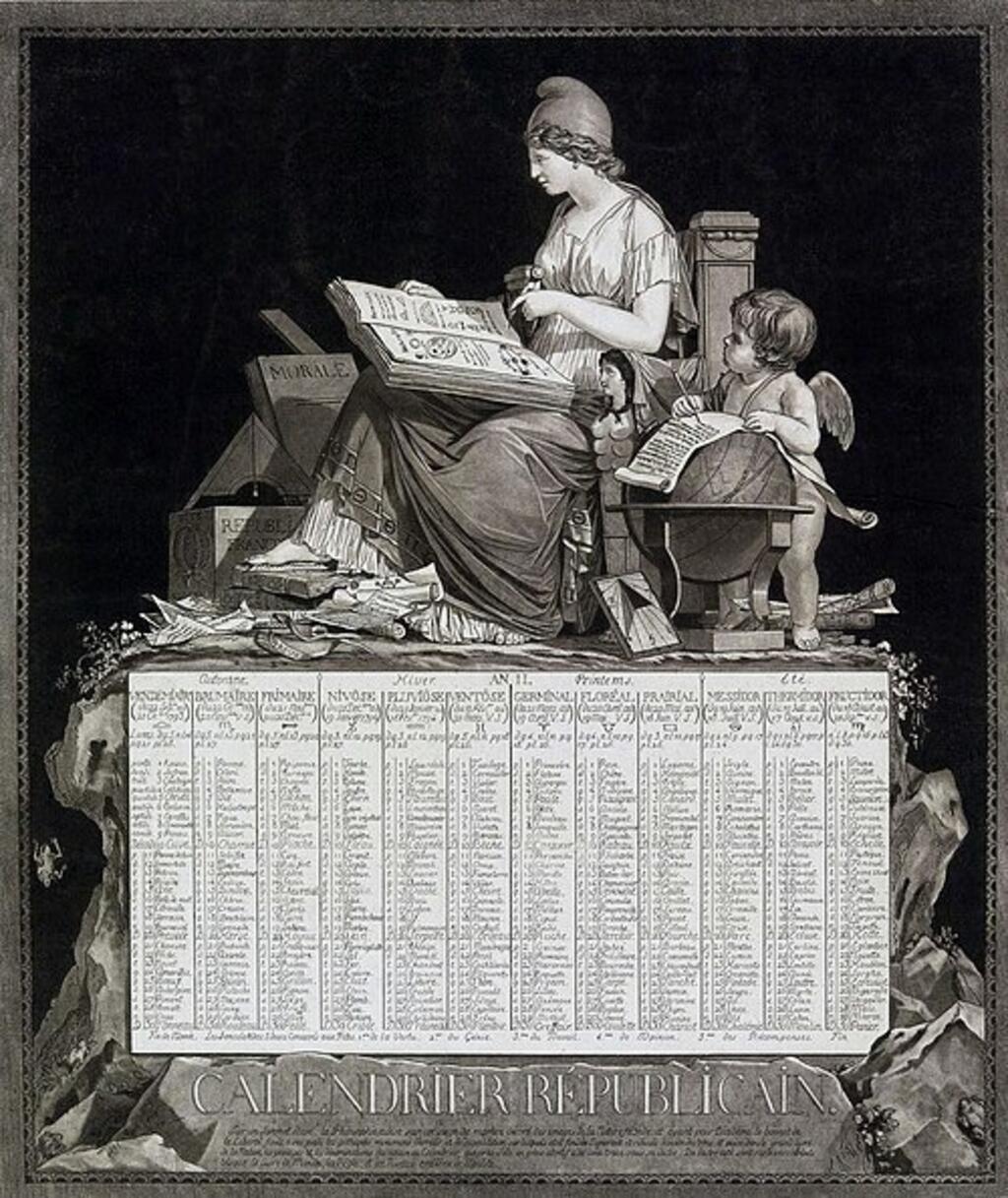

When France founded a new republic, 233 years ago this week, it opened a new era – literally. For a brief period the country ran on a unique calendar, designed to liberate the people from religious customs – until it became clear that time and date would not be overthrown.

Republican time began on 22 September, 1792. Gone were the eras BC and AD – the new France needed a new calendar, one that no longer counted years from the birth of Jesus or was paced by Christian holidays.

It was the first day of the "era of liberty".

One of the most ambitious reforms of the Revolution, it would also prove to be one of the shortest lived.

Symbolic beginnings

People had been talking about an epochal shift since the storming of the Bastille in July 1789, but it took another three years for legislators to found the First Republic, and a year after that to switch to the Republican calendar.

Adopted on 5 October, 1793, it was backdated to begin the day after the proclamation of the Republic – which, by coincidence, was also the day of that year's autumn equinox.

The committee of politicians, mathematicians, astronomers and geographers tasked with designing the new calendar latched on to the symbolism of day and night reaching equal lengths, just as equality was being enshrined as the founding value of the new Republic.

They declared the new year would begin on every autumn equinox from then on.

