Momentum is building for a truly national ban on a popular yabby trap which drowns any air-breathing animal that can fit inside it, including the vulnerable platypus.

So-called opera house traps are a collapsible net with a funnel-shaped entry on each side.

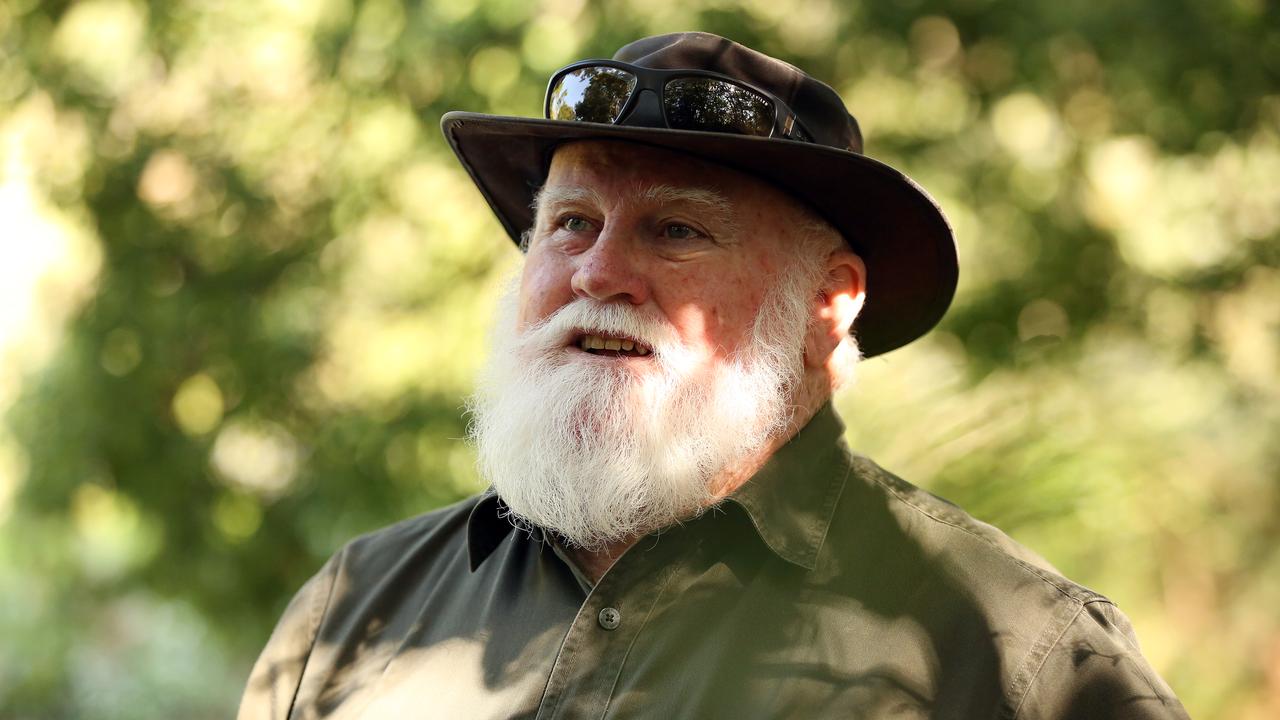

Neil Andison, who works as a platypus guide in Maleny on the Sunshine Coast hinterland, has spent a decade writing to politicians across Queensland in an attempt to highlight the urgency of the issue.

And he says it's not just platypus that become bycatch.

"They're a death trap," he says of the traps.

"Anything that breathes air that gets caught in them can't get out."

That includes the rakali, also known as the water rat. So too turtles, other reptiles such as water dragons and even waterbirds like cormorants.

For this reason, opera house traps are banned or restricted in every Australian state and territory, including Western Australia and the Northern Territory, where there are no platypus. Queensland is an outlier.

Platypus are a tourist attraction in Maleny and a prominent part of the local iconography, including the local pub, where it features on signage, staff polos and even beer coasters.

They are often seen in the middle of town along the Obi Obi Creek, including next to a Woolworths which was the subject of local protests before it was built 20 years ago.

Occasionally, Mr Andison finds discarded or unattended opera house traps in the creek.

When he does, they end up in the rubbish.

When swimming underwater, a platypus is effectively blind. They find their food - small crustaceans (including yabbies) via their distinctive duck-like bill, which is filled with tens of thousands of electrical receptors.

The movement created by a yabby in an opera house trap emits electrical pulses, which attracts the platypus - which can hold its breath for about three minutes under water.

Unable to escape the trap after it enters the funnel, the platypus drowns.

In worst-case scenarios, the situation compounds. As the platypus rots, more yabbies come to the trap to gnaw on the carcass which, in turn, attracts more platypus.

In Labertouche Creek, east of Melbourne, five platypus were found drowned in two traps in 2017. The nets were subsequently banned from sale in the state in 2019.

The platypus is regarded as near threatened according to the IUCN Red List. A report in 2020 recommended that it be upgraded to threatened status nationally, with numbers declining in all states where it occurs.

But it's not known exactly what toll opera house traps take on platypus populations.

A study by the CSIRO suggested up to 30 had died in Victoria leading up to the ban in 2019 but that only reflected those that could be found.

Tamielle Brunt, senior platypus project officer with Wildlife Queensland, says the reason for the knowledge gap is simple.

"Most people don't want to admit that they've drowned anything other than yabbies in those nets," she says.

Queensland Environment Minister Andrew Powell is the member for Glass House Mountains, with an electorate office in Maleny. Both Mr Andison and Dr Brunt say they have written to him repeatedly.

"In my capacity as the local member for Glass House, I am very conscious of the concerns around the use of opera traps," Mr Powell says in a statement issued to AAP.

He says he has discussed the issue with the state's minister for primary industries, Tony Perrett, and that the Queensland government released a consultation report in March by the Freshwater Working Group.

The document shows 65 per cent of respondents to a survey in favour of a ban on opera house traps, with 35 per cent of them supporting an immediate ban.

A further 30 per cent favour a phase-out, with a ban taking effect from mid-2025.

But that time has already passed.

Mr Perrett's office says the results "will be further considered for future decision-making on these management arrangements" and that once a review is complete, there will be further consultation between the ministers and stakeholders.

No new timeline for the discussions has been offered.

Mr Andison says it follows a pattern set by the previous Labor government, where the issue was handballed between the two departments.

"They bounced it back and forth saying, 'it's not mine, it's his', as they are wont to do," he adds.

"So I just pursued that as best I could and then we had a change of government."

Dr Brunt says that change likely held up the process.

"There's just never been someone who's taken the initiative to put their foot down and say enough is enough," she says.

"Over 65 per cent of people who engaged with that survey said they supported a complete ban, right then and there, or a phase-out.

"What's the point of having that survey if they're not going to take that information and actually move on it?"