I dip in and out, lured to new depths of surveillance data stirring on unthinkable currents. There are no limits to these domestic service files. No solid foundation to ultimately reach or push back and spring up from: just murky beginnings and slick surfaces. I navigate slowly through thousands of carefully crafted handwritten and typed letters and file notes and do my best to make sense of the chaos.

This is private, intimate reading, and these young women and girls will not let me rest. Their voices penetrate every membrane of every cell in my body until I recognise them as my own, and like proper good nannas and aunties, they are not letting me off the hook. Their apron linen is pressed against my skin, and I see their dust rise and float on shards of light. My hands are red-raw and my back aches.

This is my uncanny triggering. A persistent prickling of fine hair at the nape of my neck, all fight-flight and fury, and haunted into action.

There are generations of containment in these files. Our women and girls, our parents, grandparents and great-grandparents. The names are familiar, and my family are represented in these files too. They are all calling me back and pushing me forward and I have no choice but to respond.

Not just my family’s story

Histories of slavery, exploitation and stolen wages are considered striking features of our Aboriginal labour story from the point of first colonial contact, and an unresolved human rights issue in Australia.

The State Aboriginal Records’ “Domestic Service” files reveal the unfolding rationale for interdependent policies of child removal, institutionalisation and domestic training as important context to the burgeoning Aboriginal domestic service workforce into the 20th century.

They reveal critical voices from Protectors and mission superintendents, white employers, the parents, girls and women themselves placed into training or service. These records trigger questions about surveillance, representation and agency.

Most Aboriginal families I know in South Australia carry intimate histories of domestic service through living memory and intergenerational blood-memory passed on. We know these stories of servitude intimately within our own families and communities. They are important, often reluctantly disclosed, and held close to our bodies, leaving an indelible imprint for our future.

“They say our nation was built on the back of Blacks and it is not far from the truth,” writes Bidjara and Birri Gubba Juru historian Jackie Huggins about the decades-long “brutal history” of Aboriginal women serving as domestic servants, being “perceived as chattels and slaves”.

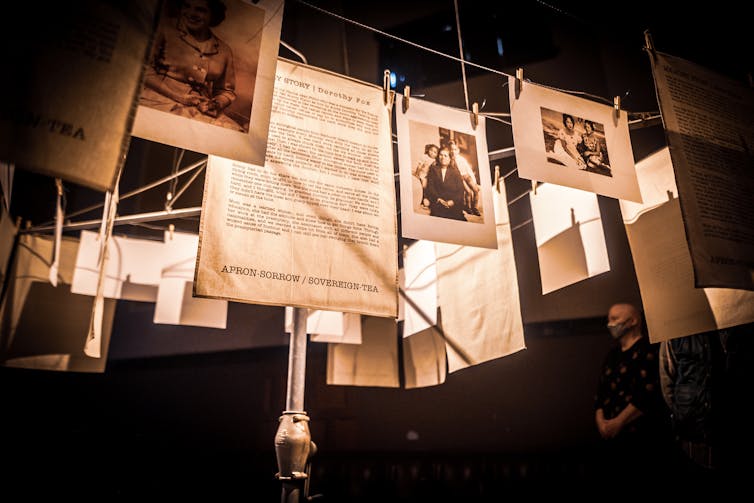

Her 1994 exhibition (with Lel Black and Leah King-Smith) exploring this history, White Aprons, Black Hands: Aboriginal Domestic Servants in Queensland, inspired my own creative research, APRON-SORROW / SOVEREIGN-TEA.

“Aboriginal people’s labour contributions are, in fact, integral to the invisible fabric of nation building,” Huggins writes. “The upkeep of white families in colonial times permitted those in power to access land and cheap labour to exploit their already scarce resources. Let us not forget the Stolen Wages.”

Despite the significance of these stories in the collective memory of Aboriginal South Australians (and Aboriginal people nationwide), the government-orchestrated system of indentured labour remains largely hidden and unacknowledged in the state’s dominant and official public narrative.

These files shone new light on my family’s story at the height of the assimilation era in the 1940s, when our women’s employment was managed by the Aborigines Protection Board and the Children’s Welfare and Public Relief Board.