La Bastille - medieval symbol of oppression, modern symbol of liberty

Making a decimal point

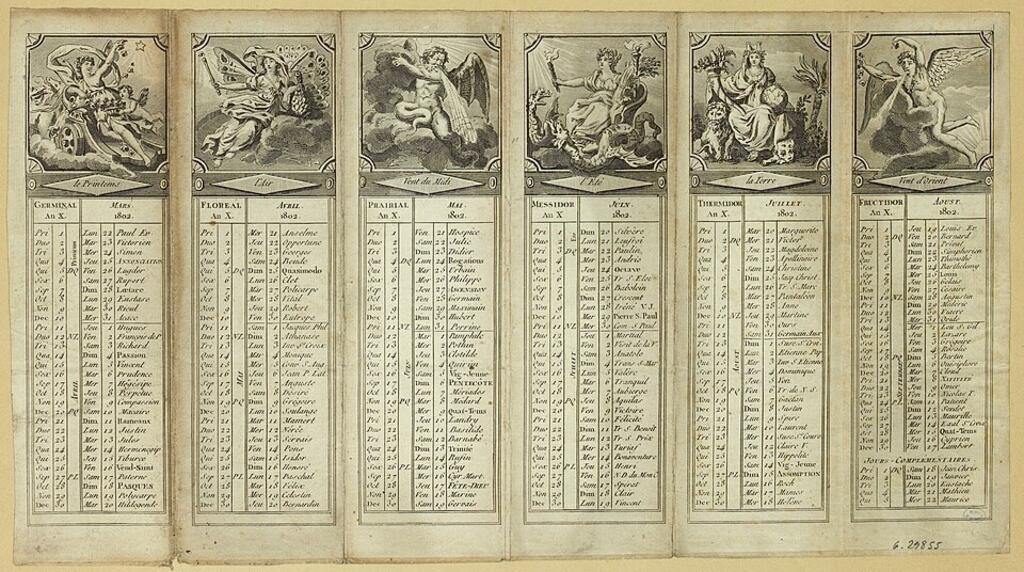

A Republican year measured the same as those before it – 365 days, or 366 in leap years – divided into 12 months.

But its months all had 30 days, followed by five to six days at the end of the year making up the difference. Each month was split into three blocks of 10 days that replaced the seven-day week, dubbed décades.

Days were named sequentially: a décade started with primidi ("first day") and ended with décadi ("tenth day"), the designated day of rest.

It chimed with a broader quest for more "rational" ways of measuring. The same era saw France adopt the metric system and a decimal currency, the franc.

The Metre Convention: a milestone that's changed modern life immeasurably

It even attempted to decimalise the days themselves. Along with the Republican calendar came decimal time, which divides days into 10 hours instead of 24. Each hour lasts 100 minutes and each minute 100 seconds.

The change didn't stick. It was mandatory on official documents for a few months, but the majority of the population never changed their clocks.

The natural world

The Republican calendar wasn't all logic. Poet Fabre d'Eglantine was responsible for naming the new dates, and he sought to put the natural world at their heart.

Months were named for the season's weather and crops, with the year starting in autumn in Vendémiaire (from vendange, the grape harvest) and ending in summer in Fructidor (fruit).

In winter, Nivôse (snow) gave way to Pluviôse (rain), and in spring Germinal (germination) was followed by Floréal (flowers).

Fabre d'Eglantine also replaced the calendar of saints with an almanac of "objects that make up the true riches of the nation" – flowers, fruits, trees, animals and farm tools.

The first day of the Republican year, 1 Vendémiaire, was the day of grapes. The days that followed honoured chestnuts, horses, carrots and parsnips.

"As the calendar is something that we use so often, we must take advantage of this frequency of use to put elementary notions of agriculture before the people – to show the richness of nature, to make them love the fields," wrote Fabre d'Eglantine in his report to legislators.

This too was typical of the age. Nature took on the weight of a religion during the Revolutionary period, according to historian Julien Vincent of Panthéon-Sorbonne University.

"Nature became a value – not only financial, but also religious and moral," he told RFI.

Loss of holidays

The loss of the Christian calendar, though, left a gap nothing could fill: holidays.

People now had to work nine days in a row before getting a day off, and since the break was no longer necessarily a Sunday, many workers found themselves unable to go to church.

Instead of more than a dozen religious holidays scattered throughout the year, the only official celebrations were a handful of memorable dates from the Revolution.

There were also the five or six bonus days clustered at the end of the year, and dedicated to wholesome Republican values such as virtue, labour and reason.

The summer France got its first paid leave and learned to holiday

People resented the upending of centuries-old cycles of work, rest and worship.

While, at first, authorities vigorously tried to enforce the Republican calendar, even to the point of forbidding newspapers from giving the "old" date alongside the new, within a few years the public and politicians alike were lamenting the loss of the old ways.

Critics pointed out that starting the year on the autumn equinox, which varies each year, threw off the calculation of leap years.

Meanwhile, the natural rhythms the calendar supposedly tapped into belonged only to the north of mainland France, leaving warmer parts of the country perpetually out of synch.

And most inconveniently of all, the system put France on a different calendar to the rest of the world.

How Republican time ran out

When Napoleon Bonaparte took power in 1799, it was the beginning of the end for Republican time.

After he allowed the church to regain some of its former sway, the Republic did away with the 10-day week so that workers could once more take Sundays off. Then four Christian holidays were reinstated.

Soon the new calendar was just a formality, an extra line on official documents. On 9 September, 1805, little more than 12 years after it was introduced, the Republican calendar was officially retired.

It would return under the short-lived Paris Commune insurrection of 1871 – for all of 18 days. Since then, few have argued for reviving it, although it turns up occasionally on novelty calendars or anarchist newsletters.

But in the main the Republican calendar serves merely as a reminder of the limits of reform: there's only so much you can overthrow, even in revolutionary France.