In the thrilling finale of the TV series The Americans, set during the Reagan administration, deep-cover KGB operatives Philip and Elizabeth Jennings are faced with a difficult decision. Posing as an ordinary American married couple, for decades they have raised children, filed tax returns and slipped effortlessly into the rhythms and routines of everyday suburban existence in Washington, D.C.

All the while, they’ve been spying – gathering intelligence and surreptitiously feeding it to their communist masters in Soviet Moscow. Now, with the FBI closing in and their cover on the brink of collapse, they must decide whether to stay and face arrest or flee the country they’ve come to call home. There’s also their teenage children to consider.

The story seemed too incredible to be true – but in fact it was based in part on Donald Heathfield and Ann Foley, subsequently outed as Andrei Bezrukov and Elena Vavilova, a Russian couple who had spent more than 20 years masquerading as Canadians. At the time of their unmasking, they were living quietly in the United States with Tim and Alex, their two sons.

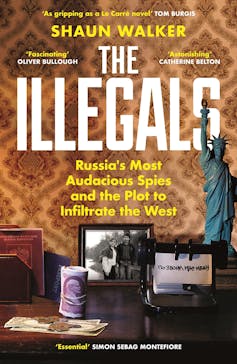

Review: The Illegals: Russia’s Most Audacious Spies and the Plot to Infiltrate the West – Shaun Walker (Profile)

A new book, The Illegals, tells of a network of Russian agents operating across the US, during the late 20th and early 21st centuries – including Bezrukov and Vavilova. It opens with their dramatic 2010 arrest, part of ten Russian spies (mostly illegals like them) detained by the FBI.

Author Shaun Walker, the Guardian’s central and eastern Europe correspondent, draws on declassified archival material and first-hand interviews. The result is an engrossing, eye-opening account of the secret world of the Soviet “illegals programme”: embedded spies who lived surreptitiously in the West without the safety blanket of diplomatic protection.

As Walker explains, “legals” were Russian operatives working under official cover – as diplomats or embassy staff, privy to diplomatic immunity. By contrast, “illegals” operated off the grid. They crept silently into Western countries under false identities, often stolen from the dead. This made them harder to detect, but left them far more vulnerable if exposed.

One of the most high-profile figures in the 2010 spy bust was Anna Chapman. Unlike many other illegals, Chapman didn’t even bother to disguise her Russian identity. Instead, as Walker recounts, she entered America using a British passport – acquired through a brief marriage to a UK citizen – and worked as a New York real estate broker.

Her photogenic looks and media-friendly persona made her the public face of the scandal. After being deported, Chapman reinvented herself as a television host, runway model and pro-Kremlin influencer.

The real Americans

Walker outlines how Bezrukov and Vavilova first met in the early 1980s, as history students in Siberia. There, KGB “spotters” identified them for potential recruitment. Later, he adds,

they progressed to an arduous training programme lasting several years, moulding their language, mannerisms and identities into those of an ordinary couple. They left the Soviet Union separately in 1987, staged a meeting in Canada, and began a relationship as if they had just met.

Having married under their assumed names, Andrei and Elena adopted the habits and customs of an ordinary middle-class life. After the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, the couple were cut off from Moscow, but by the end of the decade they were reactivated by the SVR, Russia’s new foreign intelligence agency. Around this time, Andrei won a place at Harvard’s Kennedy School, allowing the family to move to Massachusetts and integrate further into American society.

As Andrei networked in academic and policy circles, Elena maintained the illusion of domestic normality, fashioning herself as a doting “soccer mom”, raising the kids and keeping house. Meanwhile, she was secretly decoding encrypted radio messages in the back room.

This went on for years. Then, one day, an unexpected knock on the door as they celebrated their son Tim’s 20th birthday brought the charade crashing down. FBI agents burst in, handcuffed the couple in front of their sons and marched them out into the street.

Soon after their arrest, Andrei and Elena were deported to Russia in a high-profile spy swap. They were awarded state honours by Vladimir Putin and briefly became minor celebrities in Moscow. Their sons, both born in Canada, were left reeling.

