Nina Khrushcheva, a professor of international affairs at the New School in New York, went back to Moscow recently to complete work on her forthcoming book, a biography of the Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev—her great-grandfather. Khrushchev was the first Soviet premier to visit the United States, in 1959. To many Americans, he is best remembered as the leader during the Cuban missile crisis of 1962. He agreed to remove Soviet nuclear missiles from Cuba in exchange for President John F. Kennedy’s promise that the U.S. would not invade the island.

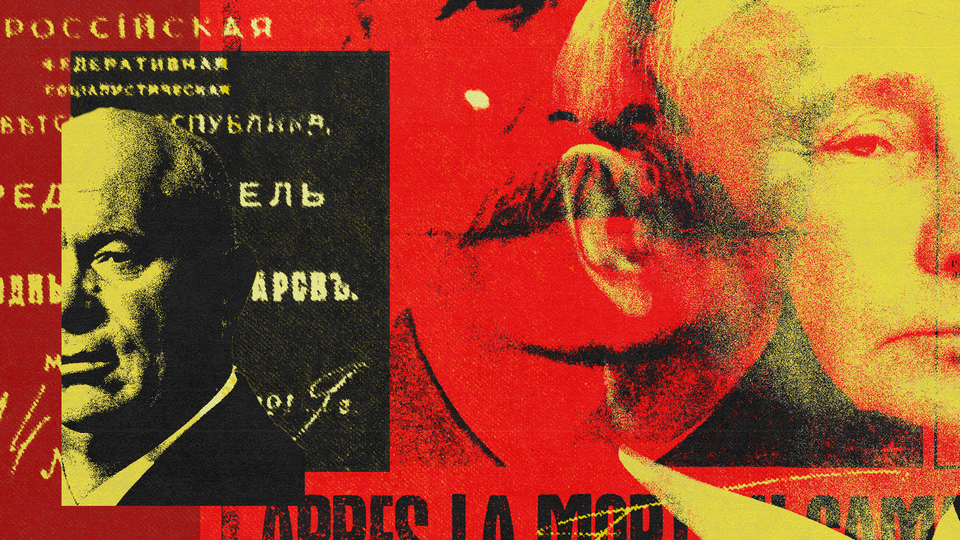

In Russia today, Khrushchev’s memory has been almost completely erased from public discussion, even though he led the post-Stalin U.S.S.R. through what was arguably its most hopeful time. In that era, from 1953 to 1964, the Soviets were competing with the U.S. in the space race; Khrushchev even boasted that the U.S.S.R. was close to overtaking the U.S. as world leader. And a period of liberalization known as “The Thaw” seemed to consign the show trials, purges, and mass murder of the 1930s to communism’s dark past. Yet the Kremlin today conspicuously overlooks Khrushchev.

When we spoke before she left for Moscow, Khrushcheva told me that she has been “missing Grandpa,” as she calls him. The Soviet premier, who was ousted in 1964, died in 1971, but Khrushcheva remembers him well from her youth. Born in 1963 and raised in Moscow, she came to the U.S. to attend graduate school at Princeton in 1991, at the very twilight of the Soviet Union. Today, she reflects on Khrushchev’s legacy and on Russia’s current conflict in Ukraine, which President Vladimir Putin has threatened to make nuclear. This is an edited and condensed transcript of our conversation.

Anna Nemtsova: Sixty years ago, Khrushchev did not want a nuclear war, so he struck a bargain with Kennedy—and was later criticized by his politburo for making Moscow look weak in America’s eyes. Do you feel proud of Khrushchev’s decision to prevent a nuclear confrontation then? Do you fear such a conflict might actually happen today?

Nina Khrushcheva: Not proud necessarily, because this would have been the only possible decision. But certainly I think that he and Kennedy handled the crisis in the right way. Yet the debate in Russia today is very unsettling. Putin said recently at a conference in Moscow, “We see no need” to use nuclear weapons; a few days later, the former president and Putin’s deputy chairman on the Security Council, Dmitry Medvedev, made a statement to the effect that if Russia faces sufficient threat as a result of the war in Ukraine, it will have to use nuclear weapons. Which one is Russia’s official position?

Nemtsova: Putin has dissociated himself from Khrushchev. Why do you think there is so much resistance to acknowledging the Khrushchev era in today’s Kremlin?

Khrushcheva: In his memoirs, the Russian writer Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn discusses how Khrushchev kept up an appearance of sticking to the party line but actually kept breaking out of its dictatorial formulae. In this, Khrushchev was everything that Putin is not. Khrushchev was chaotic and emotional. Putin sees himself as consistent and a technocrat.

