Survivors of Lake Alice’s notorious child and adolescent unit were disbelieved for years, while institutions were protected. David Williams reports

Lake Alice was a place of torture. Survivors of the child and adolescent unit, near Whanganui, have said it, former staff have said it, and private groups, who for decades have pushed for survivors to get justice, have said it since the 1970s.

How has the state, in its various forms, responded?

The Abuse in Care Royal Commission will hear the current narrative today, when Solicitor-General Una Jagose enters the witness box, on the penultimate day of its Lake Alice-specific inquiry.

Apologies from Police and the Medical Council have arguably put pressure on Jagose – whose department, Crown Law, has been accused of obstruction of justice – to expand on her statements of compassion and empathy given to the commission last year.

But there are many more questions to answer. The commission has taken statements and evidence from a wide variety of sources that show the state’s rejection of allegations emerging from Lake Alice, and its defence of those thought to be involved, started almost the moment the first stories of abuse came to light.

Oliver Sutherland, of the Auckland Committee on Racism and Discrimination, or ACORD – a Pākehā group formed to challenge institutional white racism and attitudes – was instrumental in stories from Lake Alice being made public.

On December 1, 1976, his group was approached by Lyn Fry, a Department of Education psychologist, about the mistreatment of a Niuean schoolboy, Hake Halo, at the child and adolescent unit.

ACORD’s Ross Galbreath wrote to Social Welfare Minister Bert Walker on December 13.

The letter said: “During the next 11 months he received forced medication by intra-muscular injection and about 10 treatments of electro-convulsive therapy (ECT). His family did not give their consent for this, nor were they ever told officially that it had taken place.”

The first story about the case, headlined ‘Boy’s shock treatment raises protest’, appeared in the New Zealand Herald on December 15.

Walker rejected ACORD’s claims in a Radio New Zealand bulletin on December 17. But there were multiple complaints raised from within the system.

Fry, who was the Psychological Service Association’s secretary, wrote to Health Minister Frank Gill, calling for a full inquiry into the use of electric shocks as punishment, saying there was no clinical justification for using them in that manner.

Also Craig Jackson, the Education Department’s district psychologist at Palmerston North, wrote to the department’s director-general RO Sinclair about children getting electric shocks. Sinclair wrote back telling him not to take part in inquiries or publicity, saying it was “entirely a medical matter”.

Undeterred, Jackson, as a concerned citizen, wrote to the Health Department’s director of mental health, Stanley Mirams, saying electric shocks from an ECT machine were used without pre-medication, and were “being used punitively”, with the majority of youngsters receiving treatment “without reference to their medical or psychiatric status, or grounds for admission”.

Jackson admitted he wasn’t medically trained but complained on humanitarian grounds, “and on the basis of common sense judgement it appeared to me at the time that unethical use was being made of this treatment”.

As ACORD’s Sutherland told the Royal Commission: “The Government knew, the people in positions of authority knew, and cannot say that they were unaware of this abuse.” His colleague, Galbreath, who wrote the 1976 letter to Minister Walker, added: “It wasn't shock treatment, it was shock punishment.”

In January 1977, Walker announced an inquiry by Magistrate William Mitchell. “This was the inquiry we thought we wanted,” Sutherland said a fortnight ago.

But the inquiry was held “in camera” – in secret, basically, without the public present – the terms of reference were limited, and it was not clear if anyone from Halo’s family was spoken to. The boy himself did not give evidence.

Lake Alice teacher Anna Natusch was an unintended whistleblower, detailing the punishment regime, including solitary confinement.

Mitchell’s report, completed in March of that year, was seen by ACORD as a whitewash. Walker said it “vindicated” his department. But Sutherland pointed out in his attempt to exonerate the Department of Social Welfare of wrongdoing, the magistrate could only find authority for treatment was “implied”. There was no express authority for shock treatment from department officers or the family. Obviously, the victims didn’t consent.

Mitchell was not persuaded the treatment was administered to cause “unnecessary” suffering. (Leeks claimed it rendered the patient immediately unconscious – something contradicted by multiple survivors at the time and before the Royal Commission.)

The unanswered question, wrote NZ Herald medical reporter Peter Trickett, was over the “degree” of suffering caused by administering electric shocks with the normal anaesthetic.

“We’d said to every authority that wanted to listen that what was happening at Lake Alice was absolutely unacceptable and that the only way to get to the bottom of it and to find out who was accountable was to have a Commission of Inquiry.” – Oliver Sutherland

Mitchell’s report found the shocks were necessary because of Halo’s “acute psychotic depression”. However, Trickett said this was contradicted by a letter from Lake Alice’s head child psychiatrist Selwyn Leeks, which said Halo was shocked because of his “apparently psychotic behaviour”.

