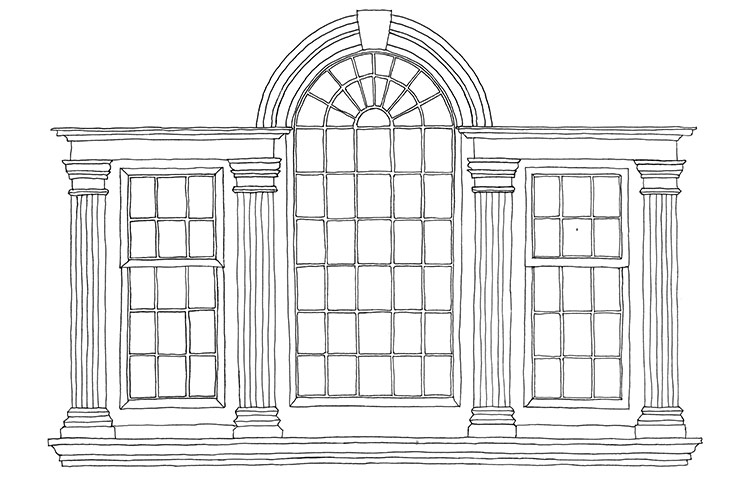

Also called a “Venetian window” or a “serliana”, this was an essential ingredient for most neoclassical buildings. A window in three parts, with the central light rising taller to be rounded off in an arch and the two side lights flanked by pilasters and crowned by entablatures. Smooth, smart and satisfyingly symmetrical.

Illustration: Emma Kelly

An introduction of the late 18th century, this form of roof has four sloping sides, each of which becomes much steeper midway down. These were tall and spacious, and allowed owners of buildings to sneakily gain an extra floor without really looking like they’d done so. They were first popularised by French architect François Mansart in the baroque period and are also referred to as a French roof.

Illustration: Emma Kelly

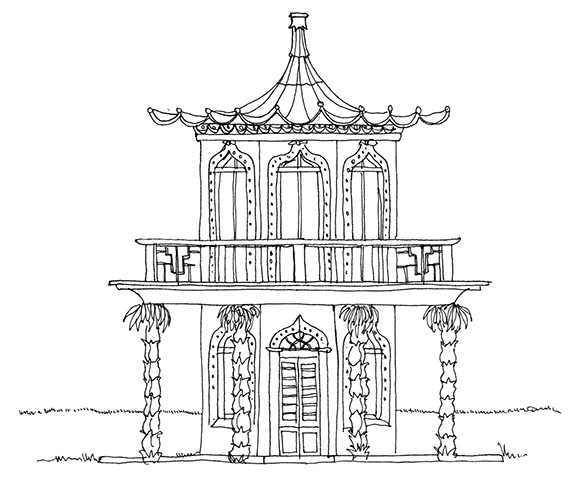

From the late 17th century, when China relaxed its foreign trade restrictions, Chinese fabrics and ceramics began to be seen in increasing quantities in the west. Soon every self-respecting household had a Chinese room, replete with decorative painted wallpapers, tiles, rugs and furnishings. The trend reached buildings some 50 years later in a filtered, exaggerated way, with results that bore little resemblance to anything you might actually see in China. Key characteristics included curling upturned eaves on roofs, lacquered or gilded mouldings, bas-reliefs and motifs such as dragons, birds, exotic flowers and figures in oriental dress.

Illustration: Emma Kelly

This is the white render applied to late-Georgian facades that could also be sculpted and moulded for decorative purposes. It was a kind of weather-resistant plaster, traditionally made of lime and sand with the addition of fibres – plant or animal.

Illustration: Emma Kelly

This clever trick arrived in Britain from the Netherlands during the late 17th century. It allowed master bricklayers to visually correct the many imperfections of the handmade bricks they were working with. First a brick-coloured mortar is used to even out the ragged edges of the brick and then a projecting mortar (usually neutral or cream-coloured) is applied in thin straight lines, which creates the impression of uniform brickwork.

Illustration: Emma Kelly

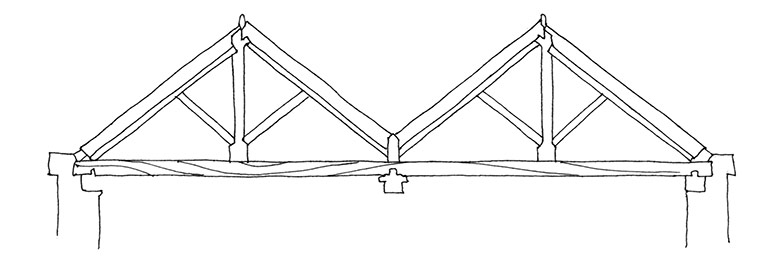

To allow a deeper breadth of building, designers continued to employ the M-shaped or valley roof first used in the previous baroque period. These were two adjacent pitched roofs, allowing the building to be at least two rooms deep, with a central gutter. But the Georgians’ love of the classical form led to a flatter version, often hidden from view behind a parapet.

