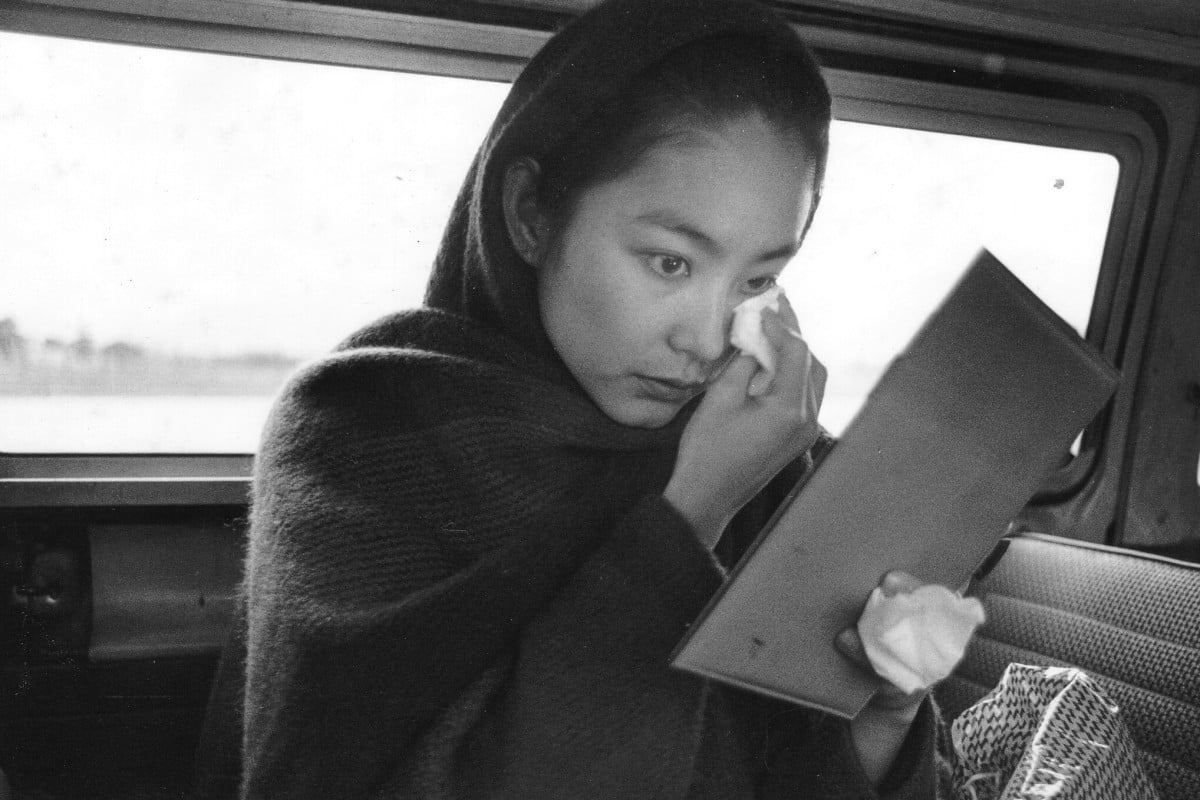

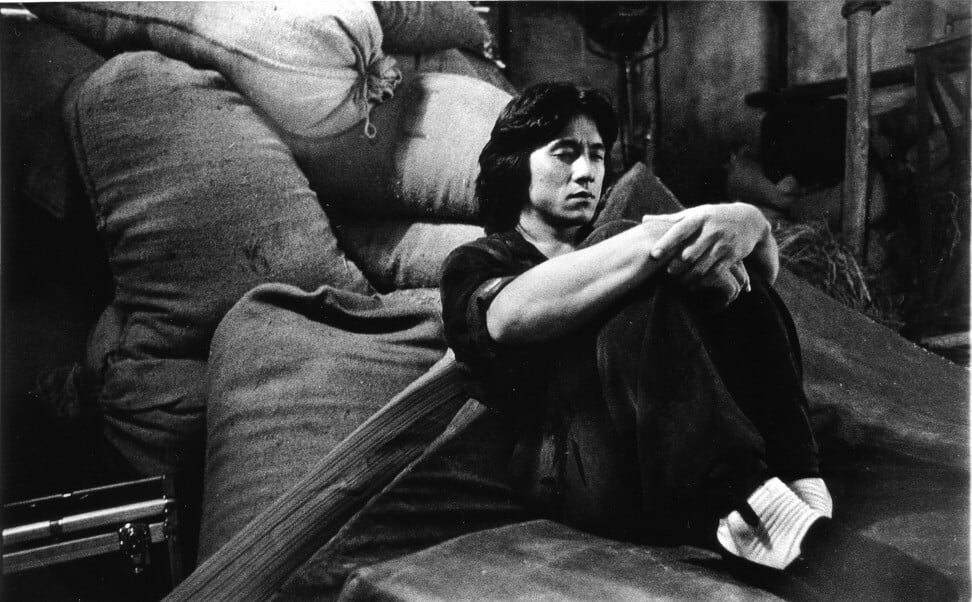

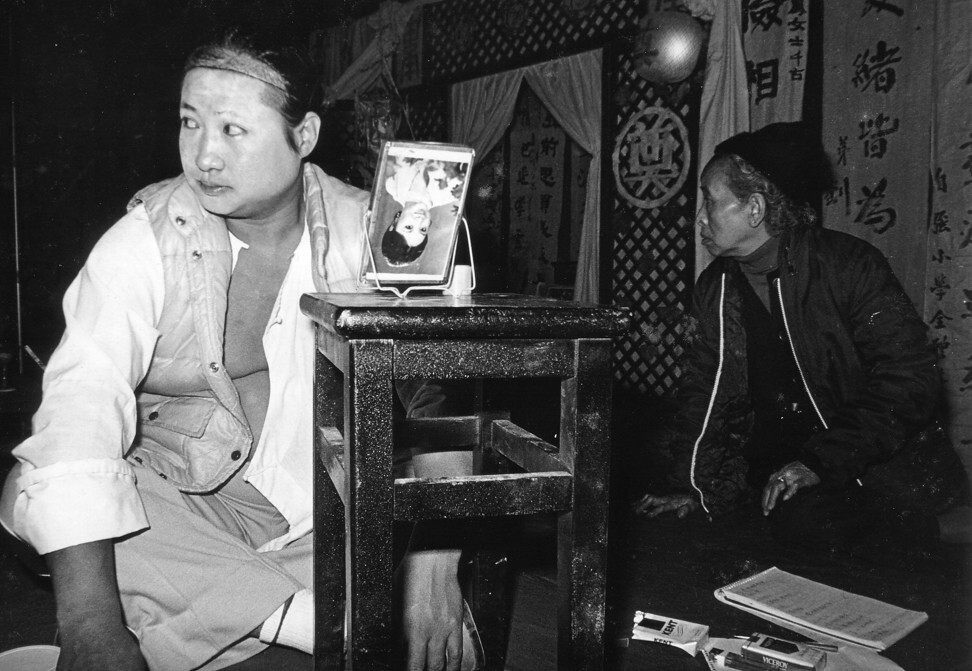

Hiding in a corner on a movie set, Jackie Chan looks despondent after messing up a shot. Wearing only underpants and standing next to an extra on set, Canto-pop singer George Lam Chi-cheung waits for the shooting of a bedroom scene to begin. Holding up a mirror, Brigitte Lin Ching-hsia gingerly dolls herself up in a camper van.

Superstars of Chinese cinema were captured in such private moments by Lo Yuk-ying, a former part-time movie producer, and feature in a new edition of her photo book The Film Makers, to be released on July 15.

The collection of around 100 pictures were shot for Lo’s column about people working in the Hong Kong film industry which appeared in the bi-weekly Hong Kong movie magazine City Entertainment Magazine between 1979 and 1983. Lo co-founded the magazine in 1979 with other film buffs.

A self-taught photographer, she says that, unlike today, when films and movie stars are plugged relentlessly online, there were no promotional channels for entertainment celebrities in the old days.

