This story is pretty long, but it’s written in short chunks, so don’t worry about it, you’ll be fine. You can check your Instagram every 300 words or so, whatever.

Even if you’ve never heard of Flesh For Lulu, you might like it. It has bits about boozing and drugs and there are a couple of fights (including a brawl with John Lydon), and stuff about gangsters, goth and a ghost.

There’s an actual sword fight between Sisters Of Mercy singer Andrew Eldritch and Flesh For Lulu guitarist Rocco. It’s a story about friends – about how friends fall in and out of love – and about ambition and business and how things that should work out still don’t, sometimes. And it contains two stories about sudden illness, one of which ends in death.

On the morning of Nick Marsh’s funeral, James Mitchell dropped his kids off at school and drove across London to the service in Epping Forest where he met Lulu, the woman who gave her name to the band Mitchell had formed with Marsh, aged 19: Flesh For Lulu.

That same morning, Kevin Mills – the man who played bass, wrote songs and managed Flesh For Lulu for most of their career – put an out-of-office message on his Pet Taxi business, got in his car and drove across town alone.

In Notting Hill, guitarist Rocco Barker took a handful of valium and drank Guinness all morning. “Just to get me through it,” he says. “I don’t remember anyone from the funeral. I was just in a haze.”

It was hot. In different circumstances, you would have said it was a beautiful day. Jets from nearby North Weald Airfield roared across the sky. To a lot of the people crowding outside the building – because Nick Marsh’s final show was sold-out – it seemed triumphant, like Nick was getting his own military salute.

The service was long and touching. Two of Nick’s friends sang If You Go Away, a Jacques Brel song that was covered by Scott Walker and Frank Sinatra and 21 past and present members of the Mediaeval Baebes sang together around his coffin. Afterwards, The Urban Voodoo Machine – the band Nick had played in for a decade or so – formed a New Orleans-style marching band and led the procession into the trees to the mournful sounds of St James Infirmary.

At the graveside, Nick’s young daughters, bid him goodbye. “When I come back in a year, daddy,” said one, “you’ll be a beautiful tree and we can play together.”

So there you go. That’s all the major characters and, yes, Nick dies in the end. This story does not have a happy ending.

I was supposed to write this a couple of years ago but I messed up. I interviewed Nick’s wife Katherine – the week before his funeral – and then lost the recording. I took notes at the funeral and then lost the notebook. I was asked and tried to make a Wikipedia page for Nick but Wiki’s editors wouldn’t approve it.

Nick, they said, was not ‘notable’ enough – his life, they felt, was covered in the Wiki entry on Flesh For Lulu.

Then I lost Katherine’s interview and gave up.

So this is me trying to make amends. This is the story – not of Nick, but of Flesh For Lulu. I spoke to all four core members and many of the others.

It’s the story of a band. And it begins with a funeral and ends with Nick Marsh taking the piss out of my trousers.

James knew Lulu way before he’d met the rest of them. He’d shared a flat with her, his first flat in London after moving down from Scotland. It was mad: Lulu lived on the landing with her boyfriend; another guy lived in the flat’s tiny attic. Later, not long after the band had started, Lulu was standing in front of a poster for the Andy Warhol movie Flesh For Frankenstein and, bang, they had a name.

James had moved from Scotland to London to study drama and was in some terrible punk band. One day his mate told him about this guy he’d met at a party who was getting a band together. For some reason – and James still doesn't know what possessed him – he decided to go down to Brixton with his guitar to meet this guy.

When he got there, Nick Marsh didn’t need a guitarist, he needed a drummer. Even though he’d never played drums, James got behind a borrowed kit, played a couple of bits and Nick said, “OK, let’s do it.”

The two men came from completely different backgrounds. James came from a relatively comfortable background in Linlithgow and Nick had lived for three years in a community housing project ("Experimental for the time," says his mum, Pat) on the edges of London. But they had music in common – punk, Bowie, Alice Cooper, but also older stuff like Sinatra and Scott Walker – plus James had written a bunch of songs and was a handsome bastard, just like Nick.

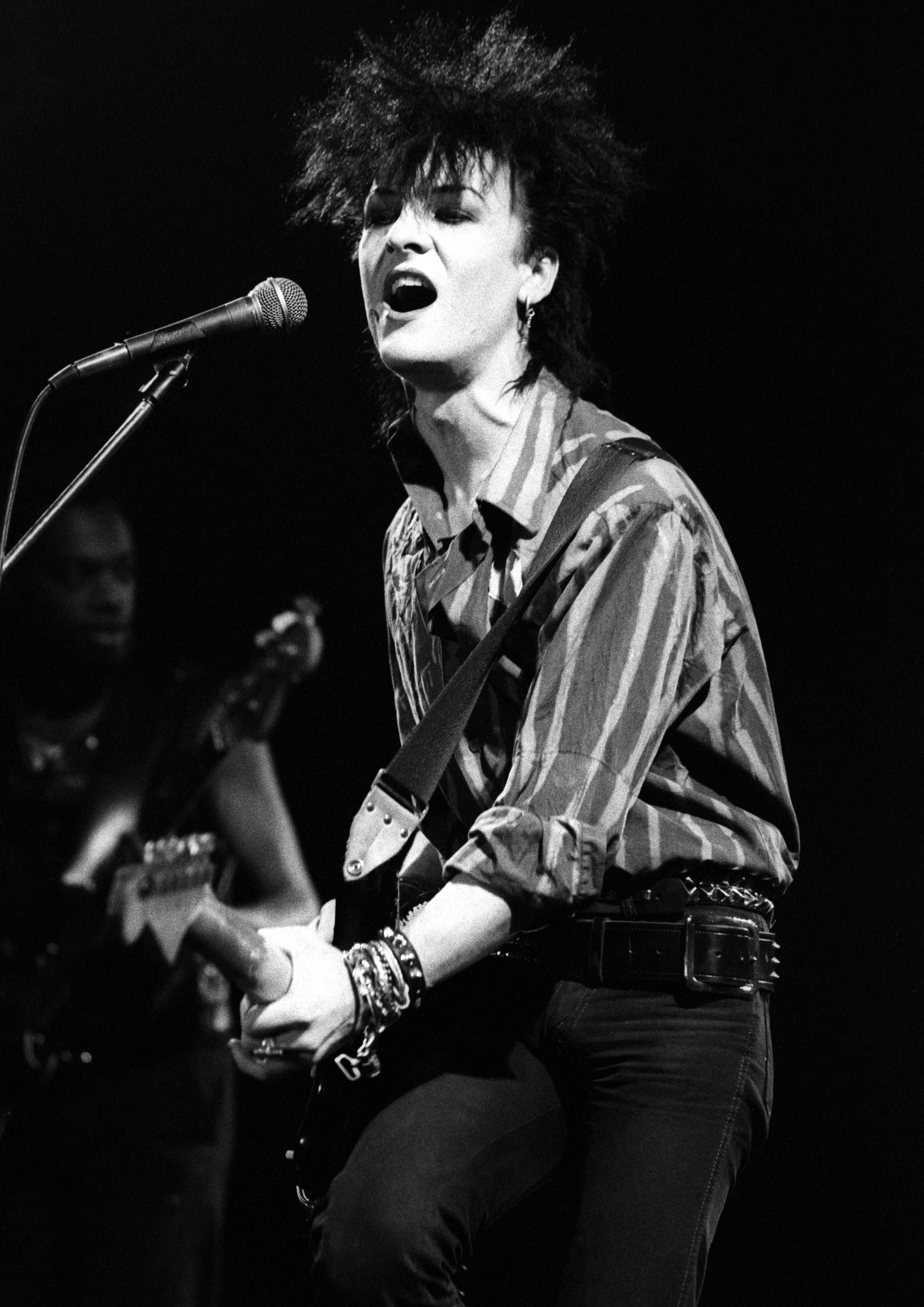

Nick was charming, charismatic and no slouch on guitar, either. And then there was his singing.

“He had an absolutely amazing voice,” says James. “You heard his voice and his playing and that was something none of us could do. That was what made me drop out of university. When I first met him, it was almost like an instant love affair. I think it was the same for Kev and Rocco too. Rocco says he had to join us because he had to pay back his dealer and all of that – but it was Nick. He was just a lovely guy.”

When Rocco Barker was 15, his art teacher, a young guy from Yorkshire, invited him to a party after school. They had bonded over records by Alice Cooper, Van Der Graaf Generator and Iron Butterfly.

At the party, Rocco got talking to this guy in a wheelchair, an old biker who’d had an accident or something, and he asked Rocco to follow him into a bedroom.

But don’t worry, it’s not that kind of story. In the bedroom was a record player. “I want you to listen to this,” the old biker said and he chopped out a line of speed. “But before that, snort this.”

Rocco snorted the line of speed. And the biker turned the stereo up, lifted the needle and put on White Light, White Heat.

"And my fucking world went mental," saays Rocco. "I went ‘Fuuuuuck!’ That was it.”

When he was 13, Nick’s mum ran a stall down Camden Market, back when the market was just half a dozen tables. There was always a busker down there – an old hippy type – and this gave Nick an idea. He could busk. After all, he had a guitar and he knew Blowin’ In The Wind and Ziggy Stardust.

So one Saturday he gets down there early, gets his hat on the ground and is strumming away when the old hippy guy appears.

He comes over and eyes Nick-the-Kid up. “How long do you think you’ll be here?” he says.

Nick shrugs. “I dunno. Til I’ve got 50p?” he says.

The hippy puts his hand in his pocket and throws a coin at him. “Here’s 50p,” he says. “Now fuck off.”

A couple of years later, Nick’s at his first ever Clash gig: the Rock Against Racism rally at Victoria Park, April 1978. He’s standing right at the front and can’t believe his fucking eyes: “I know that geezer!” he shouted to anyone who’d listen. “I know that geezer!’”

The old hippy was fronting his new favourite band. He was Joe Strummer.

For a while, Flesh were a three-piece: Nick, James and Glen Bishop on bass. It was the time of Simple Minds and Haircut 100, and their demos were a bit Minds-y, a bit Depeche Mode and Talking Heads: white-boys-do-disco, with crisp Nile Rodgers guitars and nagging keyboard hooks.

They got a John Peel session and from that Polydor paid for them to do some demos and then quickly signed James and Nick up as the next Thompson Twins or some shit.

Yeah, good luck with that.

Nick had rock’n’roll in his bones. He once told James that when he was a kid the only rule was “do whatever you want”. (His mum, Pat, messaged me when this article was first published, worrying that I'd made this sound a bit "Aleister Crowley." "He was only told 'do what you want' in relation to the career in rock that we always knew he'd have," she said.)