In 2016, Walker tracked the sons down for a piece he was writing for The Guardian: they were in the process of suing the Canadian government to have their citizenship reinstated, having been stripped of it when everything kicked off. In 2019, a court ruled Tim and Alex (who was 16 when the FBI arrested his parents) could keep their citizenship. Both insisted they had known nothing about their parents’ espionage work.

Putin ‘beside himself’

As Walker recounts, the raid had been coordinated by then-FBI director Robert Mueller. It had been timed to avoid derailing a carefully planned diplomatic summit.

In 2009, Barack Obama launched a high-profile “reset” of relations with Russia. Obama wanted to woo Dmitry Medvedev – a moderate political figurehead standing in for Putin, who remained the real power behind the scenes in Russia.

A planned summit in Washington intended to cement the spirit of renewed cooperation. But as the scale of Russia’s covert operation became apparent, the White House was faced with a dilemma: how to respond without jeopardising the reset.

According to Walker, Obama was irked by the whole situation. He quipped that it felt like something out of a John Le Carré novel. Eventually, a compromise was reached: the arrests would happen, but only after Medvedev’s visit, so as not to cause undue embarrassment.

Colonel Aleksandr Poteyev, deputy head of Directorate “S” of the SVR, was the man overseeing the illegals scheme. After the arrests were made, he quietly walked out of the agency headquarters in Yasenevo for the last time. He was the mole who had tipped off the Americans. From there, he made his way to Ukraine, where the CIA could safely extricate him to the US. On hearing the news, Putin was reportedly beside himself with rage, Walker writes.

Intrigued by this “twisted family story”, Walker started to look into the illegals venture in greater depth. He quickly realised “there was nothing quite like it in the history of espionage”. At times, various intelligence agencies had deployed operatives as foreign nationals, “but never with the scope or scale of the KGB programme”.

A century of dramatic, bloody history

The illegals were, in Walker’s reckoning, something uniquely Russian, rooted in the country’s complex historical experience. The more he read, the more he came to view the programme as a lens through which he could “tell a much bigger story, of the whole Soviet experiment and its ultimate failure, a century of dramatic and bloody history”.

To understand how the illegals project came about, Walker winds the clock all the way back to 1917, when the Bolsheviks seized power – and espionage became a cornerstone of the nascent Soviet state. He reminds us while Lenin and his comrades had won formal control of the nation, “they still faced the colossal task of implementing and retaining it across the vast Russian landmass”.

Gripped by his belief in the predictive principles of historical materialism,

Lenin was sure that state institutions would eventually wither away, the evolving worker’s paradise rendering them meaningless. However, to achieve this happy end point, he believed an interim period of ruthless state violence was required.

The Cheka: precursor to the KGB

This helps to explain why he established the Cheka, a secret police force tasked with crushing counterrevolutionary activity and enforcing Bolshevik rule. At its head was Feliks Dzerzhinsky, a fanatical Polish ideologue who had spent years in Siberian exile. Far from a temporary measure, the Cheka “quickly grew to a huge fighting force that could be unleashed on political and class enemies”, Walker writes.

The Cheka was an important player in the Russian Civil War, which pitted Lenin’s Reds against the Whites – a loose alliance of pro-tsarist regiments and foreign mercenaries, often united by little more than their implacable hatred of Bolshevism. The situation on the ground was chaotic and unpredictable; both sides engaged in ruthless violence.

Here, in this blood-drenched crucible, the Bolsheviks honed their clandestine methods – konspiratsiya (subterfuge) – perfecting the use of disguises, false identities and underground communication. In areas where the Whites gained a territorial foothold, agents were ordered to stay behind and coordinate resistance, laying the groundwork for what would become the illegals programme.

When the Bolsheviks emerged victorious in 1921, the Cheka was not disbanded – but repurposed. The practice of planting operatives deep inside enemy lines survived the war and expanded in scope. Lenin’s idea of combining legal diplomatic work with illegal undercover infiltration became a defining feature of how the Soviet Union would run its intelligence services for the next 70 years.

Stalin’s secret police

Under Lenin’s successor, Joseph Stalin, the secret police was transformed into an all-encompassing instrument of surveillance, repression and domination.

Purges consumed the party. Ideological fervour curdled into show trials and murderous terror. And paranoia became an organising principle of Soviet political life. The demand for vigilance intensified – not just at home, where informants and denunciations became routine, but also abroad. Real and purported enemies were seen lurking in the democratic institutions of the West.