“In the ’70s we set up the Phoenix Sine Club, which organised the first-ever film festival in Hong Kong. We showed art-house movies like [Vittorio De Sica’s 1948 classic] ,” Lo says. “We had to rent the films from overseas and got them at the airport. We all worked pro bono for City Entertainment Magazine. Besides doing the column, I also worked as editor and did typesetting for the magazine.”

Lo had a daytime job as a teacher, and took the pictures when she worked as a part-time general manager and producer for Tsui Hark’s film company because of her love of cinema. Besides being published in City Entertainment Magazine, Lo’s photographs also appeared in City Magazine, co-founded in 1976 by Hong Kong author Chan Koonchung.

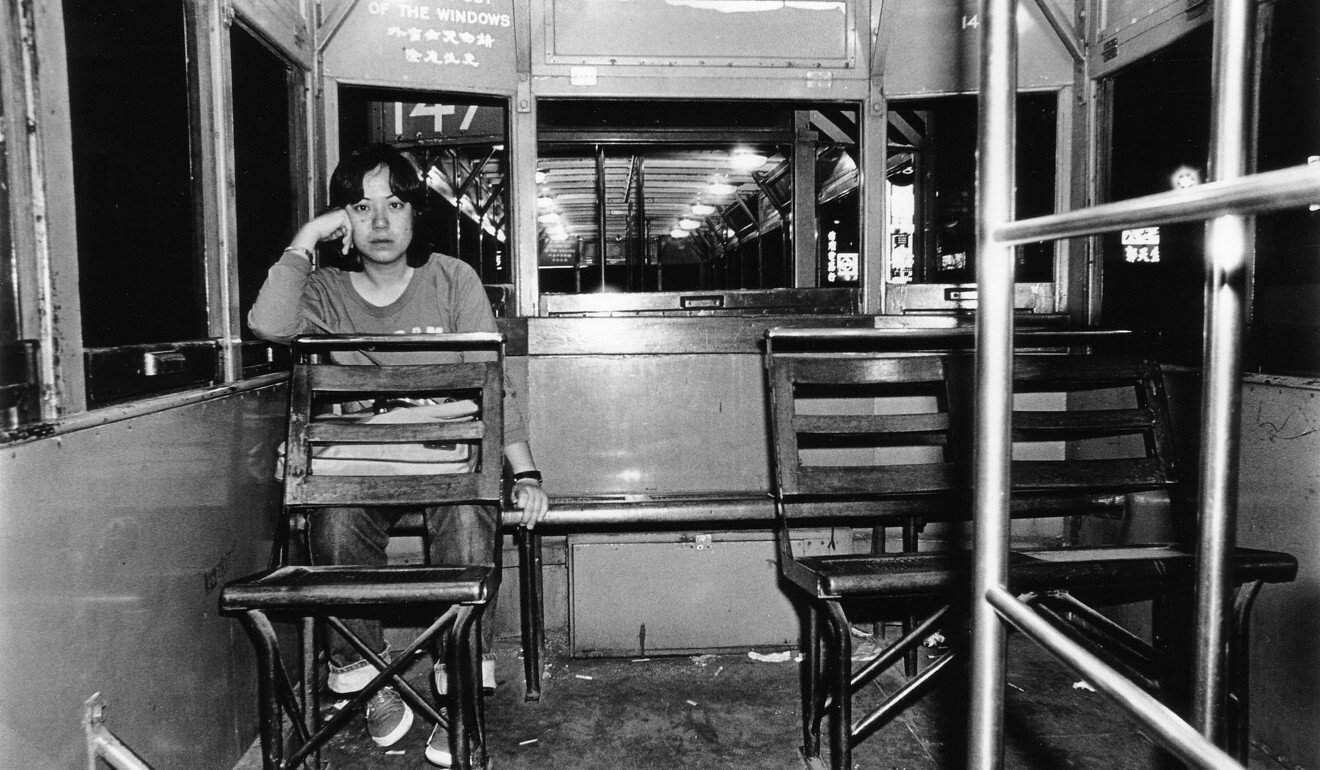

Using a Minolta camera with 28mm lens, which was a gift from her father, Lo shot director Ann Hui On-wah for her first column for City Entertainment Magazine.