James remembers him going from one squat to the next, one girlfriend to another, or helping him do moonlight flits to get Nick out of places where he owed the landlord a ton of money. Even after the Polydor deal, he didn’t want to spend his money on trivial things like rent.

“He ended up going down to this place that doesn't exist any more,” says James. “This place called Gypsy Hill in Crystal Palace. It was a whole tribe of squats, infamous in its day. We did some of our early gigs there, but it was quite rough – full of crusties and bikers.

“The first gig we did was at my university, and we had this whole crowd from Gypsy Hill there and that’s where the make-up thing happened.” The girls from Gypsy Hill took it upon themselves to give the young Flesh a gothic make-over. It became part of the stage show.

By 1983, Rocco Barker was a minor league star. His band Wasted Youth were the talk of the music weeklies and looked like they could be big – if they stayed alive long enough.

“I was on the front cover of Sounds and I couldn’t even play guitar, to be honest with you,” says Rocco. “I could literally only string a few chords together. That band was all non-musicians. We were part of that whole art mentality where we didn't give a fuck. We had a guy eating sandwiches with a lightbulb over his head and a vacuum cleaner while we all played one chord. And people just loved it! It was that kind of pretension that we were into, more than rock’n’roll.”

They worked with Martin Hannett and were produced by Peter Perrett of The Only Ones. By the time of their last gig at London’s Lyceum Ballroom, the whole band were heroin addicts. When they split, Rocco urgently needed a gig.

“I needed money to keep my habit going. I was at my dealer’s house and he’d cut out this thing from Melody Maker and handed it to me. He was like, ‘Look: fucking pay me the money you owe me – get yourself a bloody job!’ So he handed it to me and it said ‘Guitarist wanted. Lou Reed and the Velvets, Iggy Pop & The Stooges and the Banshees’.”

Rocco rang the number in the ad, spoke to Peter Webber, the manager, and went down to audition. “I don’t think I was out of it,” he says, “but I wasn't full of enthusiasm or anything. I don't think my guitar had more than two strings on it, so I had to borrow a guitar. I probably played way out of tune and Nick had to tune me up, but I was actually pleasantly surprised. I really liked it. I thought, ‘Wow – this could be good.’”

In 2015, just months before he died, Marsh told me this same story. “He turned up with, like, a borrowed guitar, and he was nodding out in the audition,” he said. “And everyone else was like, ‘You don’t want that guy in the band, do you? He’s a junkie!’”

But Nick saw something else. It became his personal mission to get Rocco away from all that. The band went on tour in Norway because they heard there was no junk there, and no way of getting it, and Rocco went cold turkey in the back of the van. “I had to hold on to this shivering, gibbering wreck for a couple of weeks,” said Nick. “But he meant it when he said he wanted to get away from it – he never did go back.”

“Within a year I was clean,” says Rocco. “I’d been on methadone and that didn’t work, but by pure coincidence, at the same time as joining Flesh For Lulu, I left my girlfriend that I’d been with for six years, since school. You kind of have to do that. I couldn't go back to where I lived because of the whole association thing. I managed to sever all my ties and almost start a new life.”

He started going out with someone who wasn't into heroin. Her parents were doctors and they recognised Rocco’s addiction and set about helping him. “Anthony, her dad – it was was unbelievable the way he helped me. So I had that support.”

James hadn’t seen anything like that before. Even Nick, raised on a commune, was still a bit naive. Rocco, on the other hand, was pure East End. Later, when they were touring America and people would say, “Hey man, where you from?” Rocco would say, “I’m from London. But I’m not from just any part of London. I was born in a place called West Ham. Plaistow. Canning Town. If you imagine the arsehole of London, the sphincter – where all the shit comes out – that’s where I was born…”

“In the East End you were either a junkie or a gangster,” says James. “I remember going to a pub with Rocco and I’d had a spot of bother with someone and this little guy comes up, Rocco’s Uncle Charlie, who’s on the run after some shooting up in Birmingham, and he’s like, ‘Roc tells me you're in a spot of bother – do you want me to sort him out?’ I’m like [timid, polite voice], ‘No, it’s OK, Uncle Charlie’.”

Later, back at Rocco’s house, Rocco, his dad and his brothers were all completely pissed. James, being a nice middle class boy, made conversation with Rocco’s Italian mum, and tucked into the huge Sunday lunch she’d put on. He was the only person who ate a thing.

It was a pattern he’d see repeated on countless tours: “I would be trying to keep up appearances while the rest were all badly behaved.”

I tried to do some digging on Rocco’s Uncle Charlie, Googling phrases like ‘Charlie Barker east end gangs’ and so on. The most common result I got was for Charlie Richardson.

Charlie and his brother Eddie ran The Richardson Gang. According to Wikipedia, the Richardsons “were an English crime gang based in South London, England, in the 1960s. Also known as the ‘Torture Gang’, they had a reputation as some of London's most sadistic gangsters. Their alleged specialities included pulling teeth out using pliers, cutting off toes using bolt cutters and nailing victims to the floor using 6-inch nails.”

Serving a 25 year sentence, Charlie went on the run from an open prison in 1980. He was captured soon enough, but by 1983 he was out on day release and a free man by ’84.

I emailed Rocco. “I’ve got a crazy question,” I said. “Your Uncle Charlie – he wasn't Charlie Richardson, was he?”

Rocco got back that same day: “He was part of the Richardsons at one point,” he said, “but no. He was a lone wolf, so to speak.”

Either way, it might go some way to explain Flesh For Lulu’s darker lyrics – all those references to guns and threats and broken bones (‘Come on, open the door/I swear I won’t hit you no more’).

Everything happens after dark.

So now it was Nick, James, Rocco and Glen Bishop. The music had started to change. Rocco had brought a level of white noise and rock’n’roll abandon to the Flesh For Lulu sound and you could hear it on their first record, the Roman Candle EP.

Written by Nick, Roman Candle sounded like Lou Reed arranged by Ennio Morricone and played by Adam and the Ants – all twanging guitars and chain gang backing vocals. Coming Down was sexy, woozy psychedelia (‘My lips turned blue when I kissed you’), written by James and inspired by Coming Down Again from the Stones’ Goats Head Soup. Lame Train was the first sign that they could carry a pop hook, but it still sounded like a message to Polydor: ‘Where your train is going, I don’t wanna go…’

Polydor were horrified. A&R guy Alan Sizer was furious. They’d signed a pop duo and got a record from some dirty fucking rock band! To add insult to injury, Roman Candle actually did decent business and got good reviews, so if the label just dropped them, they’d look like dicks. Polydor were not happy with this unexpected success, not one bit.

I wrote and edited this by myself, so there’s only me to blame. I didn’t get paid for writing it, so word count wasn’t an issue. It wasn’t commissioned and I didn’t have a deadline. I did all the research, and interviews and and transcribed them all, except one.

My friend Lianne transcribed the Kevin Mills interview and it drove her mad. In her notes she wrote, like the pro she is, “The interview was difficult to transcribe at times because Kevin sometimes tails off at the end of his sentences. He also has a tendency to mumble slightly. When recalling funny events, Kevin tends to laugh and talk at the same time, and is also eating during the interview, which makes the dialogue harder to decipher.”

I interviewed Kevin by himself in some pub near his house. His dog Cookie – a Parsons Jack Russell – was there and, frequently, we both talk to it too. I spoke to James and Rocco together and then separately; Rocco in his workshop in Westbourne Park and James at a tapas bar in Ladbroke Grove.

The Nick Marsh interview most quoted in this piece is from 2005. I interviewed Nick maybe three times in total and 2005 was the first time. We met during the day in Bar Italia in Soho. The interview was recorded on a C90 tape and the recording is a nightmare: full of background noise, music, and the clatter of cups on saucers.

Lianne would’ve hated transcribing that one.

Kevin Mills first met Flesh For Lulu at The Batcave, the club night he used to run as part of Specimen. Specimen had been formed in Bristol and moved to London to seek fame or infamy. After their first gig at Dingwalls, the venue banned them.

“We trashed the mic stand or something like that,” says Kevin. “They were like, ‘You will never work at Dingwalls again!’ and we were like, ‘Thank God for that, it’s a shithole.’”

Unable to get a gig, singer Ollie had a brainwave: they would get their own club and play anytime they wanted. Ollie went to see this old dude Maurice, who ran a burlesque strip club above Gossips, just off of Dean Street in the heart of Soho, back when Soho was Soho, and Maurice said, “Well, I’ll give you one night: if you can fill it, you can have it every Wednesday.”

So, they did. They stuffed the place full of all kinds of crazy people and the Batcave was up and running.

In no time, it out-grew Maurice’s strip club and became one of the biggest club nights in London. It was the Ground Zero of Goth and the money from the Batcave bank-rolled the whole Specimen operation.

“In the 80s there was a real tendency for mid-week clubs,” says Kevin. “Weekends were for the ‘bridge and tunnel people’, you know, all the people who came in from Essex and Hertfordshire to go to The Hippodrome or something. The cool cats went out in the middle of the week.”

