FORT BELVOIR, Va. _ A hearing to determine the status of a freed al-Qaida war criminal stalled Wednesday over a question of which Pentagon-paid defense lawyers can defend the Sudanese man who emerged as an al-Qaida affiliate spiritual leader several years after his release from Guantanamo.

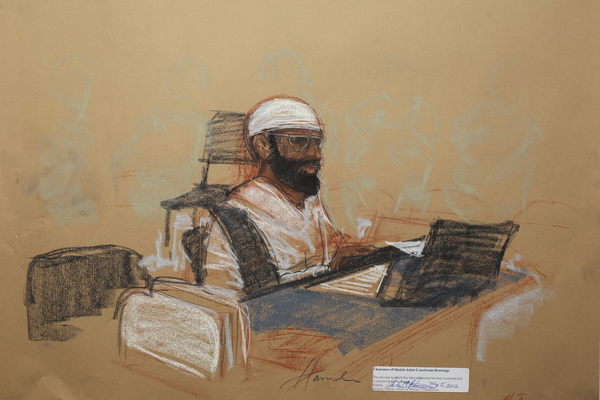

Army Col. James L. Pohl, the chief of the war court judiciary, called the first military commission session outside Camp Justice at the U.S. Navy base in Cuba to tackle a narrow question posed by a Pentagon appeals court: Is Ibrahim al-Qosi, 57, an unprivileged enemy belligerent?

The U.S. Court of Military Commission Review, or CMCR, wants an answer before it decides whether to overturn his 2010 Guantanamo guilty plea to providing material support for terror as an al-Qaida foot soldier.

But with the al-Qaida convict half a world away, perhaps in Yemen having left his homeland of Sudan, the first post-9/11 military commission hearing on U.S. soil focused on who can represent him. New attorneys assigned by the Marine general who runs the war court defense organization? Or his original, then-Navy lawyer who argues she has a conflict of interest?

Prosecutors said they had four unnamed witnesses to provide Pohl with facts, presumably about the whereabouts and activities of the man who emerged on a 2015 video preaching jihad against America as a leader of the Yemen-based al-Qaida of the Arabian Peninsula, AQAP.

But first prosecutors asked the judge to order lawyer Suzanne Lachelier, who as a Navy commander represented al-Qosi at his Guantanamo guilty plea, to represent him in the current fact-finding hearing. Lachelier, now a civilian, is an attorney of record on his appeal and also defends an alleged 9/11 plotter in the death penalty case. She told Pohl, who is also presiding in the Sept. 11 conspiracy trial, she has a conflict and cannot represent al-Qosi on the status question.

She notified the judge of the conflict in a court filing.

Instead, three other Pentagon attorneys are assigned to represent al-Qosi. One of them, Navy Capt. Brent Filbert, said in court that the trio had neither met nor had any contact with the man whose association with Osama bin Laden dates to the 1990s when al-Qosi was a bookkeeper in Khartoum.

Pohl agreed that, in court-martial practice, defense lawyers get to appeal a soldier's conviction without their explicit consent, or if the convicted trooper can't be located. But the Pentagon appeals panel, the CMCR, tasked Pohl with holding a fact-finding hearing on al-Qosi's at-large status in an order that Pohl read as suggesting Lachelier should represent al-Qosi _ but for her notification to the court of a conflict.

So Pohl stopped the hearing before it ever started to ask the review panel what to do. War court rules mirror military court-martial practice in some instances. But they also draw from federal, civilian court law, creating a conundrum not for the first time about the way forward at the war court President George W. Bush created in the aftermath of the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks.

"The reality of this dilemma is that we're in new territory. This has never been done," said attorney Michael Schwartz, also representing al-Qosi at the status hearing. He argued that, despite al-Qosi's absence and not knowing his lawyers, the man is entitled have his conviction of "crimes that aren't crimes" overturned. A civilian court ruled after al-Qosi pleaded guilt that, while providing material support for terrorism is a federal crime, it is not a Law of War violation and therefore can't be charged at a military commission.

The hearing drew a standing-room crowd to a 50-seat court-martial room at Fort Belvoir outside Washington, D.C., including defense lawyers from Guantanamo's Sept. 11 tribunal and prosecutors from the Abd al Hadi al Iraqi trial.

Because Congress has forbidden the transfer of detainees to the United States for any reason, each and every hearing has to be held at the base's crude Camp Justice compound.

It is not so in the al-Qosi case because, aside from the fact that he appears to have left home to join forces with AQAP in Yemen, the terms of his plea agreement forbid him from ever setting foot on U.S. soil.

In court, case prosecutor Michael O'Sullivan sought to question Lachelier about the unspecified conflict that precluded her from representing al-Qosi. To that, and a question about whether she had contact with al-Qosi since he left Guantanamo in 2012, she replied. "That would be privileged."

"The fact of any communication is privileged," she said, appearing to lecture O'Sullivan, who for a time was the acting Chief Prosecutor for Military Commissions. "Especially in this case."

O'Sullivan argued to Pohl that the three lawyers the Chief Defense Counsel had assigned to the fact-finding hearing _ Filbert, Schwartz and Navy Cmdr. Pat Flor _ were not entitled to receive evidence or act on al-Qosi's behalf because "they do not enjoy an attorney-client privilege."

To which Filbert replied: "We're properly detailed. We're ready to represent Mr. al-Qosi."

First, however, Pohl recessed to no set date to consult with the appeals court on what to do about the only lawyer in court who ever met the man whose case is on appeal, and who claims a conflict.