“Having just finished making her first movie The Secret (1979), she was very nervous then, as she was still exploring [the direction of] her career. So I put her on a tram and asked her to sit at the back to capture her feelings of anxiety of being in a strange environment,” Lo says.

Lo considered the star-making industry an illusion, and says she was not interested in capturing inauthentic images.

“I seldom asked my subjects to pose for me, as I wanted to show their true selves, not a stage-managed version of themselves,” she says.

She cites as an example the portrait she took of Kwan Tak-hing, a legendary Hong Kong actor best known for his portrayal of Guangdong martial arts master Wong Fei-hung in more than 70 films between the 1940s and the 1980s.

“He always looked imperious, like an emperor, opening his eyes wide. I waited until he closed his eyes to relax for a moment to take the picture.”

With phalanxes of handlers and PR personnel managing all daily activities of stars, Lo says capturing filmmakers in an unguarded and vulnerable state would be unthinkable today.

“Very few of my photo shoots were arranged affairs,” says the photographer, who is influenced by the likes of Robert Frank, William Klein and Garry Winogrand, all renowned for their work in documentary photography.

“I would call up film companies to get the locations and schedules of movie sets,” Lo recalls. “I just showed up on the spot. People [on set] knew who I was and respected me, as they knew my column was aimed at promoting the film industry,” she says.

“The pictures I took of the stars are in-the-face shots. I don’t like zooming in from afar. I didn’t care how the stars felt. I went away once I took my picture. I treasured film a lot then. I only took one picture [for each subject] and I never scrapped pictures [I took].

“When I took the shot of a contemplative Jackie Chan, I had waited for a whole night on set to capture that single moment. He was throwing a temper after messing up a shot. He was pondering how to make the shot.”