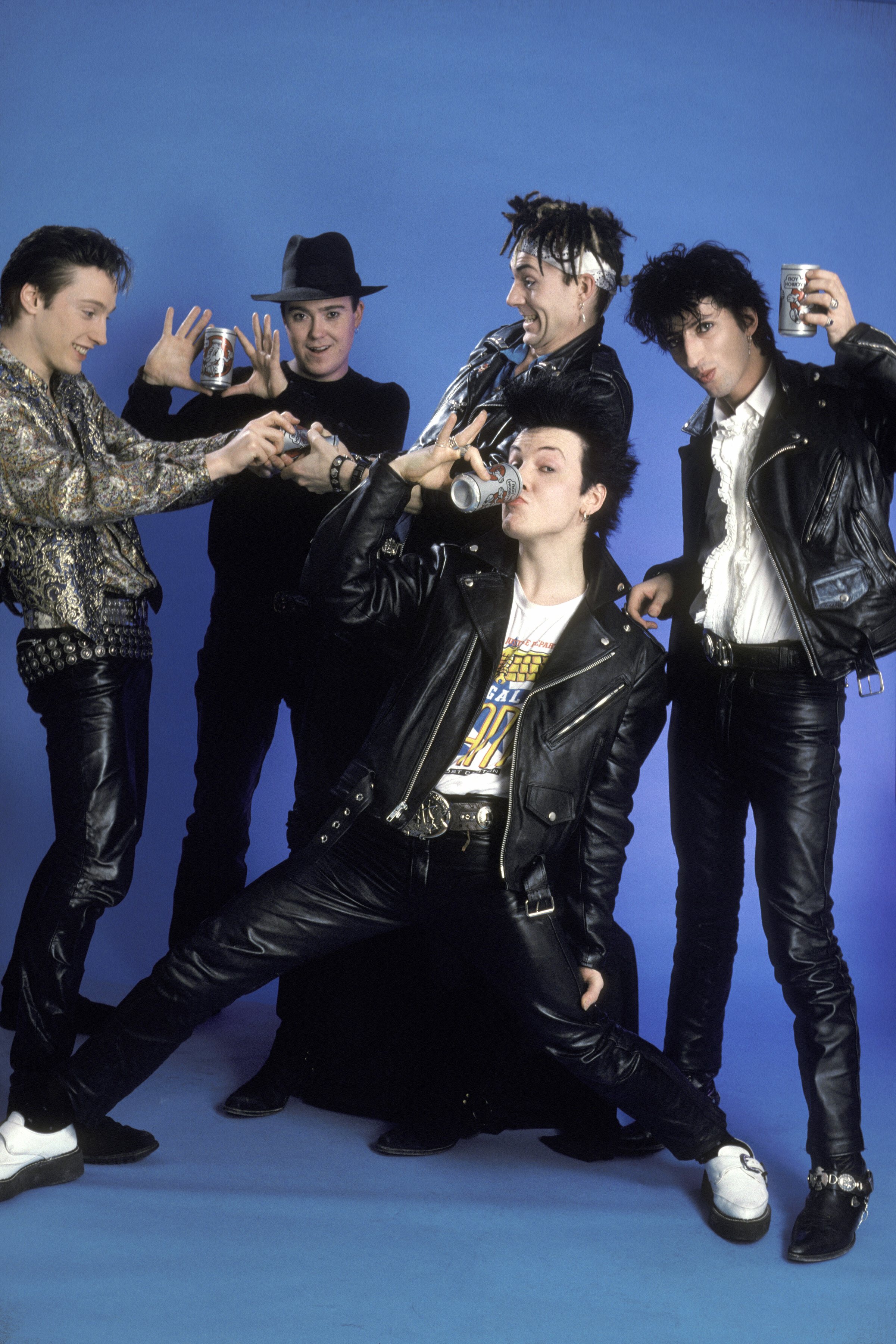

It was 1983-84 – the ‘goth movement’ hadn’t really been invented. “Everybody goes, ‘Oh yeah, Flesh For Lulu: goth band,’” says Kevin, “but goth wasn’t really a look then. Flesh For Lulu were really a rock’n’roll band with big hair. Loads of jewellery and make up and stuff, but essentially a rock band with punk influences and lots more – a lot of soul and country. All kinds, really.”

One day Nick picked up a pair of his girlfriend’s fishnet tights, tore a hole in the gusset and put his head through it, stuck his arms into the legs and was like, “Hey, how’d you like my new look?” Everyone pissed themselves so, for a laugh, he goes down the Batcave dressed like that.

Siouxsie Sioux was there. Three days later, she’s on Top of The Pops wearing Nick’s look. “She totally copped that off me, man,” said Nick. “And now goths around the world are dressed like that. That’s my claim to fame – it’s more of a claim than being in the fucking band…”

Back in 2005, when Nick told me this, he added, “Steve Severin can verify this – he gave me a fridge two weeks ago!” Steve Severin was the bass player for Siouxsie & The Banshees. I am Facebook friends with Steve – even though we’ve never met or spoken and he has never offered me any white goods – so I messaged him and asked him if he could confirm.

Not. A fucking. Sausage.

Kevin booked the bands at the Batcave and Flesh For Lulu stood out. Things were coming to an end with Specimen for him – it was all getting a little bit too camp and cabaret. After Marsh died, Kevin wrote on Facebook that he joined Flesh For Lulu in 1984 “because I wanted to play in a band with Nick. Something about Flesh For Lulu made them stand out from the hundreds of bands on the London club circuit. That something was Nick.”

He had it all, said Kevin: “a great voice, a huge stage presence, a fistful of spiky, melodic tunes, he played a cool Fender Jazzmaster with a punk attitude – he was a killer guitarist with an instinctive grasp of soul music, rock & roll, r&b, Tamla, Atlantic, Stax, blues, country and punk – and of course he was a handsome bastard as well.”

Kevin Mills watched Flesh For Lulu play the Batcave and he thought: “This band are amazing. Well, all except the bass player.”

So soon Glen was out, Kevin was in and Rocco was worried.

“To be honest, I didn't want Kev in the band,” says Rocco. “That girl I mentioned, whose parents were doctors? The ones who got me off heroin? Kev was madly in love with her and she’d left him. Luckily for me – I may not have been alive if it wasn’t for her. What I didn’t know until later, is that she was Kevin’s girlfriend. So I thought, ‘The worst thing that can happen, is that Kevin’s going to join my band – that’s going to make it really sticky.’”

And Kevin Mills wasn’t just joining the band – he was taking over. Kevin was driven and he was a fan, a Flesh For Lulu convert, who thought they could be huge and set about making it happen. “The first thing I did,” says Kevin, “was go, ‘Who’s this guy that’s managing you? He’s useless, can you not get rid of him?’ And that was Pete Webber, who’s still a really good friend of mine – I have no idea why, after that.”

Peter Webber had some experience of management as part of the Psychedelic Furs operation. Kevin waded right in: “Pete, man, why are you only paying these guys ten quid a week? Nobody can live on that.”

Kevin gave Flesh For Lulu a shake and Peter Webber fell out. “I think Nick and James went to Pete Webber and said, ‘Look Pete, it’s not really working out.’ I felt kind of guilty about that, but I also thought it was for the best. We were all quite driven in those days. I basically took charge of that band after he left.”

This meant that Kevin managed the band, tour managed the band, played in the band and helped write songs for the band for the majority of their career. All of them agree that this was a mistake.

“It nearly killed me,” says Kevin. “Honestly. I was a bit of a tyrant.”

This is how Rocco and James remember Flesh For Lulu’s management situation:

Rocco: Peter wasn’t sacked.

James: Yes, he was.

Rocco: I didn’t think Peter was sacked – I thought he left!

James: Kev kinda took over and that was disastrous.

Rocco: Who sacked Pete then?

James: I think we all did.

Rocco: Well, I didn’t – I didn't even know about it!

James: I think Nick did, because again, there was this thing about wanting to go to another level, and get a bigger manager. But then Kev doing it put a lot of strain on him because he was in two camps. If we’d had decent management, it could have had a different outcome. A manager could have said, “Cut the shit, forget about making a hit record, just do what you do.”

Rocco: Well, we had Ivor The Bastard, didn’t we?

James: But he wasn’t a proper manager.

Rocco: He was a tour manager, wasn’t he? But when we were with Static [Records] he was sort of managing us, wasn’t he?

James: Ish.

Rocco: Well, he was staying up all night and taking speed with us…

James: The next step up was supposed to be Perry Watts-Russell. But then he got ill. We literally signed with him and then he went, “Oh, actually, I’m ill, I can’t do this.”

This was later, when they really were close to becoming big time, when they had songs on Hollywood movies and were hanging out with Matt Dillon and John Hughes.

Perry Watts-Russell was the brother of Ivo Watts-Russell, the 4AD guy. Perry was based in LA, and well-connected. He was exactly what they were looking for: a guy with some clout and a bit of vision. But within two months of signing with him, Watts-Russell came down with some sort of dreadful condition that laid him up. He was bed-ridden. Incapacitated. They had signed with a manager who was now literally incapable of managing.

They couldn't even get him on the phone. His people would answer and say, “He can’t talk at the moment – he’s in a really bad way.”

“And I was in this terrible position,” says Kevin, “because I’m like, well, shit, you know, I really feel for the guy but at the same time: who the fuck is looking after us?”

Nobody was taking care of business. Eventually, the contract was cancelled by mutual request and Kevin took over again.

Back in 1984, Glen was out, session man Phil Spalding finished the job and Kevin Mills’s face was on the cover of Flesh For Lulu’s self-titled debut album, despite not having played a note on it.

In Sounds, Chris Roberts gave it four and three quarters out of five and Jack Barron called Restless and Subterraneans “two of the most exciting singles I’ve heard this year”.

While the rest of goth pack were trying to sound icy cold and creepy, Flesh For Lulu were warm and sexy, with a Stonesy swagger and a sinister turn of phrase.

‘We’re gonna break both his legs,’ went Hyena. ‘We are the dogs/The ones that bite to scar forever,’ went Dog, Dog, Dog. They were part Brixton and part Brooklyn, Nick’s voice Elvis-in-Vegas rich, Lou Reed cool, Sinatra smooth, the music cooked on the same spoon as Alice Cooper, Bowie, Johnny Thunders and The Only Ones, reverb guitars shuddering in the background, with choruses that bit and scarred forever.

It’s easy to write a story like this and focus on all the negatives – ‘Where did it all go wrong?’ – but this is the period where it all went right.

“When it started to take off, it was heaven,” says James. “You’re in a band, doing what you want to do…”

They met crazy people. Like Dead Or Alive’s Pete Burns who once, down the Batcave, took off one of his stilettos and smacked Specimen guitarist Jon Klein on the head with it.

“And the heel of the stiletto,” said Nick, “was stuck in his forehead! Jon Klein’s standing there with a fucking shoe sticking out his head! And then he pulls it out and blood shoots up like a fucking oil-well…”

The first big American tour, they hired a car, just the four of them, and the crew went in the van. They played all these seedy places, stayed in whorehouses. In Texas, pockets stuffed with narcotics, they got pulled over by cops, fucking police dogs jumping up on them. But instead of nicking them, the Sheriff got a kick out of these English freaks and let them hold their guns and pose for pictures.

One time in Brussels they got into a mass brawl with a bunch of football hooligans, Kevin swinging one guy into a plate glass window, thinking, ‘Oh, fuck’ as he let him go and, the guy just bouncing off it BOINNNG!! coming back into the room, arms swinging.

In Holland in 1985 they played a whole set of country and Cajun covers, stuff they’d been listening to on the tour bus: Bobby Charles and Lost Highway by Hank Williams. The writer Kris Needs came on tour to write a feature and made the band all these tapes – hip-hop, gospel, country, you name it – and it seeped into the music. James still has those tapes.

Maybe one day someone will write a book about Flesh For Lulu and, if they do, this is where all the gold lies. The stuff about drinking moonshine in Norway, or hitting post-Franco Spain, where everyone was up for a party and completely off their faces, or Aberdeen as the oil money kicked in and it was like the Wild West (“There were men fighting women, women fighting men, bouncers fighting each other…”).

Then there’s the American strippers that, y'know, looked after Nick and James, and the time Sisters Of Mercy frontman and fencing-enthusiast Andrew Eldritch challenged Rocco to a very public duel outside in the university campus in Glasgow and Rocco totally whipped him.