I was searching for that underbelly of meaning in historical records to help me make sense of the seething, colonising backdrop to our lives. As Trawlwoolway artist Julie Gough says, we are like detectives examining the crime scene of our life.

Searching the domestic service archives

On March 13 2019, a rudimentary search through the GRG52/1 records group was conducted in South Australia’s State Records Aboriginal Information Management System (AIMS) database, using only the keyword “Domestic”.

I was then given access to 2,549 pages of correspondence letters, reports and notes generated between 1907 to 1961 through the Aborigines Department and Aborigines Protection Board. Many records were unavailable, redacted, or denied, particularly between 1947 and 1955. Many years were also entirely unaccounted for, despite the ongoing administration, management and surveillance of Aboriginal people during that time.

These missing years could signal the current limitations of the AIMS database, or that these files are unavailable because they have been lost, destroyed, or temporarily reside with another government department for research or legal professional privilege purposes.

I have selected excerpts from these files that characterise the larger domestic service story in South Australia. The only people identified are those leading state and institution administrators already on the public record for their management in Aboriginal affairs and policy history in South Australia. No Aboriginal community members or private employers are named here.

Four distinct categories of “voice” are revealed in these Domestic files, speaking to each other and intricately woven:

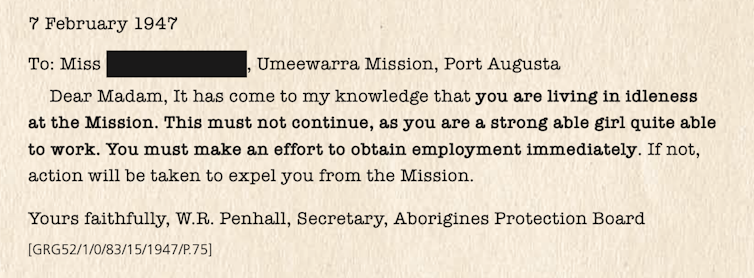

State Voices represent government and institutional control over Aboriginal girls and the punitive personal power of key agents of state, including particular Protectors, matrons, mission managers/superintendents, police constables, teachers and welfare officers.

Employer Voices represent individuals, organisations and labour schemes that liaise with the state and make requests, and report to the Aborigines Protection Board or to mission stations about what they want in a domestic worker.

