiving, a wave of familiar feelings confronted me.

As I crossed the bridge over the St. Croix River from Wisconsin into Minnesota, there was the tug-of-war between excitement and nerves as I reminisced on holidays past — some lovely, others tinged with tension, arguments or grief.

And then there was another familiar feeling: I was sporting a new tattoo that my parents didn’t know about yet.

I’d been here before, four times in fact. And each time I’d handled the situation a little differently. Seven years ago, at age 19, just before I first marked my body with a symbol of a sword etched into a fountain-tip pen, a nod to the adage “the pen is mightier than the sword,” I did what I thought was best and warned both parents.

My mom was gutted, reacting like I told her I had a terminal illness or was being shipped off to war. She hugged me for a long time at the door, tears brimming her eyes, and desperately pleaded: “Why are you doing this to me?”

My dad offered me $200 not to get the tattoo.

I did it anyway, and we never talked about it again.

Until four years later, when I again laid down on a tattoo artist’s table in South Carolina, where I lived for two years between stints in Chicago. A map of the Great Lakes decorated my ribcage, cementing my status as a Midwesterner temporarily displaced in the South.

This time, I waited until the ink was sitting beneath my skin to tell my parents. I naively thought they might be honored, maybe even a little excited, since part of my awe of the Great Lakes stems from their commitment to raising my siblings and me with a strong appreciation of the best waters in the world. Trips to Michigan’s Upper Peninsula and Minnesota’s North Shore, and plunges into their frigid waters, marked my childhood just as much as the Harry Potter books and learning how to ski.

It didn’t make a big difference. They were still upset.

But with my third tattoo, something shifted. I had long been sitting on the idea of the redwood tree pines as a tattoo; I even had the specific sprig.

One had been taped into a card sent by my Uncle Jim when I was 8. When he died suddenly in 2019, grief dominated my life, governing every thought, emotion and decision for what felt like way too long.

The grief still hits me every once in a while. But even though once-fond memories of diving into the waves off of Molokai, Hawaii, or conversations about media and technology are now tainted by his absence, I have a permanent reminder of UJ, as we call him, and the lessons I learned from him right there on my arm.

So much of me is made from what I learned from him, as Elphaba and Glinda sing in “Wicked,” the first Broadway musical I ever saw, thanks to UJ’s generosity and love for New York City theater.

And UJ had his own appreciation of unconventional gestures. I think he’d be OK with a tattoo in his memory.

A new tattoo, a new approach.

I texted my mom a photo of the tattoo and a photo of the card, now framed on my desk.

My mom texted back, “Is that on your arm?”

I had no idea what to make of that. I figured she wasn’t thrilled, perhaps a little offended that I chose to honor her brother in a way that I knew she’d frown upon.

But the next time I saw her, my brother complimented the ink, and my eyes darted toward my mom expecting at least a slight bit of vitriol.

“I’m fine with it,” she said.

Now, here’s the thing about my mom. She has strong opinions that are unlikely to change, especially about things that could be deemed superficial. She cares a lot about the way people spell their names, for example. She loathes the color purple. And she cares a lot about tattoos.

So when she said she was “fine” with a noticeable tattoo on her daughter’s body, that was a huge win for me.

Not only because I wanted to win, but because it seemed she finally grasped that tattoos are my form of self-expression that she may not agree with, but she can maybe start to understand.

She knows how much I loved UJ. I know how much she loved him, too. Somehow, without saying it out loud, we seemed to communicate that to each other and share a sliver of grief and love through a tattoo, a few texts and a resounding “I’m fine with it.”

So the next time I came home with a new tattoo, some of the pressure was off. Without much ceremony or premature defensiveness, I showed her the new sketch of a few flowers on my ankle. This one doesn’t have much meaning; I just think it’s cute. Like many tattooed people, I’ve become less attached to the tattoos’ significance, and I’m more into the artistry.

And finally, the admittance I’d been waiting for: “I think I’ve kind of changed my tune on tattoos.”

You see, since the last time I revealed new ink to my parents, I had started writing for the Sun-Times “Inking Well” series about body art, and I’d gotten to interview some pretty cool people with pretty cool stories.