When Putin says he can’t imagine himself as Khrushchev, does it mean he wouldn’t have got into the Cuban missile crisis at all? Or that if a nuclear crisis does happen, he will be uncompromising where Khrushchev was flexible? So far, Putin has only escalated tensions, whereas Khrushchev made serious efforts to deescalate his confrontation with the U.S. in 1962.

Nemtsova: Was Khrushchev not hard enough for Putin, not enough of a dictator? Or does Putin see Khrushchev as a reminder of a humiliation by the West?

Khrushcheva: The erasure of Khrushchev that has continued under Putin started with the rise of Stalin worship in the early 2000s. Khrushchev’s political tragedy is that he is not democratic enough for the liberals, yet not dictatorial enough for the Stalinists.

Khrushchev rarely gets credit nowadays—even official references to Sputnik, Yuri Gagarin, and the Soviet space program fail to mention that these were achievements of his leadership. In recent remarks, Putin spoke about colonialism and how the Soviet Union was the first to address that issue on the world stage, which makes him proud. He didn’t, of course, mention Khrushchev, but it was fully Khrushchev’s initiative in 1959 and 1960 to press for the rights of formerly colonized nations at the United Nations.

Most likely, Putin thinks that Khrushchev was a fool, as do many hard-liners. Khrushchev asked for concessions from Kennedy, but he also made concessions himself. The KGB tradition doesn’t believe in concessions; it believes in victory at all costs. Under Khrushchev, the KGB was made subordinate to the Communist Party and lost a lot of its power. The agency never forgave him. Putin, a former KGB lieutenant colonel, allegedly quipped at the start of his Kremlin career, “The task of infiltrating the highest level of government is accomplished.”

Nemtsova: What is the main difference between Khrushchev’s and Putin’s close circles?

Khrushcheva: Khrushchev was a man who acted despotically at times—he was part of a despotic system, though he constantly tried to change it. And by the end of his rule, the system had changed him. Power in Russia has always been vertical, and Khrushchev ultimately had too much of it. My grandmother Nina used to say, “Nikita Sergeyevich of 1958 is not Nikita Sergeyevich of 1962.” But unlike now, there was a politburo, or the presidium, as it was known at the time. There were discussions, somewhat collaborative decision making, even opposition. What passes for the politburo today follows the vision of one KGB man at the top.

There was a lot of absurdity in Soviet life under Khrushchev. And there were state crimes such as the massacre of striking workers at Novocherkassk in 1962. But Soviet life was not dystopian. Putin’s Russia is fully dystopian. Its absurdities are tragic, and the tragedy is on a far greater scale. Although Khrushchev came out of the Stalin era, he grew away from Stalinism. Putin emerged during a time of promise for Russian democracy, yet Khrushchev appears to have been a greater democrat than Putin is.

Nemtsova: Today, many say that reformers should have done a better job of reining in the KGB machine long before Putin. Could Khrushchev have done more to dismantle the security apparatus?

Khrushcheva: Khrushchev was one of the leaders behind the execution of the KGB chief Lavrentiy Beria in December 1953. Everyone in Stalin’s entourage after his death was afraid that Beria would kill them. He’d set up the whole web of spying on everyone; he knew their most intimate secrets that could have been used against them when needed. Khrushchev and Georgy Malenkov lived in the same building in Moscow, and Beria knew all of their movements: The cooks, the cleaners, the guards—everyone was on his payroll.

After Beria’s arrest in the summer of 1953, Khrushchev brought home the Beria files and told Grandmother to look them over so she could understand the horrors of that regime. Grandmother told me that she managed to read only three pages and gave up—what she read was so horrible, she could hardly believe it. But Khrushchev’s mistake was to think that the KGB problem was a problem of personalities—of Stalin, of Beria—rather than a problem with the system.

Today, Russia’s problem is very clearly one of a despotic system of government that needs a security apparatus to preserve and defend its existence. Khrushchev tried to change it but ran out of time. He thought a new generation would come along and make democratic changes. He was wrong.

Nemtsova: What are your impressions of Moscow today?

Khrushcheva: It feels as though everyone is frozen in despair, stressed, unsure of the future. Some people are pretending that nothing is happening, but quietly all of one’s conversations are about this. There are fewer foreigners here, more stores closed, and lots of police everywhere.

The woman in charge of distributing the military draft notices in my building said, “It’s horrible; it can’t go on like this.”

I said, “But you work for the government.” And she replied, “What can I do?”