Illustration: Emma Kelly

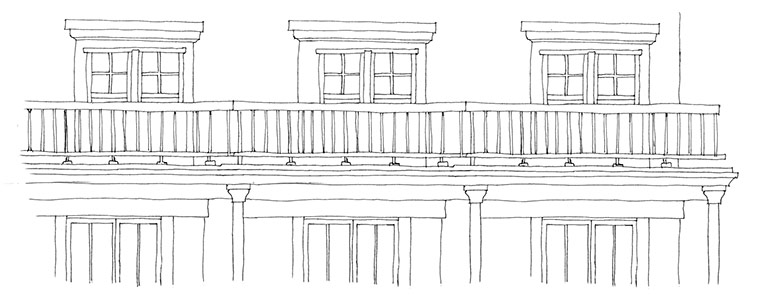

Classical designers wanted to detach themselves from the steep, pitched roofs that were typical of earlier centuries. Hiding a roof was one good step forward in this direction. Houses were instead crowned with straight fringes – a horizontal, roof-line balustrade or coping to the top of the facade that echoed the rooflines of buildings from the ancient world.

Illustration: Emma Kelly

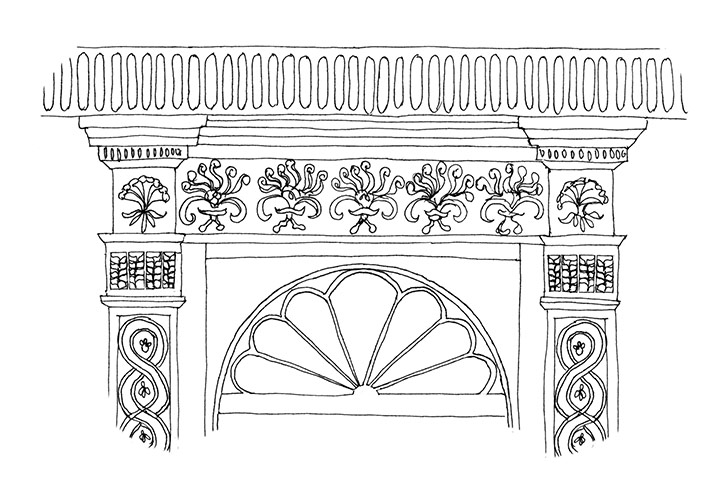

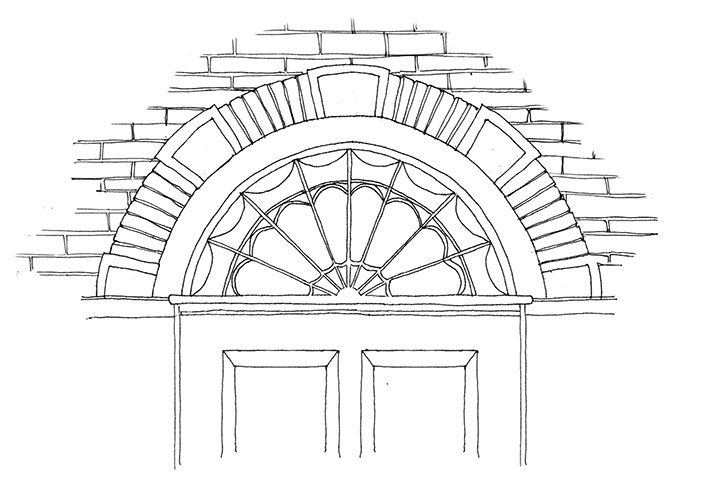

Also known as a sunburst light, this is the arched window found above a Georgian door, with panes of glass separated by tracery radiating out in segments like a fan.

Illustration: Emma Kelly

Georgian architecture favoured the symmetry of paired chimneys, one on each end wall. This enabled them to have fireplaces in almost every room. Coal now largely replaced wood.

Illustration: Emma Kelly

A row of columns supporting an entablature, and sometimes a pediment too, were often used to link the facades of a number of adjoining houses, or even an entire terrace.

Illustration: Emma Kelly