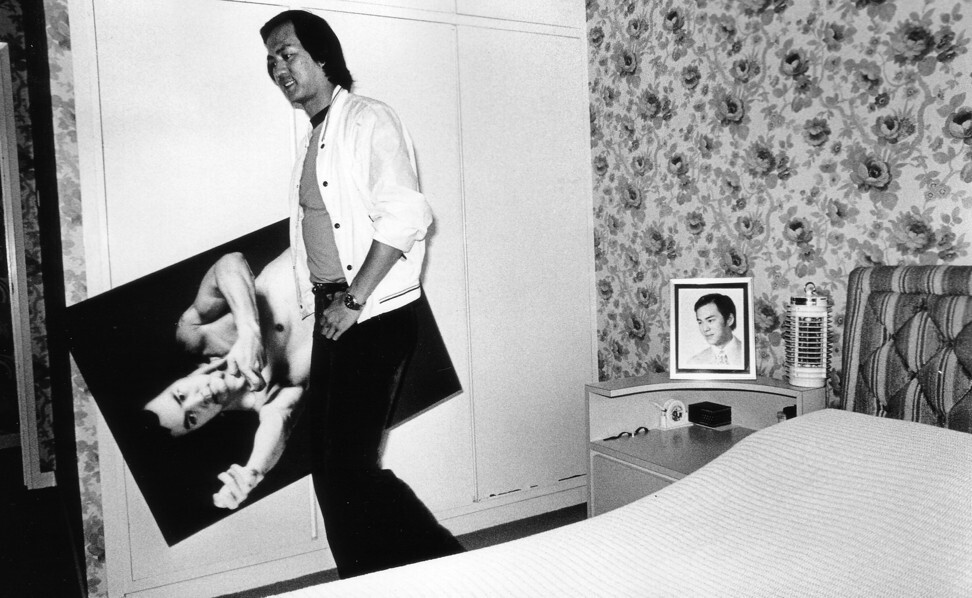

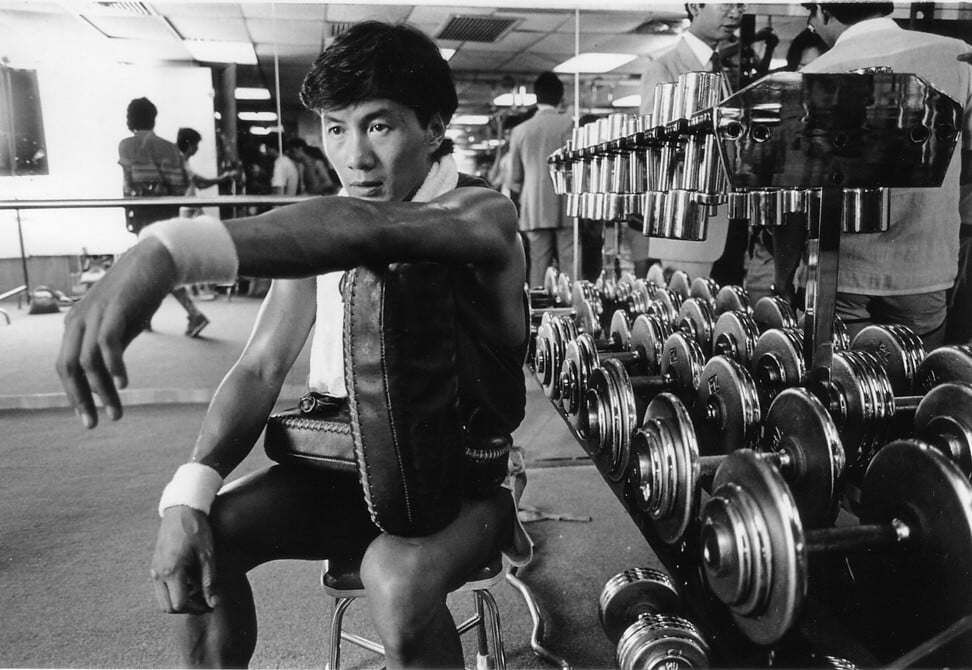

A rare exception to Lo’s practice was when she took a portrait of Tommy Tam Fu-wing, better known by his stage name Ti Lung. Her picture shows Tam carrying a portrait of himself in his bedroom.

“[After arriving at his place], I took a quick look around. There were many pictures which showed only him, but not his wife. In his bedroom with flowery wallpaper, a portrait was on the bedside table.

“I thought only a woman would make such a [bedroom] arrangement, which was at odds with his image. So I asked him to carry a big portrait of himself and took a picture of his muscle-bound self against his bedroom wall [to show the contrast between his public image and his real inner self].

“I didn’t ask for approval for the publication of pictures. If Tam was upset after seeing the picture, there was nothing I could do about it.”

While the pictures were taken more than three decades ago, Lo can still recall the moments she shot them with vivid clarity.

“The pictures capture the golden era of the Hong Kong film industry. It was also the best time for you to be an [entertainment] reporter. I wouldn’t get used to working under the current system where people would ask me what I am doing on set or even frisk me, looking for my camera to see what pictures I have taken.”

In a preface for the new edition of The Film Makers, Tsui Hark writes that the subjects of Lo’s photos are all his friends. “I feel special looking at them reflected in her pictures, which show [another side of them],” he writes.

“Her camera has the magic to [help the viewers] discover the inner world of her subjects. I couldn’t imagine that Lo can capture the momentary real humanity of [all those stars] in their private space. Their inner selves might be hidden even to [the subjects themselves].

“Whenever I look at the picture she took of me looking melancholic [in the 1980s], I always smile. I remember what was on my mind when she took the picture after I wrapped up filming Zu: Warriors from the Magic Mountain. I thought that would be my last work.”

Tsui also points out that much has changed in the film industry since the first edition of the book was launched in 1985. “Some of the subjects in her pictures have [grown old], passed away or retired. …[Looking at the pictures again allows me] to revisit the studio sets.

“Today’s Hong Kong is facing all kinds of huge difficulties. The film industry is also in the throes of uncertainty. Reading Lo’s book, I know Hong Kong filmmakers overcame many hurdles to [help the film industry develop]. I hope the current and future generations will continue the efforts of their predecessors [to keep the flame of Hong Kong cinema burning].”

Want more articles like this? Follow SCMP Film on Facebook