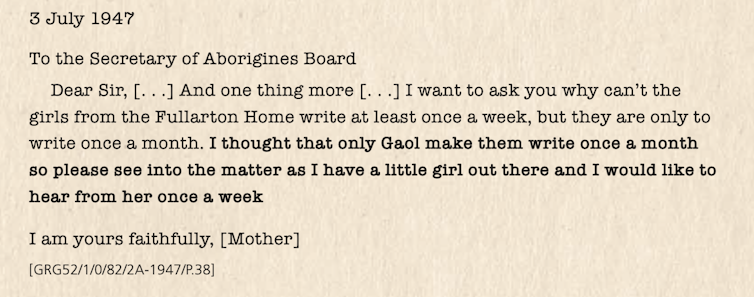

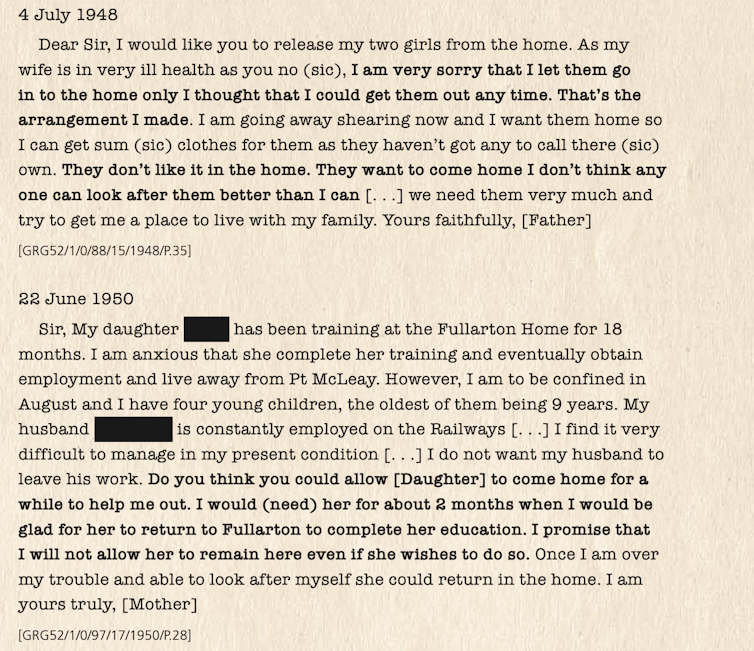

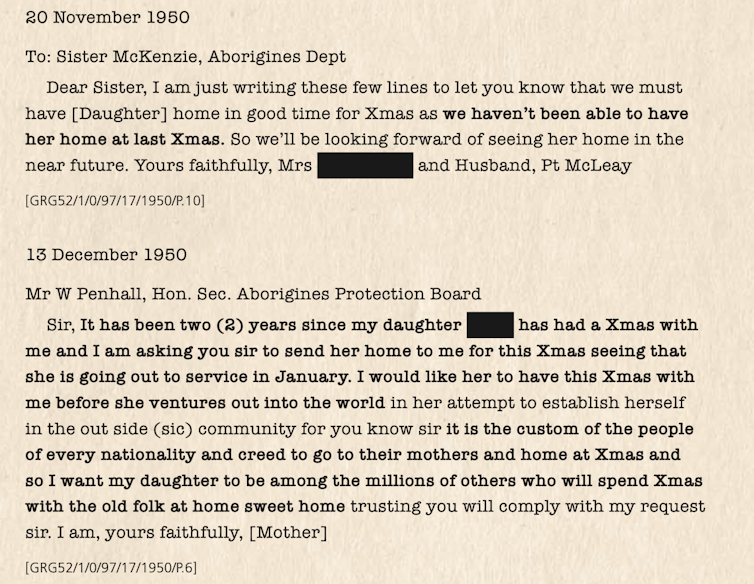

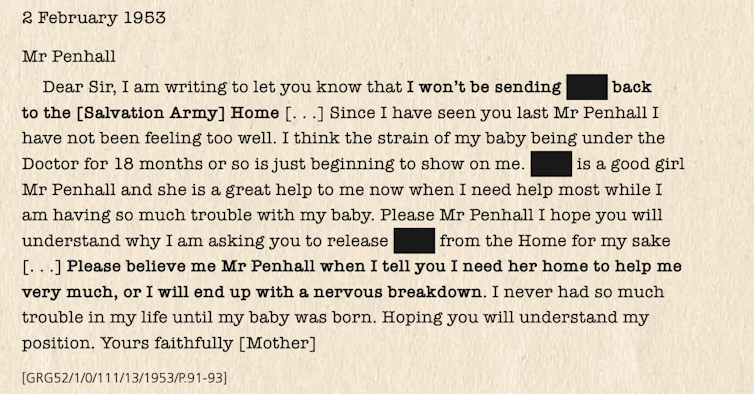

Family Voices represent parents, grandparents and other family members who write letters on behalf of the girls, or enquire after them, advocate for them and report to the state about them.

The Girls’ Voices represent the women and children who were targeted for domestic service training, or who sought employment opportunities, and wrote about their needs, conditions, and experiences.

Here, I include brief excerpts of the voices I discovered: a handful from each category.

All correspondence between a parent and child or parent and employer was mediated through the Aborigines Department and Chief Protector, and the girls often did not receive them. These letters and the people who wrote them are extraordinary, and provide a critical insight to Aboriginal agency, resistance, and strategic proactive engagement with authorities.

They demonstrate strong family bonds and prove children were not “destitute” or “neglected” by their families, as charged. I dream ways to repatriate these letters back to descendants of such powerful word-warriors, who picked up the mighty pen and wrote for our lives.

State voices: ruthless and punitive

The state’s paternalistic assumption, “we know what’s best”, is both overt and implied throughout these records. Leading public agents, administrators and managers include: the Protector of Aborigines, members of the Aborigines Protection Board, state department welfare officers in the Department of Aborigines and Children’s Welfare Board, leading figures in churches, the Salvation Army, training institutions, state homes, reforms schools and the police.

Their actions were ruthless and punitive. As wards of the state or simply as a result of being born under the Aborigines Act, girls were largely treated as gaol inmates.