Ironies abound here. The very methods that helped to sustain the early Soviet state – secrecy, trickery, duplicity – soon became grounds for suspicion on Stalin’s watch. The generation of illegals trained and embedded during the 1920s and early 1930s were among those earmarked for liquidation, Walker writes. Stalin, ever wary of plots against him, came to view his own spies as potential traitors.

He ignored – or wilfully dismissed – much of the intelligence they had risked their lives to gather, often with disastrous consequences. When advance warnings of Operation Barbarossa, Hitler’s secret plan to betray Stalin and launch a massive invasion of the Soviet Union, landed on his desk in 1941, for instance, they were waved away as provocation or outright fabrication. In some cases, he had his spies tortured or shot. Loyalty was no protector against paranoia.

Among the casualties was Dmitry Bystrolyotov, who Walker describes as “perhaps the most talented illegal in the history of the programme”. A truly chameleonic figure, Bystrolyotov was a dashing and multilingual agent whose exploits in Western Europe made him a legend in Soviet intelligence circles. “His speciality was the recruitment of agents who had access to diplomatic codes and ciphers,” the Russian scholar Emil Draitser attests, “and his modus operandi involved women”.

Through a series of painstakingly crafted affairs, Bystrolyotov gained access to confidential dispatches, internal memos and state secrets. His work offered Stalin a rare glimpse into the inner workings of Europe’s ruling elite. But when The Great Terror rolled around in 1937, none of it mattered. He was arrested, sentenced and dispatched to the Gulag, callously tossed aside by the system he had served with such distinction.

Walker emphasises:

the history of the illegals offers a neat reflection of the story of Russia itself. The early programme, with its soaring ambition, its obsession with subterfuge, and its disregard for the well-being of individuals, holds up a mirror to the fiery utopianism of the early Soviet Union.

Did the Cold War really end?

These were people expected to vanish into enemy territory, sacrifice their identifies and live double lives, all in service of a revolutionary vision. But by the time the Soviet Union spluttered to an ignominious halt in 1991, that dream had long since died.

As Walker shows, most of the operatives who followed in the footsteps of Bystrolyotov were not darkly romantic infiltrators scaling embassy walls or charming secrets out of countesses. They were “sleepers” – often efficient, occasionally incompetent – blending quietly into Western cities and suburbs, awaiting a call to action that, in many cases, never came. The glitz had given way to the grind.

The Americans ends with Phillip and Elizabeth, the couple based on Bezrukov and Vavilova, gazing out across the Moscow skyline. Two weary spies coming in from the cold, they have returned to a rapidly unravelling motherland that may not understand – let alone appreciate – the sacrifices they have made in the service of its ideology.

As Walker discovered, Berzukov, when he isn’t being paid handsomely by an oil company, now lectures in international relations at one of Russia’s most prestigious universities. Vavilova, fittingly enough, now writes spy fiction.

Yet in real life, the story doesn’t end quite there. Under Putin, a former KGB officer who cut his teeth in the culture of espionage, Russia’s intelligence services have returned to the illegals programme with a renewed sense of purpose (though stripped of the ideological zeal that once propelled it).

Walker is careful not to indulge in idle speculation, but he points to compelling evidence suggesting the illegals programme has evolved rather than vanished. High-profile attacks on UK soil – including the poisoning of form spy Sergei Skripal – suggest Russian intelligence agencies remain willing to operate far beyond their national borders.

In the same breath, Walker describes what might be termed the digital turn of the illegals programme. In the place of suburban sleepers decoding radio signals, Russia has backed teams of online operatives – “troll illegals” – tasked with wrecking havoc across Western social media platforms.

These paid agents don’t gather intelligence so much as sow discord. They stoke culture wars, amplify political divisions and undermine trust in democratic institutions. Walker offers Russia’s meddling in the rancorous 2016 American election as an illustrative case in point.

In Putin’s merciless autocracy, secrecy has once again became a virtue – and the spy, far from being a dusty relic of the 20th century, is once again a symbol of national strength.

In that sense, The Illegals is not just a history of espionage. It is a timely reminder that, at least for some, the Cold War never really ended. It just burrowed deeper underground.

Alexander Howard does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.