A new exhibition in London (open until February 2026) called Thirst: In search of freshwater highlights how civilisations have treasured – and been intrinsically linked to – safe, clean water.

As a chemist, I research how freshwater is polluted by modern civilisation. Common contaminants in rivers include pharmaceuticals, microplastics (which degrade further when exposed to sunlight and wave power), and forever chemicals or per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) (some of which are carcinogenic).

Synthetic toxic chemicals are introduced into the environment from the products we make, use and dispose of. This wasn’t a problem centuries ago, where we had a totally different manufacturing industry and technologies.

Some, such as PFAS from stain-resistant textiles or nonstick materials such as cookware, can be particularly difficult to remove from wastewater. PFAS don’t degrade easily, they resist conventional heat treatments and can easily pass through wastewater treatments, so they contaminate rivers or lakes that are sources of our drinking water.

Get your news from actual experts, straight to your inbox. Sign up to our daily newsletter to receive all The Conversation UK’s latest coverage of news and research, from politics and business to the arts and sciences.

Testing for pollutants is even more critical in developing nations that lack sanitation and face drought or flooding. Having to protect and conserve drinking water and its sources is as relevant today as it always has been.

For this exhibition, curator at the Wellcome Collection in London, Janice Li, has selected 125 historical objects, photographs and feats of engineering that link to drought, rain, glaciers, rivers and lakes. These three artefacts from Thirst illustrate how our relationship with water contamination has evolved:

1. Ancient water filters

Made from natural materials such as clay, water jug filters have been used for hundreds of years in every continent by ancient civilisations. They show that purifying water for drinking was commonplace. The sand and soil particles that naturally get suspended in water and removed by these filters would have carried microbes.

But in ancient times, pharmaceuticals and other drugs, pesticides, forever chemicals and microplastics would not have been a problem. Those filters could work relatively well despite being made of simple materials with wide pores.

Today, those ancient filters would no longer be effective. Modern water filters are made using more advanced materials which typically have small pores (called micropores and mesopores). For example, filters often include activated carbon (a highly porous type of carbon that can be manufactured to capture contaminants) or membranes that filter water. Only then is it safe for people to drink.

Read more: Forever chemicals are in our drinking water – here’s how to reduce them

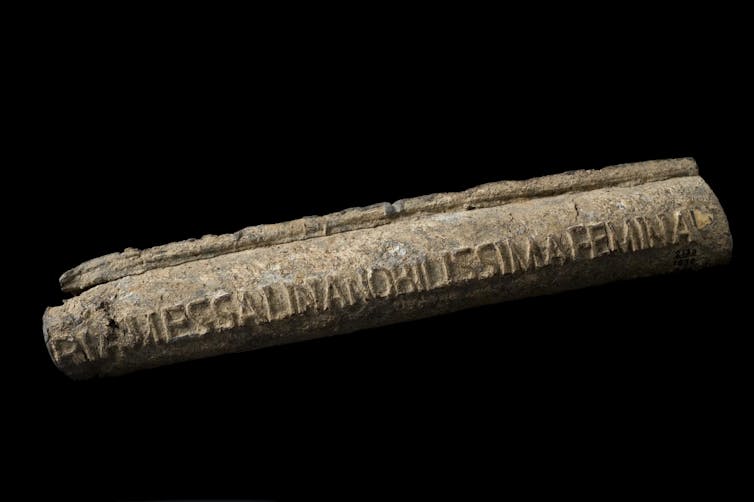

2. Roman water pipes

Lead water pipes (known as fistulae) were useful parts of a relatively advanced plumbing system that distributed drinking water throughout Roman cities. They are still common in water systems in our cities today. In the US, there are about 9.2 million lead service lines in use. Exposure to lead causes severe human health problems. Lead exposure, not necessarily from drinking water only, was attributed to more than 1.5 million deaths in 2021.

It’s now understood that lead is neurotoxic and it can diffuse or spread from the pipes to drinking water. Lead from paints and batteries, including car batteries, can also contaminate drinking water.

To protect us from lead leaching or flaking off from pipes, some government agencies are calling for the replacement of lead pipes with copper or plastic pipes. Water companies routinely add phosphates (mined powder that contains phosphorus) to drinking water to help capture potential lead contamination and make it safe to drink.

3. The horror of unhealthy water

One caricature titled The Monster Soup by artist William Heath (1828) is part of the Wellcome Trust’s permanent collection. The graphics read “microcosms dedicated to the London Water companies” and “Monster soup, commonly called Thames Water being a correct representation of the precious stuff doled out to us”. The cartoon shows a lady so terrified at the sight of microbes in river water from the Thames that she drops her cup of tea.

Even today, many people remain shocked at the toxic contamination in rivers and sewage pollution prevents people from swimming.

By 2030, 2 billion people will still not have safely managed drinking water and 1.2 billion will lack basic hygiene services. Drinking water will still be contaminated by bacteria such as E. coli and other dangerous pathogens that cause waterborne diseases. So advancing technologies to filter out contamination will be just as crucial in the future as it has been in the past.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 45,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.

Rosa Busquets receives funding from UKRI/ EU Horizons MSCA Staff exchanges Clean Water project 101131182, DASA, project ACC6093561. She is affiliated with Kingston University, UCL, Al-Farabi Kazakh National University, UNEP EEAP.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.