These agents of state forcefully advocated for increasing measures to separate girls from their families and indenture them to domestic work, which was evident from the first 1907 Domestic Service file I accessed.

It noted that girls were unwilling to leave their homes to become domestic workers for strangers, that “special legislation” would be required to deal with them, and that parents were a hindrance to the state’s assimilation and “labour solution” agenda.

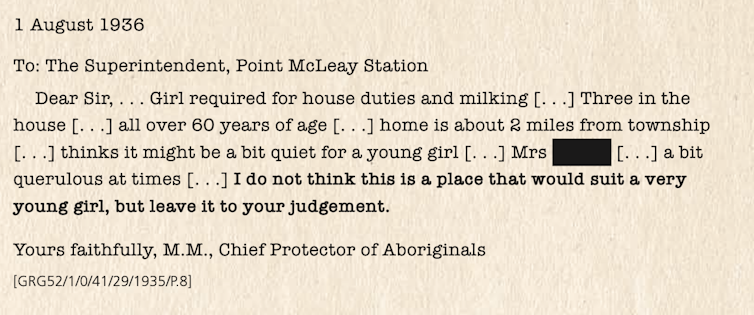

From an early age, the girls on missions were being assessed for their potential as part of the future domestic workforce. The state acknowledged that its policies and “special” measures had negative impacts on the girls and their families, and that the conditions in some workplaces weren’t ideal, but they pursued their agenda in the girls’ “best interest” regardless. The Aborigines Protection Board had the state-granted right to send the girls wherever they wanted, and chastised parents and girls if the orders given or opportunities offered were not taken up.

The “Protection Office” acted as the controlling mediator between mission superintendents, the girls’ parents, and employers in the city, towns, rural and remote locations across South Australia.

It also dealt with recruitment agencies and facilities such as: the Directorate scheme through Commonwealth Department of Labour and National Service; Woomera Village through the Commonwealth Department of Defence; the Australian Government’s war-time and post-war employment scheme “Manpower Directorate”; the Balaklava Aboriginal Welfare Institution through the Commonwealth Department of the Interior; and national pastoral companies that acted as agents for rural and remote stations.

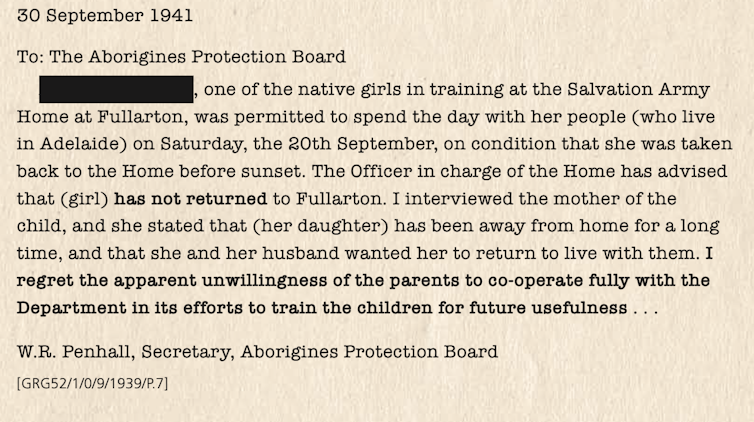

The administration was flat out responding to requests that rolled in from private homes, local farms and pastoral stations, elite private schools such as St Peters Boys and St Peters Girls, hospitals, church facilities, hotels and guest houses, and more. The Protection Office established formal labour schemes with the Salvation Army, including the Fullarton Girls Home, and managed wage schemes and the girls’ Commonwealth entitlements.

The correspondence files regarding girls in domestic training at the Salvation Army Fullarton Girls Home are substantial. Children from as young as ten years old were sent to the Home, with and without their parents’ consent.

Penhall, who was Chief Protector from 1936–1953, worked in partnership with the with the matron at the Home, Sister McKenzie, to control the girls’ movements, including their access to family. It is unclear whether this scheme was entirely legal, especially as it has been proven that Penhall acted outside the law in relation to the removal of Aboriginal children.

