Tim Grandage arrived in Calcutta from Hong Kong in 1987 to begin a two-year posting as manager of a local branch of the Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation (HSBC). Each day when he parked his car around the corner from the bank, he was distressed to see a group of street children eking out a living from other people’s leftovers.

“One night when I went to pick up the car, the children crowded around me, all speaking at once,” Grandage says. “I didn’t understand much but knew they were worried it would get stolen and they would be blamed by the police.”

Grandage let the children sleep inside, under or on the car if they protected it from thieves. As his friendship with them grew, he became determined to do something for them. Before long he had turned his apartment into a home for 35 children sleeping safely on the floor and eating three regular meals a day.

“I realised then that I was committed to the children,” says Grandage, who set up a non-profit organisation called Future Hope in 1987. “I named it so because children are the hope of India’s future. I founded it not out of pity for street children, but admiration.”

Within a couple of years he left HSBC and enlisted the bank’s support for his new charity.

Over the past 32 years Future Hope has transformed the lives of at least 3,000 children by taking them off the streets and out of the slums of the city, now called Kolkata and the capital of West Bengal state, and giving them a home, medical care and an education. It has saved many from prostitution, drugs and poverty. Some of these children, who had no ambition when they arrived at the home, are now becoming lawyers, engineers, bankers and teachers.

Some 69 per cent of the girls sold into prostitution in India are from West Bengal, according to the latest statistics available from the National Crime Records Bureau, for the year 2013. There were more than half a million child labourers in the state, according to the 2011 national census.

Thousands of lost and abandoned children live in the railway stations or on the streets of the city, rummaging for crumbs and scraps. They are neglected, undernourished and extremely vulnerable to chronic illnesses and sexually transmitted diseases. There are boys who have run away from violent fathers; girls who have been raped by stepfathers; orphans; and drug addicts.

“One of the most upsetting sights I have seen is children as young as six unconscious on the footpaths or platforms,” says Grandage, now 62. “Drugs, alcohol and glue are often the cause, and are used by the children to numb the pain and deal with the hardships they face.”

He visits Howrah and Sealdah, Kolkata’s two biggest railway stations, at night, talking to the children, earning their trust and sometimes taking them for rides in his jeep.

At first, Grandage struggled to convince the boys and girls to come to Future Hope and then to get them to settle down.