The magistrate prickled at “protests from people with no direct interest in the case” – such as ACORD, and the Citizens Commission for Human Rights, which would, decades later, spearhead a successful case to a United Nations committee.

New allegations came to light, which were put to Mirams, the Health Department’s director of mental health. Two families of boys sent to Lake Alice said they received electric shocks on their knees as a form of punishment.

As Sutherland told the Herald in May 1977, if the new allegations proved correct “the misuse of shock equipment will constitute perhaps the most appalling abuse of children in the guardianship of the state that this country has known”.

Within days, Mirams said the ECT machine, which delivered the shocks, had been taken from Lake Alice. It would be “very difficult to envisage a defence “ to deliberately inflicting pain on different parts of the body, he told the Herald. Using shocks as aversion therapy on children “would be unthinkable”.

Mirams commissioned Gordon Vial, an Auckland lawyer and district mental health inspector, to investigate.

At the same time of year, Ombudsman Sir Guy Powles released his own report into the case of a 15-year-old at Lake Alice.

He found the boy’s detention unlawful, and there was little consideration as to whether he or his guardian consented to treatment. Shocks shouldn’t be given to a protesting patient, Powles said, and the shocks should only happen in exceptional circumstances, and with anaesthetic. The cumulative effect of the actions and decisions of the officers of departments of health and social welfare caused the boy a “grave injustice”, the Ombudsman found.

(Nurse Brian Stabb told the Royal Commission that an hour before the Ombudsman’s representative arrived at Lake Alice, Leeks “insisted” on shocking the boy in question. “As a result, [redacted] was not in a fit state to answer the questions of the representative.” After the report, Leeks called in to the unit, “saying he had put his affairs in order as he was expecting to go to prison”.)

Political reaction was swift, with Social Welfare Minister Walker accusing Powles of having “gone off at half-cock”. Jackson broke his silence and contacted Labour MP Jonathan Hunt, who called for immediate action on the Ombudsman’s report and a review of adolescent psychiatry.

In October 1977, the NZ Law Journal published an article headed ‘Children: consent to medical treatment’, written by Department of Social Welfare solicitor Rodney Hooker. It said: “There can of course be little doubt that medical treatment constitutes an assault upon the patient unless the patient consented to the treatment.”

The 1977 amendment to the Children’s and Young Persons Act included a clause requiring consent before psychiatric treatment.

Despite the media storm, Lake Alice was still operating.

Sutherland wrote to Mirams, only to find he’d already considered Auckland lawyer Vial’s report and the matter had been referred to police, over section 112 of the Mental Health Act, which related to the inhumane treatment of patients.

Mirams felt using electric stimuli as aversion therapy was “quite acceptable”, it emerged later. He only involved police to decide whether nursing staff were medically supervised and had authority to deliver shocks punitively.

ACORD wanted a Royal Commission – but it would take more than 40 years for one to be established. Sutherland told the commission a fortnight ago: “We’d said to every authority that wanted to listen that what was happening at Lake Alice was absolutely unacceptable and that the only way to get to the bottom of it and to find out who was accountable was to have a Commission of Inquiry.”

In January 1978, the Commissioner of Police said there was no evidence of criminal misconduct, a finding that would echo down the years, as no one has been charged for what happened at Lake Alice.

Even Sidney Pugmire, superintendent of Lake Alice Hospital, maintained in 1976 that Leeks, the children’s unit head psychiatrist, was “really answerable to himself”. (When the child and adolescent unit closed in 1978, Leeks moved to Australia. He took with him a Certificate of Good Standing issued by the Medical Council.)

Sutherland said the response of authorities not to hold any department or individual to account is now a matter for the Royal Commission.

“In ’77 we called the act of punishing children with powerful electric shocks to their body what it is, which was torture. We repeatedly drew attention to complaints of abuse and we repeatedly called for a full inquiry into these allegations. And so it can't ever be said, and maybe the Crown won't say it, that the people in power in the ’70s did not know what was going on at the time. They knew, because we told them repeatedly.”