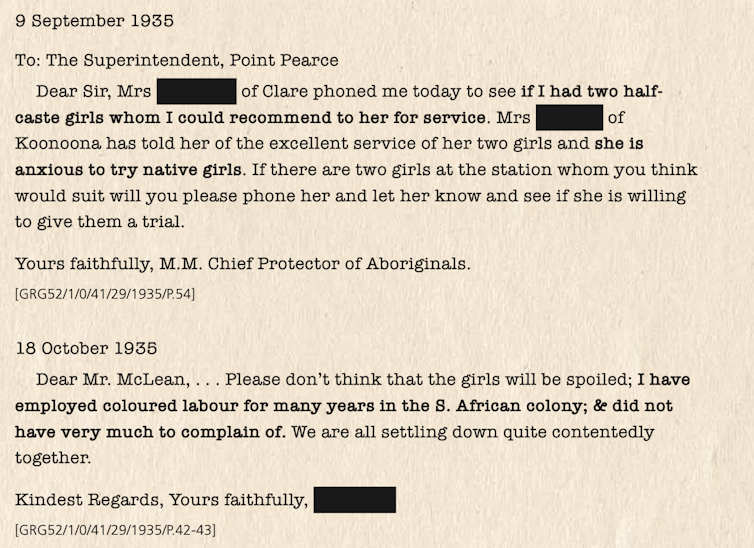

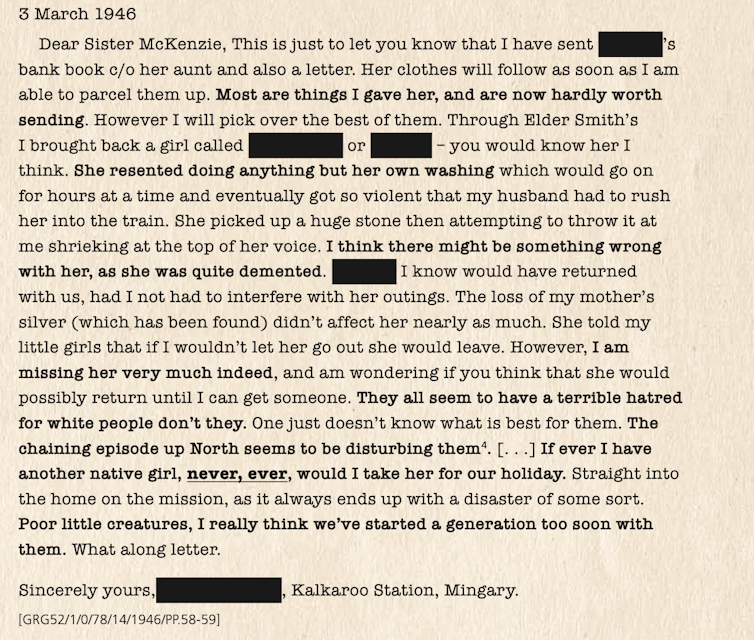

Employer voices: shocking and prescriptive

The correspondence files generated between the Protector, the Aborigines Protection Board, mission superintendents and employers are prolific and significant. They comprise mostly handwritten letters from individuals and organisations enquiring about how “to obtain a half-caste girl” for domestic help.

Their requests are at times quite shocking, desperate and prescriptive. They are forthright in identifying what they want in a worker, often referring to blood quantum, skin colour and other so-called desirable attributes.

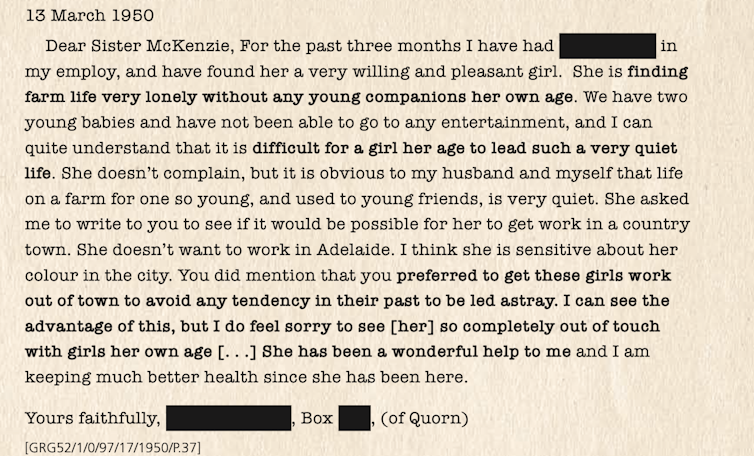

They include conditions of employment, the accommodation set-up, and what they can offer in the way of social activities and religious instruction. They report on the girls’ progress via lengthy anecdotes; complaints about their attitude and behaviour; concerns about their homesickness or parental interference; and seek advice regarding appropriate punishment measures. Some reports include praise, encouragement, positive anecdotes and updates, and indicate genuine concern about the girls’ loneliness and isolation.