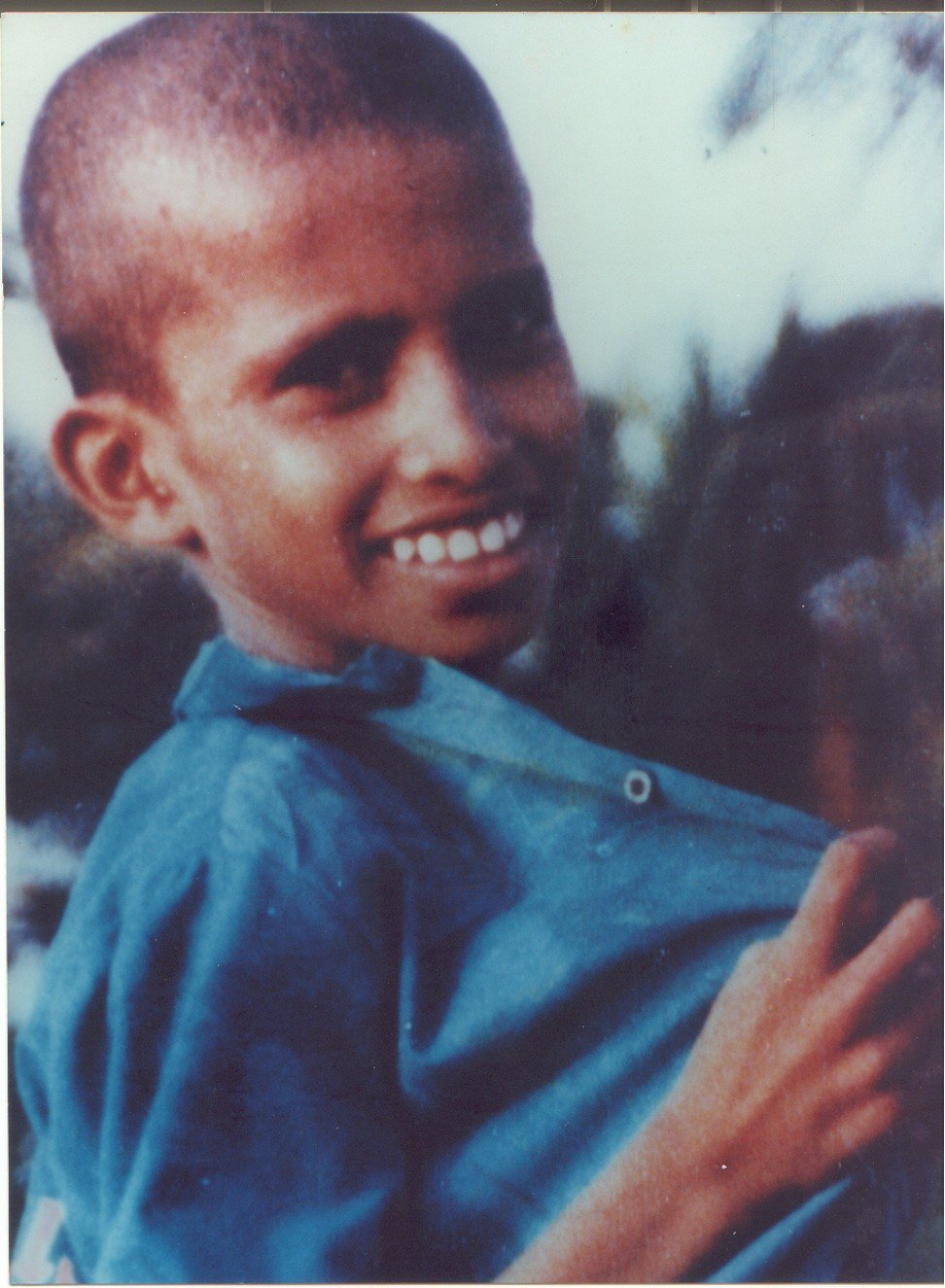

“I thought Tim Uncle was trying to lure me away to sell my organs,” says 37-year-old Sanjay Patra, who came to Future Hope as a skinny six-year-old boy, his body covered in scabies. After living so freely on the streets he found it impossible to settle down and he ran away more than 20 times before realising that his life would be better with Future Hope.

“He was not academic but showed a huge interest in sports, leading him to play rugby for the first Under 19 Indian national team,” says Grandage. “Today he is one of the best coaches in India and was the assistant coach to the Indian national team for two years. He is happily married with two children.”

Grandage says many have similar stories.

“The children have experienced unimaginable trauma and have been lost or rejected by their own family and society,” he says. “Two things became clear to me: they needed a routine and positive role models to mentor them.”

In 1992, Erica, a qualified nurse from Netherlands, arrived to volunteer at the charity.

“All of the children who come to us are malnourished, have low haemoglobin levels and intestinal disorders. Many of them have scabies, boils and underlying medical problems. We put them on a balanced diet immediately and get a full medical check done,” says Erica, who married Tim a few years after her arrival. The couple now have three children of their own.

Future Hope is an example of how sports can alter the lives of children – Mark Lambert, a professional rugby player with English side Harlequins

Today Future Hope houses about 130 children in six fully equipped hostels, called “homes”, with two dedicated local “house parents” in each home who look after the daily needs and upbringing of the children.

As many as 285 children from the six homes and the poorest families in the slums benefit from an all-round education at Future Hope School, and 40 per cent of them are girls. Many of the children go on to study at universities around India and a further 300 learn at the charity’s skills training centre in the city of Barrackpore.

Tim Grandage soon realised that the way to scale up the operation was to build a strong professional team, and to raise funds to make Future Hope sustainable.

At the helm is CEO Sujata Sen, who was formerly the director of the British Council Worldwide (the UK’s international organisation for cultural relations and educational opportunities) with more than 20 years of experience in education. She works with Samarjit Guha, director of Homes and Pastoral Care, a former journalist and ex-CEO of the Calcutta School of Music, and Madhu Ravi, principal of the Future Hope School, who has worked as an educationist in Delhi for more than 25 years.

Art, drama and sports play a significant role in rehabilitating the children. “We expose the children to classical and contemporary dance, Indian and Western music, drama classes, photography workshops and art classes to encourage them to explore different interests and nurture individual talent,” says Sen.

Today, 27-year-old Sitara is pursuing an honours degree in classical music and wants to become a music teacher. “When we found Sitara, he was six years old, homeless and living on the railway station,” Grandage says. “He was hungry, wild and completely deprived of love. He fell off a train and his leg was run over by the same train. Living your life on the streets is hard but surviving on the streets with disabilities is almost impossible.”

Music was his salvation. “Sitara loved our Saturday morning singing classes, instantly enjoyed playing the harmonium and took himself to weekly piano lessons,” says Sen. “School was not easy for him, but our career counselling team made him aware of the music degree course, and this became the driving force for him to complete class 12 and pursue his dream, a future in music.”

“Rugby is the perfect game for children who are tough but have no training in channelling their energy and aggression,” he says.

Future Hope’s rugby team was the Under 18 national champion team in 2017 and several boys have made it to the national team, with four boys currently in the junior national squad.

Mark Lambert, a professional rugby player with Harlequins, a top-level English rugby team, visits Kolkata once a year to train the Future Hope team. “Future Hope is an example of how sports can alter the lives of children,” he says.

Future Hope plans to build a new school with sports facilities on 10 hectares (24 acres) of land it has in Kashinathpur Rajarhat, a part of New Kolkata, to educate 750 children and build more homes to accommodate 220 children.

“Thousands of children still live on the streets and slums in Kolkata,” says Grandage. “My dream is that each one of them will have a home and become self-confident, contributing members of society one day.”

Future Hope Hong Kong Charitable Foundation is registered in Hong Kong as a charitable trust. To learn more, visit www.futurehope.net