“I went to one of the worst schools in London,” says Rocco, “but they had this scheme for under-privileged kids and, you know, the fat kid and Big Nose are the last ones to be picked for the football team, so…”

So he took up fencing and made it as far as the Junior Olympic squad.

Eldritch didn't know this and at Glasgow University threw down the gauntlet. Eldritch was in his full gear, Rocco in a pair of leather trousers, some stuff borrowed from the sports department and holding a walking stick: “I’d jumped off a flight of stairs, off my head, y’know,” he says. “I didn’t break my ankle but I couldn’t walk for two months.”

It didn’t hinder his fencing.

“I fucking thrashed him,” he says. “I killed him. He didn't have a chance.”

There are nice quiet moments too, like the time after a gig at the Ayr Pavilion in Scotland, when they went swimming in the sea at night. “Somebody went, ‘Hey do you want to all come back to our place? Let’s go for a swim first’,” says Kevin. “We were like, ‘Fuck off,’ but everybody just piled down to the water and went skinny dipping. And it was brilliant.

"We just couldn’t believe it – the water was warm. I remember James saying something like, ‘Yeah, it’s the Gulf Stream,’ like, ‘Why are you so surprised? It’s beautiful here. It’s always warm on the West Coast of Scotland.’”

“Between 84-86 is mostly a big blur to me,” Nick wrote later. “Riding the night bus from Brixton to the West End in white leather mini-skirts in Thatcher Era Britain. We lived it. The stories are in the songs.”

This was Flesh’s golden age and the songs came easily. Finally dropped by Polydor, they got a deal with a small label called Hybrid, an imprint of Statik records, a Glaswegian label that also released records by The Chameleons, The Sound and Men Without Hats.

Their first release was a 5-song EP called Blue Sisters Swing. Lead track Seven Hail Marys was written in Hamburg, where Rocco remembers Nick fucking around with an old Frank Zappa song, Jelly Roll Gum Drop, and feeling guilty about using the same melody.

The song's lyrics about sin and Catholic guilt – no sin goes unnoticed by God’s all-seeing eyes, that kind of thing – were made flesh by the sleeve, an old 18th or 19th century engraving of two nuns making out while someone spies on them from below. Rocco says he spotted it in a book his girlfriend had and Nick hand-coloured it.

“It was just a bit of fun,” shrugs Rocco.

Predictably, in America far-right Christian groups came to their gigs to protest.

“We were like, ‘Who are they protesting against?’” says James. “Oh, us.”

In fact, the picture on the sleeve is not some ancient engraving. It’s from 1952 – just 33 years earlier – and called ‘Le Reve Claustral’ by Clovis Trouille, a French artist whose earliest work pre-dated the Surrealists.

The title ‘Le Reve Claustral’ (sometimes translated as ‘Monastic Dreams’) probably comes from a work of the same name by a turn-of-the-century French poet called Germain Nouveau – a poem that also seems to be about forbidden desire in a convent.

So was this an innocent mix up or a cheeky blag? The poet Germaine Nouveau was a friend of Rimbaud and Verlaine, two poets that James was reading and inspired by (“I was into poetry,” James told me, explaining the lyrics of Death Shall Come. “Arthur Rimbaud and Verlaine and all that sort of stuff”) so it was certainly something they could have stumbled across.

Equally, it’s not hard to imagine Rocco tearing a black and white version out of a book and, separated from context, forgetting the picture’s origins, or getting them muddled in his head. The Flesh version has been re-coloured, after all, and this was way before Google made all this stuff easily researchable.

I don’t know which is the truth and I don’t really care. I just enjoyed stumbling around the internet like a goth-rock Columbo.

Other highlights on Blue Sisters Swing included I May Have Said You’re Beautiful But You Know I’m Just A Liar, which stomped like the Stooges despite Nick having written it on ecstasy at New York’s famous Danceteria club, while a pre-fame Madonna worked behind the bar “in full Batcave garb”.

Rocco chuckled darkly through the goth-girl-group-country-folk of Who’s In Danger? and James contributed Death Shall Come, possibly Flesh For Lulu’s only real goth song, a brilliantly morbid epic that sounds unlike anything else.

“If I was asked to invent the perfect rock’n’roll band, I’d probably model it pretty closely on Flesh For Lulu,” Jane Simon wrote in her review in Sounds.

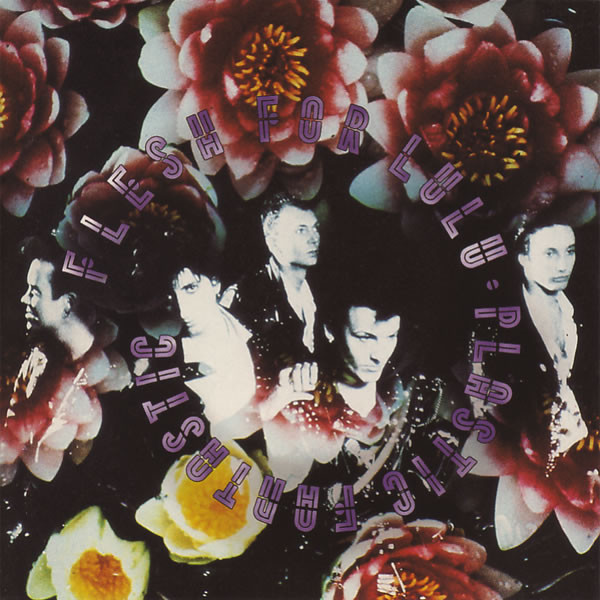

After Blue Sisters Swing came Big Fun City. Produced by Craig Leon, it was their greatest album. They choose Leon, said Nick, because “he was responsible for three of our all-time favourites, the Ramones first album, Parallel Lines from Blondie and Suicide”.

In turn, Leon chose Olympic Studios because of all the vintage equipment they had – gear that had recorded Led Zeppelin, Bowie, The Who and more. The band, said Nick, “were happy to see if the spirit of Sympathy For The Devil was still bouncing off the walls”.

It was. The Spirit of Sympathy For The Devil had been hanging around Olympic Studios, smoking fags out the back with The Ghost of Wild Thing and taking the piss out of the Phantom of A Night At The Opera. He was just waiting for a band like Flesh For Lulu to come along.

New boy Kev contributed the first single Baby Hurricane (“That might have been the first song I wrote for Flesh, actually”), a deliciously dumb rock song that’s probably about blow jobs but still sounds like a radio hit. Cat Burglar – originally the b-side to Restless – was remade and remodelled by a band at the top of their game and full of ambition: ‘Kick open that door 'cause I want more and I want it now’.

Rent Boy’s piano part vamped and stumbled like Mike Garson’s intro to Bowie’s Lady Grinning Soul, while a brass section swelled and Nick’s rich voice made being a male sex worker sound like a pretty solid career move: ‘Everything that you do/She’s gonna use you/Cindy’s got a job for you/And there’s bucks in it too’.

Golden Handshake Girl was Sweet Jane-Goes-Stax. Just One Second, a gorgeous Gram Parsons-style country song. Craig Leon got them to play the backing tracks live, giving the album a loose rock’n’roll feel that they would never recapture.

The Spirit of Sympathy For The Devil was pretty pleased with himself.

Outside of the spirit world, though, no-one gave too much of a shit. Big Fun City went unnoticed by the mainstream. In 1985, the indie music press had The Smiths and The Jesus And Mary Chain to get excited about. Flesh For Lulu were not heavy enough for Kerrang! and not goth enough for the audience they’d attracted through tours with Specimen and The Sisters Of Mercy.

“We didn't really know what we were doing,” says Rocco. “We only knew we wanted to be a rock’n’roll band and that we didn’t want to be pigeon-holed as a goth band.”

Their brilliant, open-hearted eclecticism was their undoing. “I think it harmed us,” says Rocco. “I wouldn't change it, but I think it made it difficult for record companies knowing how to market us. Rock’n’roll wasn't that successful then either. Hanoi Rocks did alright, but they were quite cartoonish. They were like the New York Dolls and they toured with Johnny Thunders. But a band like us, playing a country song and a weird goth thing…”

There was one plus: Beggars Banquet, the home of Bauhaus and The Cult, became their new label.

Struggling to connect in the UK, Flesh For Lulu looked elsewhere.

Not only were Flesh in love with the music of the USA, they were treated better over there. “You’d turn up at somewhere like Retford Porterhouse and go, ‘Where’s our rider?’” says Kevin. “‘Where are all the beers and stuff?’ and the bloke would go, ‘You’ve got four fucking cans of Kestrel lager. Take it or fucking leave it.’ There was just this endless,” he searches for the words, “…being treated like cunts, basically.

“Then we went to America and there’d be like two bottles of tequila, a crate of wine, a massive table heaving with buffet, all really nice food. You’d give them a rider and they’d actually give it to you! And the audiences were amazing. They’d go crazy, fucking mental, and we just went, ‘Let’s play here for the rest of our lives’.”

On their first tour of the US, they took turns driving. Rocco would drive in the morning so that he could drink at night. “The problem was getting me up,” he says. “So Kev used to put a big line of coke next to my bed, and tap me on the shoulder – ‘Up!’ – and I’d do the first stint.”

Who, I asked Kevin, was the main troublemaker in the band? “Rocco,” he said, without a second thought. “He might deny this, but – if you speak to him and he denies it – he’s lying. He knows full well.

“Unfortunately, Roc substituted the skag for booze and for the next few years he was consistently out of it, basically. In a lot of ways, Roc was the ultimate rocker…”

It got really tiresome after a while, he says, because Rocco was just permanently off the hook, and he tells me this story to illustrate: They were in the States, somewhere like Cleveland, staying in some posh hotel, and Rocco and Mark Edwards, one of the road crew, went to the bar.

“There was a bunch of guys in suits drinking. Rocco’s already completely out of it. He reels up to the bar, and mumbles, ‘Jack and Coke,’ and the guy behind the bar goes, ‘No, you’ve had enough, buddy,’ So Rocco went, ‘Give me a fucking Jack and Coke’.

“He’s pointing at these businessmen going, ‘They’ve got fucking drinks, why can’t I have a drink?’ So, the guy went, ‘I told you, I’m not serving you, get the fuck out.’”

But Rocco did not get the fuck out. Instead, "he got his cock out and just started pissing literally all over the bar, and all over these guys.” When the barman went for his baseball bat, Mark grabbed Rocco and the two of them ran.

“We all kind of held him in this sort of weird awe for doing things like that,” says Kevin, “because it was true rock’n’roll behaviour. I mean, none of us would do shit like that. But the reason Nick and Roc became such a team, was because Nick wasn’t like that and I think he always wanted to be. Nick wanted to be more like Rocco.