Requests for Aboriginal domestic workers in private homes increased substantially during the 1940s and 1950s, and at points where “demand exceeded supply”, a standard reply was generated from the Protector’s Office along these lines: I have to advise that we have no suitable girls available for domestic work at present. Your application will be kept in mind for future reference. I will advise when a domestic help can be supplied.

In remote station homes, international pastoral companies such as Elder Smith and Dalgety and Company were effectively agents taking charge of domestic servant recruitment on behalf of their remote station managers. Dalgety and Company Ltd was registered in London in 1884 and was a major pastoral and agricultural company, or stock and station agency, in Australia and New Zealand – for more than a century.

By 1909 there was a branch in Adelaide, where the main correspondence was generated for labour matters in SA. Another key employment scheme was developed to service Woomera Village, a Department of Defence facility that was established on Kokatha Country in 1947.

The “Village” refers to the domestic area of the whole military defence complex known as the Anglo-Australian Joint Project between Australia and the UK, post-World War II. This was one of the world’s most secret allied establishments, with a rocket testing range, a high-tech aerospace and a long-range weapons development program.

It operated as a “closed town” within the broader Woomera Prohibited Area until 1983, with the usual municipal services and related jobs. This included tapping into the state Aborigines Protection Board system to acquire cheap Aboriginal domestic “help” for officers and the broader gated defence community, where my nanna, her sisters and my great-grandmother worked as domestics.

This labour procurement program is partially captured in the state records’ “Woomera, Long Range Weapons Establishment Files”.

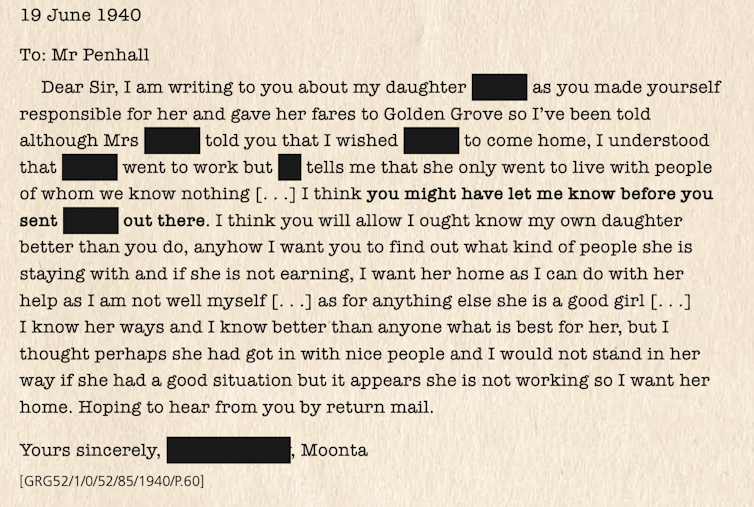

Family voices: standing their ground

The girls’ parents, grandparents and other family members entered what can only be described as a fierce postal dialogue with the state. They regularly wrote to the Protector, the matron, or the mission superintendent making enquiries about their girls, advocating for them, and seeking good working placements on their behalf.

Parents were given little, if any, information on the girls’ location and situation, and often requested details regarding the kinds of people they worked for, their working conditions, their wages, and more.

Parents had to write to the Protector requesting to see their children at Christmas, or for a weekend, or a day’s outing. Some parents had not seen their children for several years, and became very insistent in their wishes and demands which, given the Protector’s severe power over their lives, demonstrates considerable strength and courage. Despite the consequences, they stood their ground reminding the state of their parental rights, duty, and ultimate authority over their own children.