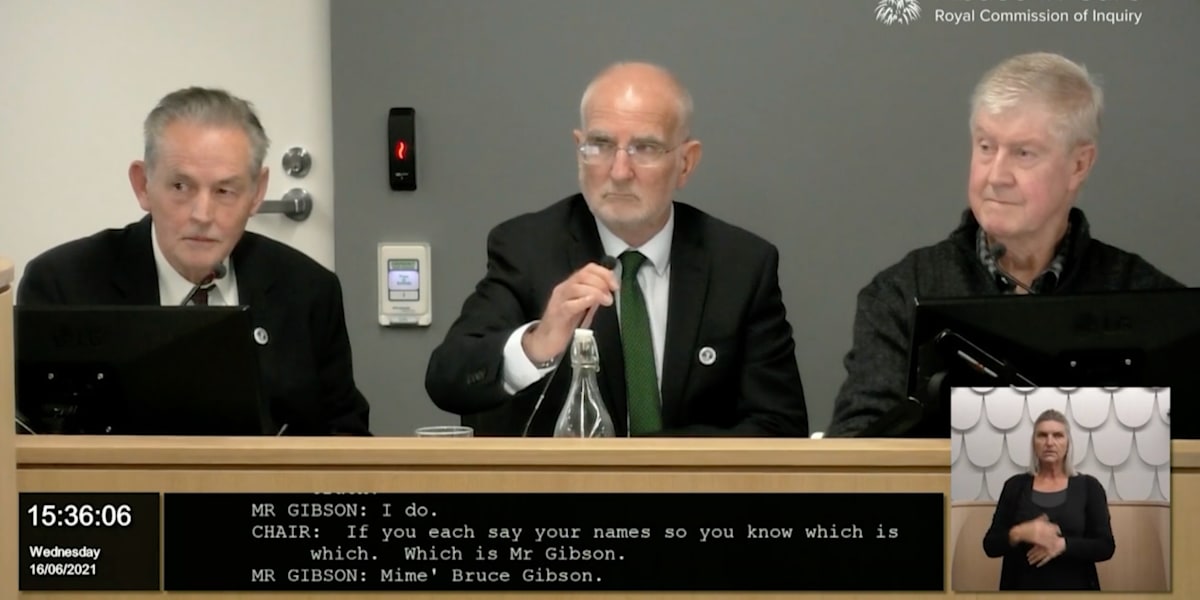

Another group to advocate for Lake Alice survivors is the Citizens Commission on Human Rights (CCHR), established by the Church of Scientology. One of its members, Bruce Gibson, described electric shocks to the Royal Commission.

Voltage, as high as 460 volts, creates an electric field in the patient’s skull, putting force on electrons inside the brain, causing them to move. “This shock to the brain causes a seizure and causes the patient to convulse.”

At Lake Alice in the 1970s it was meted out “unmodified”, without anaesthesia or muscle relaxant, on various parts of children’s bodies, including the genitals. A group from CCHR toured Lake Alice in August 1976, and its concerns were detailed in the Wanganui Chronicle two days later.

It emerged some years later, that a child at Lake Alice laid a complaint with Mirams, the director-general of mental health, in 1977. The complaint was sent to the Medical Council and reached its penal cases committee. It was also investigated by the Medical Association.

Medical Council documents show its central ethical committee chairman, W.J. Pryor, writing to Leeks in August 1977 to say punishing patients in psychiatric therapy was unacceptable.

“We appreciate that this could have been carried out by you in good faith at the time, but feel strongly that this constituted grossly unethical conduct likely to bring the reputation of the medical profession into disrepute.”

The records show Leeks never denied the allegation. He thought the association and council were wrong. His letter to the council in November said he involved five youngsters, the victims of assaults, in the “therapy of their attacker” – which meant administering electric shocks.

“The five boys were asked to tell [redacted] about what it was like for them in the recent assaults and their feelings now. At that point they turned the switch and gave [redacted] the faradic stimulus, I had a few words with [redacted] and the boy concerned, and the next one took over. They then left the room and I continued the treatment session as on previous occasions.”

(Note how this contradicts Leeks’ words from around the same time, that shock treatment rendered the patient immediately unconscious.)

Professor of Psychological Medicine F.J. Roberts told the Medical Council he disagreed with Leeks’ actions and didn’t agree with involving the boys in therapy. Victor Boyd, a volunteer researcher at CCHR, said the paperwork ended abruptly and it appeared the investigation was discontinued, with no findings “despite the bizarre nature of the case and the obvious departure from medical and psychiatric practice”.

After Lake Alice, Leeks ended up practising at a hospital in Victoria, Australia. Hunt, the Labour MP, presented a petition on CCHR’s behalf in 1979 for a commission of inquiry into the use of electro-convulsive therapy. This was rejected by the social services select committee.

The Nineties

Even in 1991, the Medical Practitioners Disciplinary Committee maintained there were no grounds for inquiry into the conduct of Leeks. It was during the 1990s that CCHR picked up the case of Leoni McInroe, who filed claims against Leeks and the Government.