“He wanted to be more rock’n’roll and that became a bit of a problem as well, because he started drinking more, taking more drugs and trying to affect a more outrageous persona.”

“Nick and Rocco took it to another level,” says James, “so me and Kev became the sensible ones. I think Nick tried to keep up with Roc. And maybe he wasn't as strong as he was. Roc’s a real survivor. And Nick had more pressure on him. He had this insecurity…”

“I think Nick needed me cos I’m quite fearless,” says Rocco. “I don't give a fuck. Maybe because I come from such a rough background. I don’t think Nick wanted to be like me – I think he saw something in me that he wanted to possess. The way I saw it, I’d kick the door down and then, when we get in there, ‘Sort it out, Nick’. Cos Nick was always the boss, the way I saw it. He was always the Guv’nor.”

“To me, it’s not just about the music, it’s the whole lifestyle of it. Whatever people say about touring, apart from being onstage, it’s still incredibly boring. How bands go on tour sober, I don’t know. I don't know how the fuck they do that. I just couldn’t imagine it. Staring out of a window all day, reading your book, whatever.

“I did do a gig sober once, I hated it. Nick made me do it. I just couldn’t wait to get off.

“For me, there’s been some amazing artists and as soon as they stop drinking or doing drugs, they just turn crap. They just never write another good song. And if me and Nick were still doing it, we’d still be at it.”

The division between The Drinkers and The Sensible Ones affected the band’s writing.

By Blue Sisters Swing, they were all writing. They didn’t write together. Instead, individual members would bring in their songs almost fully finished. They would rehearse it and, if it worked out, the songwriting credit went to the whole band.

“Then after a little while it got a bit fractious,” says Kevin, “because James and I ended up writing the bulk of the songs, and Nick and Rocco had, sort of, laid back a bit.”

The Drinkers weren’t really contributing as much and Kev was really disappointed in that: “I really wanted Nick to write the bulk of the songs. I just thought he was a great song writer. I wanted to write but I didn’t want to become the dominant songwriter. I wanted Nick and James to carry on writing together. I was a big fan of their writing.”

Eventually, The Sensible Ones came to a sensible conclusion: that if they were going to do all the writing, they should get all the songwriting credits too.

“We really did it to give Nick a kick up the arse,” says Kevin. Nick and Rocco got really upset, like ‘We can’t do that, we’re a band’ and in the end they came to a compromise: the whole band got a credit, but the person that actually wrote the song also got their name on it.

And that’s the way they went into next album, Long Live The New Flesh, recorded at Abbey Road with Mike Hedges.

“There were a couple of sticky moments,” says Rocco. “I mean, that song, Way To Go. Just: what the fuck is that? It sounds like Simply Red. It’s awful.”

Long Live The New Flesh was recorded over three months with Mike Hedges at Abbey Road, Studio 2. The Beatles recorded Come Together in that room. Johnny Kidd & The Pirates did Shakin’ All Over there. Matt Munro sang From Russia With Love.

Somehow New Flesh still came out sounding like it was recorded in LA for American radio. Which was exactly the idea. New UK record label Beggars Banquet, says Kevin, “wanted a record that would sound big and they could shift in America. I mean, so did we. Mike [Hedges] had been told to deliver that sound.”

“We went in the studio with Mike Hedges,” Nick said, “and on the first day we started playing and getting the monitor mix together and me and Rocco were like, ‘Where’s the fucking guitars, man?’ and [Hedges] said, ‘Do you want guitars?’ We were like: ‘Oh fuck’…”

Whatever, Mike Hedges did what he was asked to do: New Flesh was their biggest-selling album and took them to a different level in the States. Today, the production sounds a little bit 80s – polished and over-produced – and the songs a little bit thin.

“I can’t stand it,” Nick said. “And an album’s a bit like tattoo. I’ve been carrying it around, this insipid, fucking…”

The songs were solid (Good For You, Lucky Day, Sooner Or Later) but there were only a few bonafide FFL classics. The Replacements woulda sold their Ma for Kevin’s contributions – Postcards From Paradise (later covered by Paul Westerberg and the Goo Goo Dolls) and the effortlessly cool Sleeping Dogs, while Nick’s Siamese Kiss stomped with a gleeful Glitter Band beat.

This time the band’s influences – always eclectic – threatened to totally undermine the Flesh For Lulu brand. “Around the time of Long Live the New Flesh, Nick had this really big thing about Prince,” says Kevin. “He loved Prince, he thought the guy was a genius – we all did – but we had to steer him away from the Prince element a little bit because we thought it was getting a bit away from the sound of the band…”

To an outsider, it felt like a cynicism had crept in. The edges had been filed off. Gone were the days of horny lesbian nuns and ‘I’m gonna break both his legs’. Instead, the artwork featured a corny air-brushed logo of a winged heart against a city skyline.

Songs like Crash were breezy and nice. Hammer Of Love nailed Peter Gunn horns and a funky bassline to a lyric about table-top shagging. And then there was Way To Go, which did sound a bit like Simply Red.

Way To Go was another one of Kevin’s. The stress of recording it – the search for perfection and the drive for success – signalled the beginning of the end for Rocco. “It’s a fantastic song,” he says, “but the way it was played… There was one line, I might have been a millisecond out and Kev made me play it and play it and play it. And finally I went, ‘You know what? You play it.’

"And that was the seed that went on to the next album. It got to the point that whatever I played, it just wasn’t good enough. And I thought, ‘You know what? I’m not in this band anymore.’”

There was a bigger picture. Kevin was reaching breaking point: writing songs, playing bass, managing the band. It was around this time that Perry Watts-Russell got involved. Kevin’s preferred choice for manager was a woman called Janet McQueeney, but Nick and Rocco wouldn’t go for it. Then the Watts-Russell thing ended in disaster.

“He got the hump about that,” says Rocco.

“It drove a wedge between us all,” agrees James.

Trust Hollywood to promise a happy ending. The movies of John Hughes – actually made and set around Chicago – were single-handedly changing the fortunes of British alternative rock bands, with soundtracks that were as smart and quirky as his characters.

Hughes was a music nut with an Anglophile’s knowledge of new wave and alternative rock. “I always preferred to hang out with the outcasts,” he said, “‘cos they were cooler. They had better taste in music, for one thing…”

Simple Minds got a US no.1 out of the soundtrack to 1985’s The Breakfast Club with (Don’t You) Forget About Me. The Psychedelic Furs had their biggest UK hit with the title track to Pretty In Pink, and the soundtrack album also included songs by New Order, Echo & The Bunnymen and OMD. Suddenly, British alternative music had something bigger to aim for than four cans of Kestrel at the Retford Porterhouse.

Peter Webber – the band’s former manager – was working with Psychedelic Furs and told Flesh For Lulu that Hughes was looking for a new song for his next movie Some Kind Of Wonderful. James bought himself a 4-track and knocked up I Go Crazy quite quickly.

“Nick tidied it up,” he says. “I had a big argument with him about it, actually. It was much darker. It really was ‘I go crazy’. It was a song about depression, about not being happy, punching a window over some girl I’d been seeing.”

Nick re-wrote some the lyrics, softened it up a bit for Hollywood, and they got Pet Shop Boys producer Stephen Hague in.

“He was a bit of a twat,” says James. “He had this girl who’d sit and roll him spliffs. He tried to get a songwriting credit because he changed a chord in the middle eight. He did a flat A instead of a major.” They had to take it to two musicologists to avoid giving him a percentage of the royalties.

It was their biggest hit – a cool Billy Idol-like pop song that was a great vehicle for Nick’s voice. In the video, the band are heavily styled and Nick is all exaggerated arm-movements. He’d decided he didn’t want to play guitar anymore. He wanted to be a frontman. He had a new persona he wanted to try out: Nick Nasty.

“He just wanted to be Iggy Pop or something,” says Kevin. “I think that ‘Nick Nasty’ was his idea. But then Ivor Wilkins, our tour manager, started calling him ‘the harsh Marsh’ – Nick Nasty, the harsh Marsh. Nick used to get slightly peeved because he always thought we were taking the piss a little bit.”

They had brought in a fifth member during the recording of New Flesh: Derek Greening (aka Del Strangefish), formerly of Peter & The Test Tube Babies.

Derek remembers first meeting them at a show in Germany where Flesh For Lulu were supporting the Test Tube Babies. “There was a riot outside between punks and skinheads,’ he says. “Rocco and Nick were in the dressing room going, ‘Are we gonna be alright?’”

Derek was a fan of Big Fun City and when he moved from Brighton to Brixton he “used to drink down the Prince Albert on Coldharbour Lane, which was a hangout for punks and goths and stuff. We became mates and they asked me if I’d do a bit of guitar. Nick wanted to stop playing guitar on stage so that he could be free to move around more, be a bit more Iggy Pop.

“So that’s how it started – I didn’t realise I'd still be doing it eight years later.”

Maybe one day someone will make a movie about Flesh For Lulu and, if they do, this will be the bit they go to town on. The band’s gritty beginnings in Brixton and the Batcave will be squashed into the first 20 minutes and the rest will play out like a goth-rock Entourage – set in the American sunshine, with the band in shades and black leather jackets, surrounded by beautiful women, Hollywood directors and flash cars.

“My favourite memory,” says Derek, “is a tour we did with The March Violets on the back of Some Kind of Wonderful. Paramount Pictures backed the tour. I’d toured America before in the back of a Transit van with 24 other guys with hairy arses, so this was something else. Paramount was picking up the tab, so we’d get driven everywhere in Limousines, stay in 5-star hotels, and everything was free.

"Back home in Brixton we’d have padlocks on our fridges. Here, there was free champagne, free Jack Daniel’s, free everything.”

At the end of the tour, they played at the Palace in LA. It was, wrote the LA Times, a big night “for scores of just-about-to-be-somebodies”. Some Kind Of Wonderful premiered earlier that night at the Chinese Theater and the audience at the Palace included John Hughes, Eric Stoltz, Lea Thompson, Mary Stuart Masterson, Andrew McCarthy, Molly Ringwald, the Bangles, Andy Summers, Michael Des Barres, the Beastie Boys and Rutger Hauer.

They had signed to Capitol. They were playing bigger venues. John Hughes had signed them to his publishing company. Aerosmith’s Joe Perry said that Long Live The New Flesh was his album of the year. They got the big tour bus, they played the bigger venues, they stayed at the big hotels… It was the rock’n’roll dream come true. Success, glamour, on the cusp of the big time. But something still wasn’t right.