At the Fullarton Girls Home, all family correspondence was directed initially to the Protector, then the matron, then the girls. Their reply was overseen by the matron, and sometimes via the Protector. The matron was very prescriptive about outings and what time the girls could be collected and returned, with no allowance for spontaneity or flexibility.

Parents often had to travel long distances from missions, such as Point McLeay, Point Pearce and Koonibba, and organise overnight accommodation in the city so they could see their children for a short time as determined by the Protector, the matron, or private employers. The Protector controlled where they met, their activities, and discouraged them from visiting with other families living in the West End of Adelaide.

One mother wrote to Sister McKenzie refusing to return her daughter to Fullarton due to her poor treatment, stating with absolute clarity, “I think that my daughter is better in her own home”.

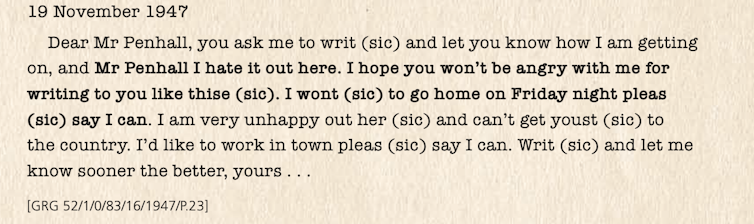

Girls’ voices: resistance and refusal

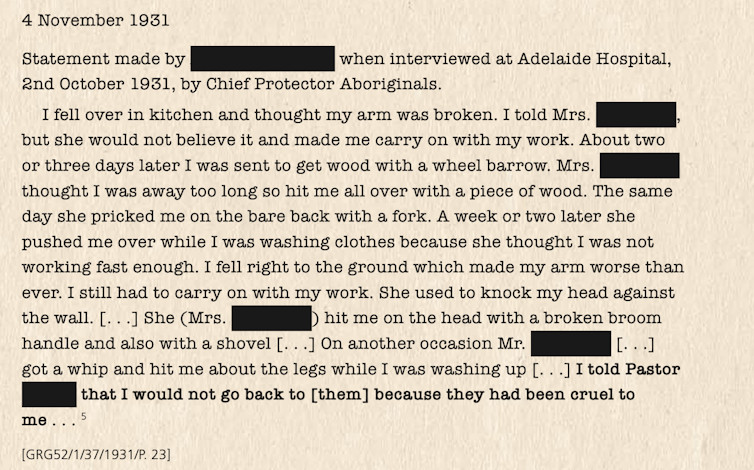

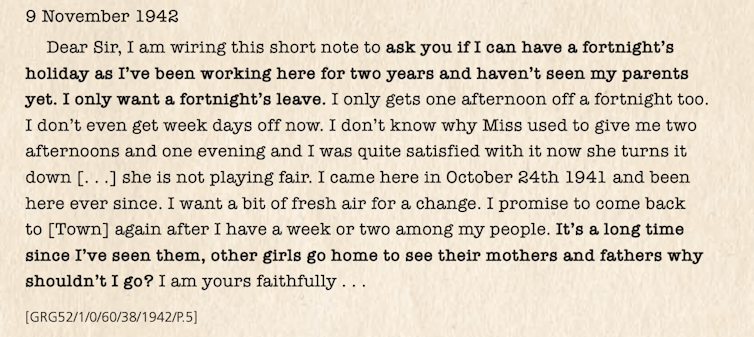

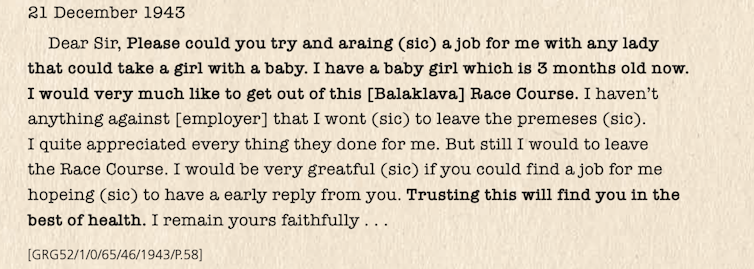

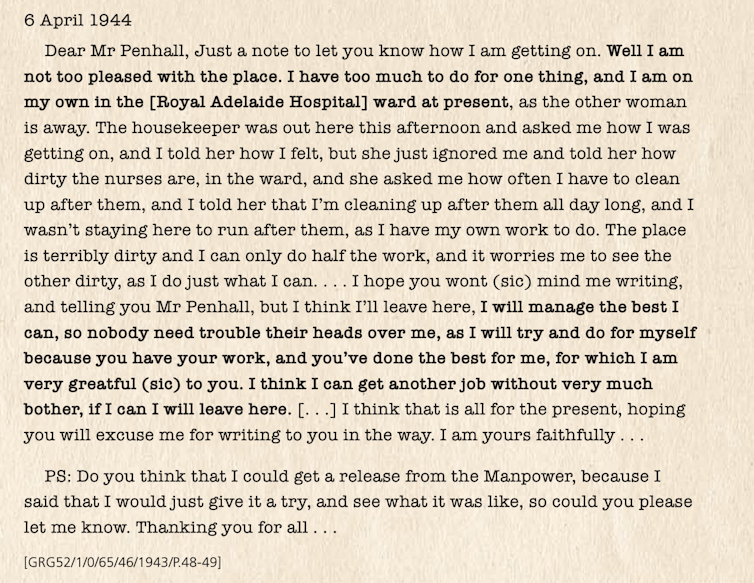

The diversity of experiences in domestic service situations are represented best in the words of women and girls themselves. Their letters to families, state authorities and employers reveal the intimate day-to-day machinations of state that controlled their lives in gendered and racialised ways. Collectively, these letters represent an accidental record on the archive to verify a much larger and hidden labour story in South Australia.

By the age of ten, girls were assessed and targeted for domestic training and placements. Some girls were indentured without choice. Some girls were highly motivated to leave the controlling confines of missions and reserves in search of the same opportunities, freedoms, and rights as the rest of society. Their individual experiences were unique and varied depending on multiple factors, such as their age, literacy levels, personalities, family supports and the attitudes of their employers and state authorities in power at the time.

Many teenage girls and young women became pregnant, and there are countless files describing the challenge of finding a work placement that would also accommodate a baby or small child. The cycle of child removal continued as babies were removed or returned to missions and reserves for grandparents to raise, before those children were themselves placed out to domestic service.