My mom loved them. In place of the typical violent and tragic stories I send her to showcase my work, she welcomed the lighthearted anecdotes of my interviewees, from a Bucktown resident who loved his family heirloom bike so much he had it tattooed on him, to the Orland Park bride who complemented her wedding dress with a huge statement piece on her back.

My parents and I often have trouble understanding each other. But this saga of expanding my collection of body art has allowed us to ease into the other’s perspective just a little bit.

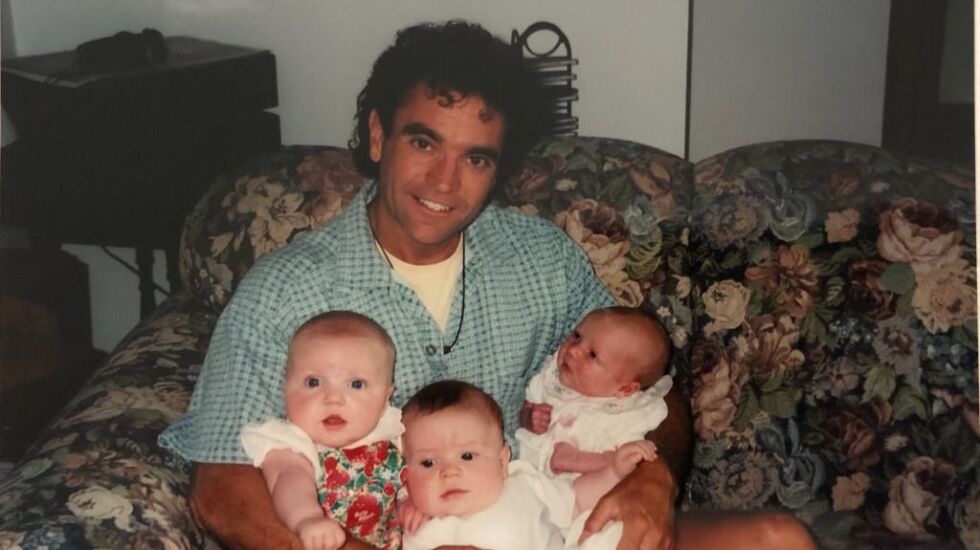

Whether or not they believe me when I say this, I do understand where they’re coming from. I look at my niece and nephew, so young and perfect, and think “How could anyone possibly mark up these arms, these legs?” And I remember that I was once a baby, too, and that’s probably the version of me that pops into their heads when I announce I went under the tattoo needle once again.

They’ve also come a long way in accepting that these decisions are mine to make, not theirs. Again, whether they believe me or not, I really do appreciate it.

So this Thanksgiving, when I rolled up the sleeve of my well-worn, ratty sweatshirt to reveal twin strawberries sitting just above my elbow, I was still on the receiving end of an eye roll from my mom. But it felt a little bit less judgmental and harsh. It felt like it had just a little more love and levity behind it than it once did.

I know I’m not the only one with a similar story. Tattoos and our parents’ reactions to them are often a topic of conversation among my Millennial and Gen Z friends. We all get a kick out of it.

Tattoos are growing more popular among younger generations, and people are more likely to have multiple tattoos, according to a Pew Research Center study published in August. Around 41% of people ages 18-29, my age group, reported having a tattoo, compared to my parents’ age reporting only 25% for people ages 50-64.

When I broached the topic of writing a piece about my tattoos and her reactions to them for Sun-Times readers to read, my mom had some concerns. Most of all: “Ugh ... you’re going to make me sound so old.”

I probably will make her sound old. But that’s the whole point.

Maybe things like tattoos, including pronouns in an email signature and spending too much time and money on a bachelorette party are just my generation’s version of rock concerts and smoking weed — pretty harmless forms of bucking the status quo of the generation that came before us, shaking up the norm to make the world look a little more like we want it to.

When my niece and nephew grow older, I’m sure I’ll look at some things they’re doing and roll my eyes or ask semi-accusatory questions. After all, the only certainties in life are death and judging the generation that comes after you.

But then I’ll take them to get their first tattoos, perhaps against their mother’s wishes (sorry, Emily) and remember being young and learning how to make decisions on my own.

I hope, somewhere deep down, that’s what my parents think about me, too.

._Patrick_s_Day_Parade_94380.jpg?w=600)