“John Hughes used to take us out,” remembers James, “and he’d say, ‘Here’s my number – if you need anything, just call me’. And you’d ring it and it’d be dead. A dead number.”

“The last album,” says Rocco, “was just a nightmare.” They settled on this guy Mark Optiz, an Aussie who’d produced Australian bands like Cold Chisel and Jimmy Barnes. Optiz was part owner of INXS’s Rhino Studios in Sydney and suggested they do it there. Beggars Banquet, hoping that a little bit of INXS’s magic would rub off on them, said yes.

The band arrived in Australia exhausted and sick of the sight of each other. There was a lot of drinking and a lot of downers. By his own account, Kev was driving everyone mad, himself included. “I probably had a few breakdowns and didn’t even notice,” he says. “Just came out the other end and started again.

“I was a control freak. I was really trying to control the destiny of the band, not for my own ends, but to get us where I thought we should be. It’s not a good idea to be a manager and be in the band. You lose the dressing room, as they say. And I really did. The more you think you’re doing it for everybody’s benefit, the more they resent you for it.”

Around that time, James discovered that a childhood accident – where he’d crashed his bike and impaled himself on the handlebars (“I very nearly died, it ripped my bowels open. I had a blood transfusion, septicaemia, everything”) – had left him with a permanent back problem.

“I went for an X-ray and they were like, ‘Oh, you’ve broken your back, actually’. I had no idea.” To counter it, the doctors told him, he had to stay fit. He’d have to give up the life of excess he’d been living for the past few years.

In Australia, he started going to the gym. Nick didn’t approve. “Nick couldn't handle the fact that I went swimming or went to the gym,” says James. “He thought it was really unrock’n’roll. I said, ‘Nick: I have to. I can't physically play if I don’t’.”

The songs weren’t there. James hadn’t written much, Kev didn't want to and Nick was trying to do his funky Prince kind of thing. Derek stepped in. “His songs were a sort of poppy,” says Kevin. “I suppose, more commercial, but I didn’t really think they had the intensity of the earlier Flesh For Lulu songs.”

To add insult to injury, it turned out that the deal Derek had signed meant that, where the original four split the royalties on each song, Derek kept all his royalties to himself. “Someone should have stood up to him,” says James, “but by that point…”

Nick later told Vive Le Rock magazine that "Del wrote Time And Space, which is without doubt the most stupid, saccharine piece of shit pop song, without any redeeming features. Of course the record company fucking loved it and stuck it straight out as a single.”

Which was a bit naughty of him, really, and might just illustrate Kevin’s points about Nick's failure to step up at times. Nick was the singer, frontman and founder of Flesh For Lulu. If he didn’t like that song, and if he didn't want it as a single, maybe he could have shown some leadership – refused to record it, halt its release. It just wasn’t his way.

“Nick was quite a humble or non-confrontational guy,” says Kevin. “He wanted what he wanted but he didn’t want to have to bully people or to have to drive at it in order to get it.”

For Rocco it came to a head during the recording of the album opener, a song by Kevin called Decline And Fall. “There’s a lot of guitars on that,” says Rocco, “and they’re really quite intricate and I’m not the greatest guitar player. What I’m good at is just doing weird shit, making them sound different, you know? I spent two days with the engineer Al, 12 hours a day – I mean, we were doing coke and whatever, having a great time – and at the end of it Kev walked in.

"He didn’t even listen – this is why I knew it was bullshit – he walked in and after about four bars, walked back out again and went, ‘This is rubbish. Get Nick to play it.’ And I thought, ‘I’m not even going to bother playing guitar’. I just went off and got drunk in the bars in Sydney. I walked out of that record, literally half way through it.”

Nick, meanwhile, was having at go at James over his drumming. “I knew my limitations as a drummer,” says James. “I had the energy but I was never going to be Topper Headon. And that’s what Nick wanted, or thought he did. We all started to slag each other off. Kev would say to Nick, ‘You’re out of your head. It’s hard to get a vocal out of you, you’re just slurring’, too much coke or whatever.

“Rocco was too pissed. Kev was imploding. Derek was in the band, and really all the best stuff was written when it was just the four of us. We were top of college radio in America and playing quite good venues and then we went to Sydney and it all blew up in our faces.

“We lost sight of what we all did. We became too success-hungry. We were all trying desperately to break through to next level and we lost sight of what made us good.”

The finished album, Plastic Fantastic, was pretty well represented by its two first singles, Decline And Fall and Time And Space: two completely average, characterless, and instantly forgettable rock songs.

“The songs were less sexy, less sensual, and they lacked some of the charm that those early songs had,” says Kevin. “It seemed to be devolving back into this sort of – I don’t even want to say it – pub rock kind of thing, where you’ve got these rocking songs, but there’s nothing mysterious or alluring about them. It’s just straight ahead boogie.”

The best songs were Nick’s. Stupid In The Street sounded like like New Sensations-era Lou Reed – warm and doo-woppy – while the title track closed the album with a slow funk that might have been the closest he got to nailing the Prince vibe he was looking for.

'I'm a sci-fi baby of the twenty-first century,” he sang at the end. 'That’s me/Plastic fantastic/I can feel it when you talk/See it when you walk that way… Bye-bye.'

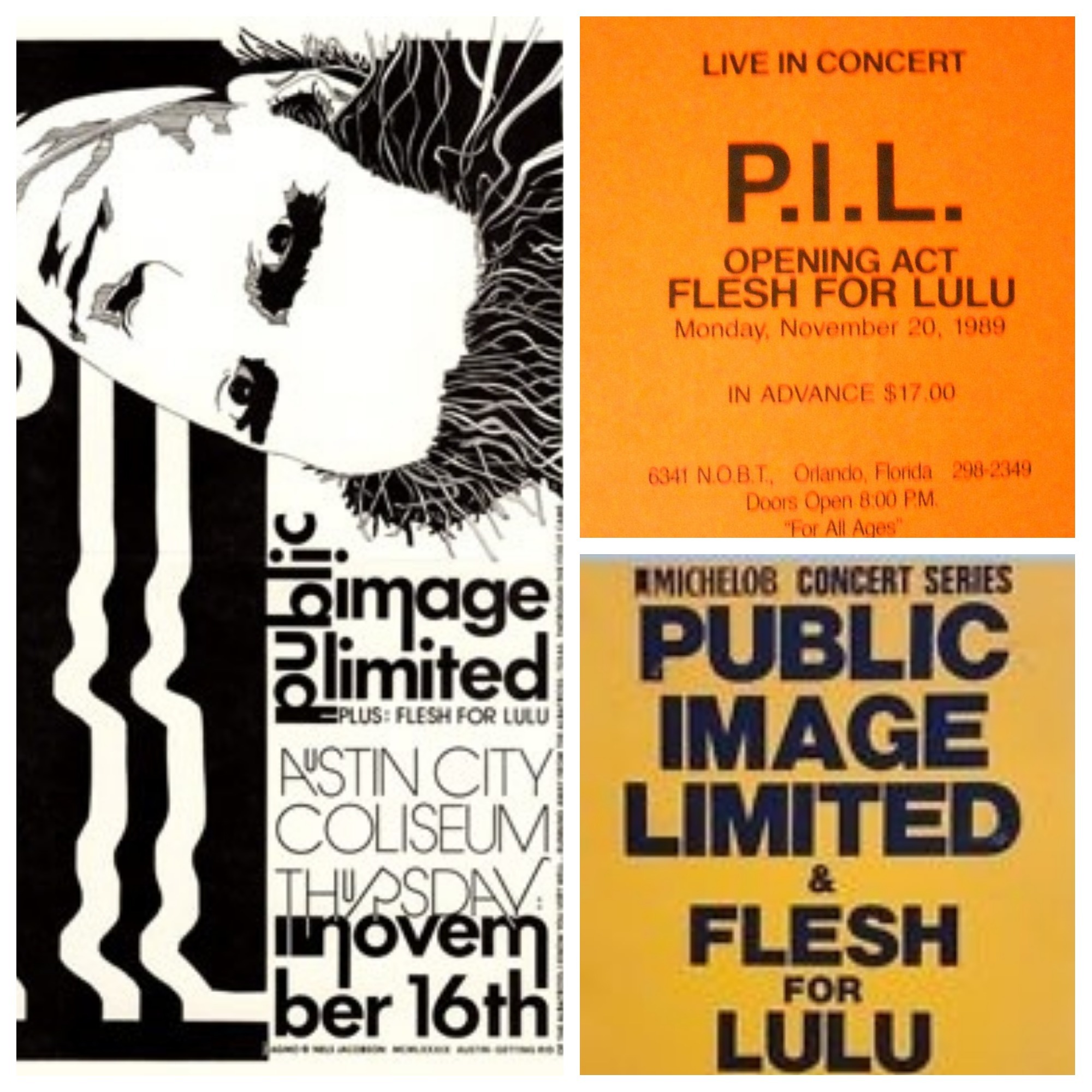

But the story wasn’t quite over. Kev had landed them a massive tour supporting Public Image across the States and Canada.

“I worked my balls off getting this tour together,” says Kevin, “and just as we were about to go out on tour I got a call from Nick.

“Nick went, ‘Yeah Kev, I don’t want to work with you anymore. Or James.’ I was like, ‘Are you kidding?’”

Alright, Kev could sort of see it coming, but still. So they talked for a bit and Kev accepted it was over. “I said, ‘OK, but after the tour, yeah? Let’s go out on a high.’”

But Nick was adamant. He didn’t want to go on tour with Kevin or James. And, Nick said, Rocco felt the same. Their minds were made up.

So Kevin and James were out on the eve of the biggest tour the band had ever done. “I was like, ‘Well, fuck you very much,’” says Kevin.

Rocco doesn’t remember it this way. “I don’t think anyone was sacked,” he says, even when I tell him that Kevin says Nick called him up and fired him over the phone.

“Nah,” says Rocco.

“Yeah,” says James. “He did.”

Rocco: “Did he?”

“Yeah,” says James.

But Rocco still doesn’t think anyone was sacked. Not really. The way he remembers it, they got back from Australia – Rocco, Nick and Del flew to Bangkok for Christmas Eve 1988, went mental, flew back home – and when they’d been back for a bit, Rocco phoned Nick and told him he was leaving.

He’d come back and had a good chat with his partner at the time – Cleo Murray, the lead singer of the March Violets – and between them they’d agreed it was time to move on.

When he told him, Nick was shocked, but after a while he rang back and said, “I’m leaving as well. We’ll leave together.”

(The year before he died, Nick told Vive Le Rock this exact story, but the other way around: “We came back to London and I said, ‘I quit’ and Rocco said, ‘I quit as well then’.”)