The girls clearly understood the complex policy regimes they were required to navigate and the racialised nuances of white privilege and power. Where possible, they questioned, challenged and handled the punitive actions of employers and authorities, and utilised their personal power within the limits imposed on them.

Much like the letters written by their parents, their tone was most often conciliatory, polite and gracious. They were often very direct and could often make a case to defend themselves.

For example, they responded to allegations of bad behaviour; documented mistreatment by superiors; requested work breaks and holidays (especially to see their parents); and advocated for wages owed or improved wage conditions.

They named the racism they faced and at times took matters into their own hands – despite the risk of further punishment. They absconded, eluded police, swore and raged at their employers, stole food and clothing when they ran away, ignored curfew times, and secretly met with family, friends, and lovers.

These letters are a monumental testimony to their self-determined agency, strength, courage, and resilience.

Carrying some of the weight

The emotional labour is familiar, and I am deeply conflicted; acutely aware these are not my individual records or stories to tell. So how to strike that intricate balance? How to honour the voices in the files without exploiting their experiences or sensationalising the trauma? How to hold space and do them justice?

It feels like a just and necessary responsibility. These minor intimacies are fundamental to understanding a much larger, sinister secret, and the unsettling story of South Australia. This is the archival-poetic entry point. The key is to read along and against the archive grain, to shed light on these records, interrogate their origins, and activate some awakening to reckon with it all.

And to all the girls, women and families represented here: I promise to never speak for them, to never identify them, to never presume to tell individual or family stories, and to keep talking with them so they will know … I see you. I’m listening. I will carry some of the weight of your world with only care and love and I will never let you go.

This is an edited extract from Natalie Harkin’s book, APRON-SORROW / SOVEREIGN-TEA (Wakefield Press).

Natalie Harkin receives funding from an Australian Research Council Grant, Discovery Early Career Researcher Award (ARC DECRA) DE180100559. She is a member of the State Records/State Library of South Australia Aboriginal Reference Group.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.