Med-tech hit the consumer mainstream with Apple’s announcement on 9th March of ResearchKit, an open source software framework that can be used to develop iPhone apps that gather data for medical and healthcare research.

Healthcare apps have evolved from fitness trackers to actively monitoring and managing medical conditions. Based on ResearchKit, University of Rochester is developing mPower, an app that assesses the progression of Parkinson’s disease by listening to the user’s voice and measuring dexterity.

Propeller Health’s asthma inhaler device links to patients’ smartphones via Bluetooth logging the time and location each time it is used. The information is then analysed to correlate where people use their inhalers with the surrounding environmental conditions and sends alerts via an app to help patients and physicians manage and control the condition.

These developments – and the potential that they offer – are driving investment in med-tech and influencing the structure of med-tech businesses. M&A deal volumes in med-tech in 2014 were 13% higher than in 2013 and this trend is set to continue in 2015.

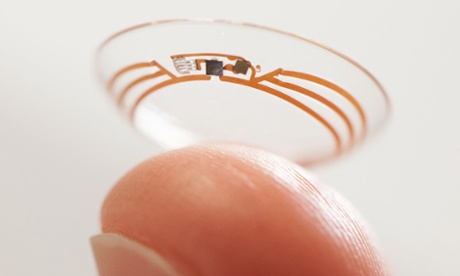

The NHS recognises that med-tech devices have a demonstrated clinical effect when it comes to managing chronic conditions such as diabetes and provides some funding for continuous glucose monitoring (CGM). Google is working with Novartis to make a glucose-monitoring contact lens and was recently granted a patent by the US patent authorities. In January, Novartis and Qualcomm launched a $100m joint investment fund for ‘technologies, products or services that go beyond the pill’.

Embedded and wearable medical devices are not new; what is new is the ability to collect and analyse large volumes of real-time patient data, bringing together measurements from multiple devices and apps to gain insights into medical conditions and treatments.

Data analytics

Data analytics detect patterns of illnesses and diseases and identify genes that may help or hinder the effectiveness of treatment as well as patterns of recovery/survival. This can support diagnosis and developing treatments.

Smart devices have helped to advance telemedicine, where real-time data is sent to a specialist clinician in a different location. This is particularly useful in enabling patients in remote locations, or who require particular expertise, to access advice and treatment in real time.

However, this convergence between consumer and medical technology raises legal and regulatory issues. As Olswang partners Dr Robert Stephen and Stephen Reese explain, smart devices and apps require user consent for the collection and use of personal data. The legal and ethical concerns are around data security and privacy and, importantly, permission. “Personal data is protected by the Data Protection Act and the closest thing we have to a right of privacy in UK law is how our data is processed and held,” says Reese. “In relation to medical data there is also a common law duty of confidentiality between the patient and the medical profession. Ultimately it comes down to patient consent.”

On 12th and 13th March, the EC judicial and home affairs committee discussed new data protection regulations. “Where the new regulations are looking to get tighter and more restrictive is that consent must be specific, focused and clear,” says Reese adding that ‘personalised medicine’ requires people to understand precisely where and how their data is used. These issues have led to the NHS postponing the introduction of the central database care data because of patient concerns about data breaches.

Data security is a key concern. “Given the reputational issues around data security, organisations that hold patient data will want to place obligations of confidentiality on their cloud hosting providers to make sure the data is not lost or misused. It is about protecting their reputations, and their investment in the data,” says Stephen. “If patients and participants in medical research don’t believe their data is secure, confidential and not sold on to third parties, they will not consent for it to be used.”

Matt Pfeil is chief customer officer at DataStax, creator of open source database software Cassandra, which is used by companies that collect data to personalise user experience – such as Netflix and Spotify – and increasingly for internet of things (IoT) applications. Amara Health Analytics uses Cassandra to monitor and analyse patient data in real-time. It is particularly valuable to diagnose and monitor conditions like sepsis which can develop rapidly and send doctors alerts when this happens so that action can be taken very quickly.

Although DataStax does not host its customers’ data, Cassandra includes security elements such as data encryption. “The organisations that provide the best user experience are the ones that do the best with their data, and that includes keeping it safeguarded. Data security is improving as more is moving to the cloud,” says Pfeil. “Regulation is important to set standards and protect data owners’ right to decide what happens to their data.” Pfeil emphasises that smart med-tech is possible only because technology has advanced to the point where sensors can be manufactured cost-effectively. “So although regulation is important to maintain users’ rights and ability to control their own data, I worry that too much regulation will slow down innovation,” he says.

Regulating medical devices

In the US, the FDA have stepped up their interest in approving med-tech devices. There is talk of the EMA taking a greater role in regulating medical devices, but nothing has happened yet. As more people use med-tech apps and devices, governments and regulatory authorities will be forced to become more involved.

Propeller Health co-founder and CEO David Van Sickle sees regulation as a framework for developers. “Propeller is a class II medical device, so we go through the FDA regulatory clearance process which includes the sensors attached to the medicines (inhalers), the smartphone apps and the patient-facing websites,” he explains. “We consider regulation as part of good preventive practice, helping to generate higher-quality products and patient and physician confidence that products are safe and effective. Regulations are good guideposts for our software and hardware development.”

The data collected by med-tech devices and apps is often highly sensitive. If it is passed on to other organisations in the interests of advancing medicine this needs to be done with patients’ permission.

According to Reese at Olswang, “The challenge will be that individuals will be asked to consent to sharing their data on a trial-by-trial basis and this may limit participation in medical research.”

The data automatically collected by the Propeller device is used in two ways: to feedback to patients what might trigger their symptoms both individually and collectively, for example by producing maps based on patterns of use; it is also linked to physician teams so that they can understand asthma better and improve their ability to manage it. This ‘passive’ data collection is deliberate. “We did not want to give patients the additional burden of expecting them to use an app to record events,” explains chief technology officer and co-founder Greg Tracy.

Protecting privacy

Potential data privacy issues are addressed by giving patients the ability to decide which information to share. “The data we collect is encrypted and access to it is limited. The system includes fine-grain permissions, so that users can decide which pieces of data are shared and who gets to see it,” says Tracy. Recognising that location data can be highly revealing, the team suppresses this type of data from publicly shared maps. “We allow individuals to set permissions on an event-by-event basis or across the board,” adds Van Sickle.

Stephen at Olswang wonders whether willingness to share data is generational – and cultural. “However, in the fitness space, it will be interesting to see whether younger users who are generally more comfortable with using the technology and sharing their own personal data, will realise any health benefits over the long term, which may indeed be difficult to assess in this comparatively healthy cohort.”

Med-tech is revolutionising healthcare, but to be successful, device developers and lawmakers need to remember that this is about people, not data points. Unlike other industries, where data is used to enhance customer experience, the ultimate purpose of collecting real-time medical data is to advance medical science and improve individual and collective healthcare.

Joanna Goodman is a writer and editor. Follow her on Twitter @JoannaMG22

This advertisement feature is provided by Olswang, sponsors of the Guardian Media Network’s Changing business hub