Rocco and Nick called a meeting in a pub in the West End at 11 in the morning. “I was in at half past 10,” says Rocco, “fucking drinking a whisky before they got there. I was dreading it.” Things had snowballed: suddenly the two of them were carrying on and James and Kevin were out. Rocco tried to keep his head down. “I was like, ‘You know what? Whatever’. We all met. It didn’t even last that long…”

“I was basically sacked from my band,” says James. “The band that I started.”

So it didn’t end particularly amicably. There was a cease and desist order and some legal squabbles. After a while, Kev heard that they’d got new management, a couple of fucking guys, Pushy and Cushy or some shit – Mr. Pushkin and Mr. Cushberger – two American dudes who were like, “Hey, we’re a shit hot management team!” But it was a disaster and after the Public Image tour it all fell to bits.

Both Kevin and James couldn’t help but take a little bit of satisfaction from that.

On one hand, Rocco describes the PiL tour as a bit of a laugh – big venues, great hotels – but the stories from the tour are dark. Nick told Vive Le Rock that one night John Lydon spiked his drink with peyote, and then whispered in his ear all night, tormenting him and turning Nick’s trip bad. There’s another story involving a serious unprovoked assault that I only have anecdotal evidence of.

And then there was the Lydon brawl.

They’re on the PiL tour and Rocco hits it off with PiL guitarist John McGeogh: “a lovely guy. Scottish, always pissed. I used to call him The Chardonnay Kid,” says Rocco. “He’d call your room. [Mimics McGeogh on the phone, in thick Glaswegian] ‘Hey! Ah’m in tha jacuzzi, man! Wi’ a bottle o’ Chardonnaaaay!’ I mean, literally: 9 o’clock in the morning, most mornings, it’s McGeogh, ringing you.”

One particular day, Cleo flew in and that night everyone ended up at a club, sat at the bar. Rocco’s got Lydon on his right and Cleo to his left. Nick’s the other side of Lydon. The house band are playing Flesh For Lulu songs and they ask Rocco to come up and play guitar with them. Afterwards, when he sits down, it feels like Lydon’s a bit weird about it.

Lydon had been bragging about how much he’d spent on this shell suit he was wearing. “He’d bought it in a Hilton over there and it’d cost him 400 bucks,” says Rocco, “for this nylon Adidas thing. Meanwhile, Cleo had bought me this Indian shirt for, like, 130 quid from Kensington market. That was a lot of money in those days.

“Lydon gets this big black marker and goes – bleueurgh! – draws a big black line down my lovely, light blue Indian silk shirt. Like, nice. Well done, mate.

“So I thought, fuck you.”

Rocco was a chainsmoker at the time. He looked Lydon in the eyes, turned the lit end of his Marlboro towards him and – Pop! Pop! Pop! Pop! Pop! Pop! Pop! Pop! – jabbed it all over his new tracksuit. “I totally ruined it,” he says. “So he takes a swing at me.”

Except Rocco ducks and Lydon hits Cleo, knocking her clean off her chair. Rocco swings at Lydon, and hits him in the neck, knocking him to the floor. “I mean, I can’t fight,” says Rocco, “look at me, but before I can even get down there – I was gonna help him up, to be honest with you – some bloke grabbed me from behind…”

They’re both kicked out of the club and the fight continues out in the street. Lydon had a bodyguard, a big American fucker, but of all the nights, he wasn't there. All Rocco remembers is the two of them ending up in the gutter, Rocco on top, trying to stop Lydon from going mental, basically, and Lydon saying, “Don’t hurt me, I’m your friend!”

The next morning, the phone rings and for once it’s not The Chardonnay Kid, it’s the band, having a right go: “What the fuck are you doing, hitting John Lydon? We’re off the fucking tour!” all that.

Fuck that, says Rocco. We’re only on it because they haven’t sold enough tickets.

They go down to soundcheck. Lydon used to do a soundcheck every day, but on this day he’s not there. They walk in and suddenly PiL stop playing and start cheering and clapping. McGeogh is like: “Fucking well done, it’s about fucking time someone did that.”

It was fine – they were still on the tour.

Lydon didn’t do any soundchecks for the rest of the tour. He kept himself to himself, and at the last show in LA, made his move.

“There was a backstage bit,” says Rocco, “but there was also a backstage of the backstage with a rope across it, so you could go back after a gig and have a line or whatever. So I was back there, doing one, and I turn around and it was him.

“And he went, ‘You do forgive me, don't you?’ I went, ‘Fuck’s sake – of course I do!’ I think he waited because he couldn’t face Cleo. I think he was pretty embarrassed.”

Plastic Fantastic flopped. It came out in the UK four months after the US release, in 1990: the year of Pills 'N Thrills And Bellyaches by the Happy Mondays, Jane’s Addiction’s Ritual De Lo Habitual and Fear Of A Black Planet by Public Enemy.

Plastic Fantastic seemed to belong in a different era. It had cost £400,000 to make. “Put it this way,” says Kevin, “it’s probably part of the reason why we haven’t seen any solid royalties for any of our stuff…”

Derek returned to Peter & The Test Tube Babies’ and later that year, Rocco and Nick popped up on their album of Stock, Aitken & Waterman covers, The Shit Factory, and then faded from view, officially announcing a split sometime in 1992.

“It’s hard to remember,” said Nick, “because the 80s is really trendy now, but at the time if you were a band that was around in the 80s, you were shit on the shoe of fashion and the music industry. We were so fucking unhip all of a sudden. Everyone hated an 80s band.”

Grunge changed the musical landscape yet again. By the mid-90s, alternative rock was big business and Nick and Rocco rallied once again. They dropped the name Flesh For Lulu and put together a band called Gigantic.

“This is where me and Nick fell out a little bit,” says Rocco. “Once Nirvana came along, Nick felt that bands like Flesh For Lulu were redundant. And in the short term we probably were, because those bands – Smashing Pumpkins, Nirvana, Hole, all those – changed everything. So we went through this whole period writing songs, and we knew we could make a really good record, and we’d make it heavier and guitar-y… But Nick wanted to change the name. I was like, ‘Noooo…’”

“We’d done a record that sounded current and we wanted a new start,” said Nick. “It was kind of stupid and insecure. We thought, ‘Let’s get a new bass player and drummer and start again!’ It was a stupid idea, really, because people knew us as Flesh For Lulu. But we changed our name to Gigantic and got signed to Columbia, went to LA with Tim Palmer and did this album and it fucking kicks arse. But we got dropped before it even came out.”

They signed a big record deal with Columbia, played football stadiums with Bush, at the height of their fame, when singer Gavin Rossdale was going out with Gwen Stefani and the papers were all over them. It looked like they were finally on the road to becoming a stadium band. The album got sent out to the press, got good reviews – and then never came out.

The A&R guy who’d signed them, Nick Terzo, had also signed Alice In Chains and the way Nick Marsh remembered it, “the singer in Alice In Chains was shooting a lot of dope and there was trouble between the A&R guy and the head of the label.”

Terzo left and the head of the label said, “Fuck you – and fuck those Limey guys as well…”

Later, says Nick, “We got signed again as Gigantic to Music For Nations and they fucking dropped us before it came out again. So me and Rocco went, ‘Fuck it’.”

The album couldn’t have been more perfectly titled: Disenchanted. Nick and Rocco formed and joined a dozen little bands in the following years before giving up on the dream.

“After getting signed and dropped, signed and dropped, I thought, that’s it, I’ve had my innings,” said Nick. “So me and Rocco went our separate ways for a while.”

After Flesh For Lulu, James Mitchell formed a band where he sung and played guitar. Former Flesh For Lulu manager Peter Webber did a video for one of their songs, but ultimately it didn't happen. James did a course in screenwriting and is now writing his second novel.

Peter Webber became a well-known director, working in film and TV and most famous for his 2003 movie debut, Girl With A Pearl Earring, starring Scarlett Johansson and Colin Firth, which won both Oscars and BAFTAs.

Kevin Mills had a couple of bands right after Flesh for Lulu where he sang and played guitar, and stayed in music for another 12-15 years, composing for film and TV. Today he runs his own Pet Taxi business – taxis that allow you to travel with your pet.

Derek Greening still plays with Peter & The Test Tube Babies and has his own radio show and podcast, Del Strangefish’s Punk Rock Show, on Radio Reverb.

Rocco Barker modelled for Dunhill with Christopher Lee and became the face of a supermarket in Germany. He starred in a reality TV series on Channel 4 called A Place In Spain – Costa Chaos, about him and his then-partner buying a property in Spain. In the Flesh For Lulu years he’d been a compulsive collector of vintage sunglasses. Now he has his own business, turning vintage frames into designer glasses. He also married, and has kids with, one of Nick’s long-term girlfriends – a woman, he says, who once hated him. “The last person I thought I’d end up with…”

The Spirit of Sympathy For The Devil climbed back into bed and pulled a quilt over his head. They were turning Olympic Studios into a cinema and he wasn’t surprised in the slightest.

Nick kept writing songs – not with a rock band in mind; something more intimate – and joined The Urban Voodoo Machine in 2003, filling-in for a gig and staying because he loved it so much. Raucous live shows, great songwriting, a strict dress code – Nick felt right at home. “I’m really only interested in having a good time,” he told me. “For everybody who’s in the band, it’s a party. I predict a lot of touring and shenanigans with this band.”

But he kept his own thing going too. In 2006, he released a solo album A Universe Between Us, a grandly introspective album with shades of John Barry and Scott Walker that really deserved even a fraction of the attention given to similar work at the time by Richard Hawley.

It was produced by Katherine Blake – formerly of Miranda Sex Garden and a founding member and Musical Director of the Mediaeval Baebes – and the two became a couple. Nick co-wrote songs for Katherine’s solo album, Midnight Flower, and she appeared on the cover pregnant with the first of their two children. (In October 2015, just months after Nick’s death, they released an album together under the band name From The Deep – a varied album of sultry folk and brooding country featuring both of their haunting, gorgeous voices.)

In 2007, Gigantic’s Disenchanted album was released as a Flesh For Lulu album called Gigantic. In 2009, a new Flesh For Lulu – with Keith McAndrew on bass and Mark Bishop on drums – released a ‘best-of’, with all of the songs re-recorded.

“It’s a bit of a middle-finger up to the record industry,” said Nick. “By re-recording the songs, we don't have to pay the labels. Plus, 20 years later, I’m a better singer, a better guitar player, and also the words carry this extra gravitas. You look back and realise what motivated you to write the lyrics, like, ‘Wow, I was some fucked-up kid’, y'know?”

His voice really had gotten better over the years. “Best I ever heard Nick sing was on the Gigantic album,” says Rocco. “Nick used to do this thing, right, where he could split his vocal chords. They wouldn’t be in tune but it was like two people singing, it was bizarre.”

