Vegetables unique to the Kyoto region are often called Kyo-yasai. Shishigatani squashes could be mistaken for very large decorative gourds, but they can be used in many dishes. Shogoin daikon are round like turnips even though daikon tend to be long. And as the name implies, the stripes on Ebi imo make the root vegetable look like some sort of ebi, or shrimp.

Another factor that sets Kyo-yasai apart is their size -- they're often big. Many are considerably larger than their equivalents in other parts of the country.

But Kyoto is not the only place with its own distinct category of vegetables; unique varities can be found in almost every area of the nation. Osaka Prefecture has its Naniwa vegetables, and Tokyo has the Edo category, which carries the old name of the capital.

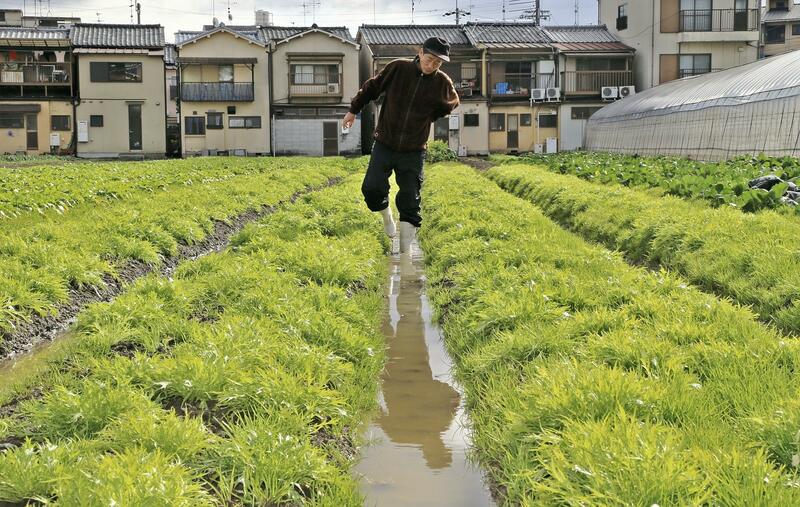

Historically, vegetables were usually grown in the suburbs of major cities, but with technological innovation, scientific experimentation and improved breeding techniques, higher-yielding varieties resistant to disease and pests have been developed one after another. Such practices, however, have led to the demise of many distinct and traditional varieties.

The production of Kyoto vegetables also declined at one point, as more and more people turned away from traditional food and instead opted for Western cooking at home.

The consumption of Kyo-yasai was dealt another blow during the second half of the 20th century, with a rise in the number of smaller households. Many people came to see the large vegetables as simply too big for their families to eat.

However, thanks to branding, Kyoto vegetables made a comeback. The prefectural government promoted about 20 varieties in the Tokyo metropolitan area and other areas under the name "Kyoto Brand Products." When word spread about pricey Kyo-yasai being sold in Tokyo's chic department stores, people back in Kyoto began to take notice of the respect given to their local produce.

It is said that tradition is comprised of history and stories, and that a bizarre product can become prized if there are some stories and a bit of history behind it. And the people of Kyoto are renowned for their ability to add such elements.

Surprisingly, most Kyoto vegetables can be traced back to other regions. Many of them were brought to Kyoto as offerings to temples, shrines and the Imperial court. These vegetables were then given to farmers in the surrounding areas. Although there may have been differences in the climate and soil, the farmers made the effort to produce high-quality vegetables to be used as ingredients in Kyoto's very delicate culinary practices. As a result, such vegetables eventually branched off from their original roots and became their own distinct varieties.

Initially, the skin of the Shishigatani squash bore some resemblance to the petal patterns on a chrysanthemum. During the Bunka era (1804-1818) of the Edo period (1603-1867), its seeds were brought from Tsugaru, now Aomori Prefecture, to Shishigatani, present-day Sakyo Ward, Kyoto. A farmer in Shishigatani started cultivating the seeds and the round squashes somehow became gourd-shaped. The seeds are found only in the lower bulb of the vegetable, and the edible part grew to be 1-1/2 times larger than in the original variety.

The round Shogoin daikon was originally long and thin. During the Bunsei era (1818-1830), the daikon was gifted from Owari Province, now Aichi Prefecture, to Konkai-Komyoji temple in Sakyo Ward and was provided to farmers living near the Shogoin temple. As the farmers only selected seeds from radishes that were appealing in shape as well as flavor, the long radishes eventually became round. Further anecdotal evidence suggests that since the fields in this area had a shallow layer of soft soil, it encouraged the planted daikon seeds to grow horizontally.

Toyotomi Hideyoshi, the 16th-century warlord who took control of the nation, built a castle in Kyoto, called Jurakudai. After the castle was destroyed, unusually thick burdock was said to have grown in the moat, which was used as a garbage dump. This is now called Horikawa burdock.

"We don't necessarily try to use Kyoto vegetables, but they are all good quality and have distinctive features. So we end up using many kinds of them," Takuji Takahashi, the third-generation owner of Kinobu, a Kyoto-style cuisine restaurant in Shimogyo Ward, once told my colleague during an interview. "Even simply boiling the vegetables can slightly affect how they taste as well as their aroma."

Read more from The Japan News at https://japannews.yomiuri.co.jp/