The ‘best of’ album had one new song on it, which was also released as a single: Cold Flame, a song Rocco wrote back in the 80s (“with Nick’s help, of course”). Powered by a riff that’s a kissin’-cousin to the one on Thin Lizzy’s Rosalie, it is classic Flesh For Lulu. Cool, sexy and timeless, it could easily have appeared on any of their first three albums. ‘We’re snatching defeat from the jaws of victory,’ drawled Nick. ‘I’m gonna catch a falling star and set it free/ Just like a setting sun that glows until the end/Oh, we were lovers but we never could be friends’. It was the band’s last release.

Rocco gave up in 2013 and guitarist Will Crewdson replaced him. Crewdson had been a Flesh fan and later he was in the band Rachel Stamp and Gigantic supported them. “I couldn't believe that they were supporting us,” he says. “It didn't seem right at all.”

A friend of Will’s put them in touch with the Goo Goo Dolls and Flesh For Lulu joined their UK tour and played to packed audiences every night, including a night at Hammersmith Apollo.

And they recorded some songs too, says Will. A song called Crazy Eyes – “a very glam, T-Rexy type thing” – and another called Rock’N’Roll Won’t Get You Nowhere that was “almost like a doo-wop punk song. It starts off like something from Grease and then goes into full-on Flesh For Lulu, guitars wailing”. And they re-recorded Dogs, Dogs, Dogs. “As far as I know that was the last thing Nick recorded,” says Will.

Things thawed between James and Kevin and Nick and Rocco. They’d bump into each other around town and occasionally there was talk of getting the original Flesh back together, but it never really suited everybody.

But Nick never quit. One time James posted a link to the John Peel demos on his Facebook page and Nick called him, pissed off: “How dare you do that, James?” he said. “I’m trying to be Mr Rock’n’Roll now! This is destroying my image – I’m trying to get Flesh For Lulu going again!” They had a little spat about it and Nick rang back the next day and said, “I’m so sorry, I don't know what’s got into me. I’m going through a hard time. I was talking out my arse, it’s cool.”

“One of the things I love about him,” says Kevin, “is that he just kept going. That’s what he was born to do. He was born to sing and play, write songs and front a band – and he was great at it.”

In 2014, Nick was diagnosed with mouth and throat cancer. “I had a funny sort of blip in the corner of my mouth,” he said. “Like a grain of rice.” The doctors said it was nothing but he went back and insisted they take another look. “I just knew something was wrong. Gut instinct, you know?” He started writing about his treatments and battle against cancer on his Facebook page. “I didn’t know how else to approach it really,” he said. “I just thought, ‘Here I am’. Facebook is like an open diary if you want it to be.”

So his Facebook friends watched as he "had all my back-teeth on the right hand side removed in order to remove cancerous tissue from my mouth and a section of my forearm – including veins, tendons and skin – transplanted in its stead.

"The cancer had begun to spread into the lymph-nodes under my jaw, so a massive section of my neck was also dissected and removed. After surgery, I had a six week, intensive course of radiotherapy five days a week accompanied by six courses of chemotherapy. The sixth dose was withheld as there was a strong chance I wouldn't survive it, due to weight-loss and dehydration…”

The NHS oncology teams took special care not to zap his vocal-chords, he said. That throat of his – that golden larynx, the source of his to-die-for voice – was now the thing that was killing him.

In 2015, tests revealed that the cancer was still there and the fight started again. A Flesh For Lulu gig at the Brooklyn Bowl, inside London’s 02 Arena, was scheduled for May but brought forward to March.

Backstage, Nick showed us how wide, post-surgery, he could open his mouth (he would have struggled to eat a plum) but it didn’t affect his performance. The gig was a triumph: you couldn’t believe anything other than Nick Marsh was going to beat death.

“We finished with Sleeping Dogs,” says Will Crewdson. “It ends with the line ‘I’m gonna live til the day I die’ and he sung it twice – he’d never done that before.”

"Everyone was like, ‘He’s gonna beat it’ and I knew he wasn’t,” says Rocco. “At the end it was fucking horrible. Fucking awful. I don’t want to go into it.” He tells me about how once, returning home after a hospital visit, his body started to seize as he came out of the tube. By the time he got to his home in Westbourne Park, he couldn't move. “I think it was just shock. I think I went into shock. It was horrible.”

The cancer moved from Nick’s jaw and into his brain. In the last week of his life, friends and family – and fans – turned up at the hospice to say goodbye. He died on 5 June, 2015.

“I still find it really difficult,” says James. “I was angry when he died.” He found himself wandering around his house muttering, ‘fucking Nick’ under his breath. He thought they’d have time to fix things, maybe play together again. Just recently he’d started playing drums again and would definitely have played with Nick, if he’d been up for it.

“I feel embarrassed and regretful that we ended up having a go at each other over our musical capabilities,” he says. “Nick was the only good musician in the band. We weren't good to each other and I find that embarrassing. I wish that hadn't happened.

“And I’m embarrassed about our thirst to be successful,” he says. “It’s stupid – you should just do what you do. I regret that stuff. And I regret Nick not being here.”

“I spent more time with Nick than anybody else on this planet,” says Rocco. “We were inseparable. For years, if you saw Nick, you saw me. If you saw me, you saw Nick. We even lived together – and if we didn't live together, we lived like a street away from each other. It was only the last eight years of his life that I didn’t see him as much.

“I miss him. I miss my mate. I miss him so much. There’s a period where I just couldn't wake up in the morning without thinking about him.”

One day recently, he was alone in his workshop and he decided to put on Big Fun City. Halfway through Baby Hurricane, he switched it off. “I just couldn't listen to it,” he says. “It’s still difficult to come to terms with. I just feel like he’s just gone before his time.”

He gets upset and I apologise for bringing it all up again. “No,” he says, “it’s actually good to talk about it.

“It’s good to be able to talk about it. But it’s fucking hard to accept.”

Ironically, the last time the band were all together was at another funeral in Epping Forest in 2010. Lucy Wisdom had been a friend of the band and ex-girlfriend of both Kevin and Rocco – the woman who saved his life back when he joined Flesh For Lulu and came off heroin.

At Nick’s funeral, the sun shone, jets screamed across the sky and his friends saw him off in style.

The dress code said ‘Dress fabulous’ and they did. It was a thing about Nick. He always looked cool-as-fuck, dressed in vintage suits, great shoes, his hair perfectly sculpted.

“I dunno how you can wear those,” he said to me once.

Wear what?

“Jeans,” he said. “I dunno how anyone can wear jeans.”

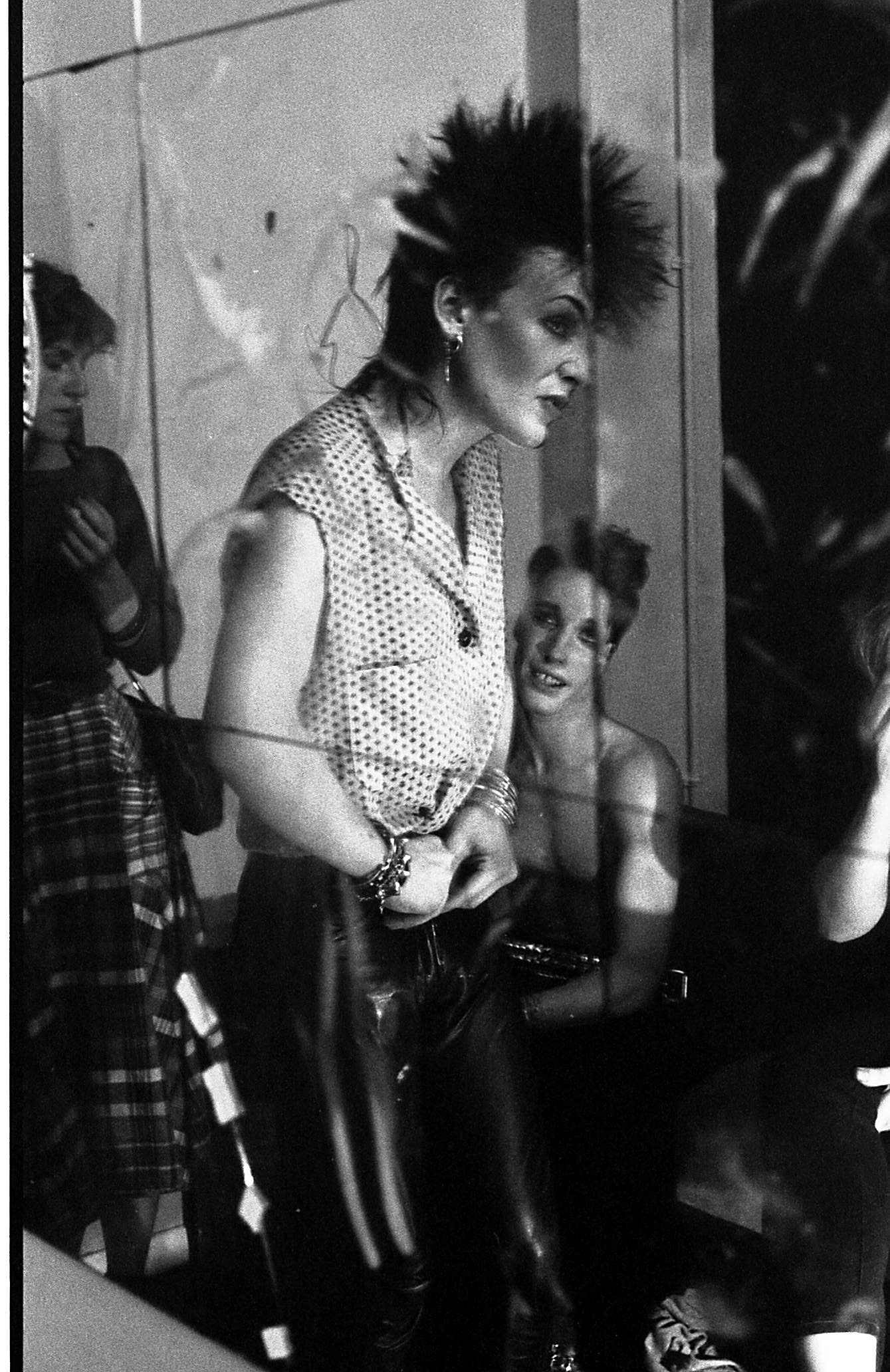

Many of the pictures in this feature were taken from Flesh For Lulu 1983 -1985, a photobook by Mick Mercer available from Lulu. A 'lost' Flesh For Lulu album, Cosmic Mind Fuck, was released last year and available from Bandcamp.