Boyd said McInroe’s case, joined by another person who’s not named, were important. “They were the first filed legal applications claiming psychiatric abuse and naming Dr Leeks as the primary abuser. Because of the amount of money they were claiming, and the possibility of setting a legal precedent, their case was being watched closely by the government lawyers.”

In 1999, Leeks cancelled his registration with the Medical Council. This meant the council could refuse to investigate complaints against him. Boyd said it did just that when CCHR asked them to do so in 2012.

Last week, at the Royal Commission hearing, Medical Council deputy chief executive Aleyna Hall delivered an apology.

“We want to acknowledge the pain and suffering of all survivors who experienced abuse while in state care, including those at Lake Alice Hospital. The Medical Council acknowledges the hurt that you have experienced and apologises for any actions that the Medical Council of the time should have taken but did not.

“Due to the length of time that has passed since the complaints about Dr Leeks were made and the incompleteness of the records which are available, it is with regret that the current Medical Council is unable to provide reasons for the decisions that were made in the past in relation to complaints of abuse or in relation to Dr Leeks. The council accepts that some complainants have been dissatisfied and disappointed with those decisions and it sincerely apologises for any hurt that has occurred as a result.

“The current Medical Council of New Zealand has asked me to convey its clear and absolute position that it strongly condemns misconduct by any doctor that results in harm to patients or the public.”

The 2000s

In July 1997, a 20/20 TV current affairs programme on Lake Alice sparked a flurry of interest, prompting then Health Minister Bill English to say he was horrified.

Lawyers John Edwards and Grant Cameron gathered cases to turn into a class action, and negotiations with the Crown ensued. (Cameron told the Royal Commission he thought the Crown’s strategy in 1998 was one of delay “designed to ensure the claimants would run out of money and/or motivation and simply go away”.)

More media interest emerged in 1999, with The Press newspaper and Sunday Star-Times running stories. Later that year, Christchurch’s Cameron, who took over the class action, filed claims on behalf of 56 claimants. More joined later to bring the total to 95. The civil action resulted in an apology and ex-gratia payments.

In October 2001, it was announced $6.5 million would be paid as an out-of-court settlement. Boyd: “It should be noted that the Government had set aside $132 million for the Lake Alice cases a year before.”

An independent report on payouts to victims was written by retired High Court judge Sir Rodney Gallen, but, thankfully, he went well beyond his original remit. Crown Law tried to suppress his report, which had been leaked to the media, but lost the case. (A headline in The Press read: ‘Children ‘wept in terror’ over ECT’.)

Gallen was explicit in describing electric shocks on various body parts, including genitals. He concluded the abuse – electrocution, physical and sexual abuse – was “outrageous in the extreme”.

A second round of payments was considered in 2002. The Crown-funded lawyer was David Collins, who, interestingly, was the partner in the firm Rainy Collins Wright which represented Leeks in the case against McInroe. (McInroe signed a settlement in 2002, but wishes she hadn’t.)

CCHR’s current director, Mike Ferriss, said the Crown “acted in defence” of Leeks in the McInroe case, holding up her claim for nine years.

One second-round claimant, Paul Zentveld, sued the Government over having $35,000 of his settlement offer being deducted for administration and legal fees. He won, and all second-round claimants had their legal fees returned.

Second police investigation

Following the second round of payouts, CCHR submitted several Lake Alice cases to the police to investigate “ill-treatment and torture” and Cameron’s law firm submitted many more. The total was just over 40 complaints.

By 2006, the police investigation was languishing. Zentveld handed detective superintendent Malcolm Burgess his statement – prepared by CCHR because Leeks was being investigated by the Medical Practitioners Board of Victoria.

(The board amassed 39 against Leeks relating to his practice at Lake Alice, but Leeks resigned on the eve of the formal hearing and it never took place. Once again, serious allegations were made about the psychiatrist’s conduct towards children – charges that were not disproved – yet the victims were denied justice.)

It took until 2010 for police to make a decision on the case, which was not to take a criminal prosecution.

Burgess, who was promoted to assistant commissioner, said at the time there was insufficient evidence, which was backed by an independent legal peer review. "These events happened over 30 years ago. Some witnesses have died, others were unable to accurately recall events to the level of detail required, some records and original files that may have assisted the inquiry have been lost or destroyed."

Yet, as Boyd told the Royal Commission, it emerged later police interviewed some former Lake Alice staff, including an anonymised registered nurse who witnessed a boy, accused of sexual offences, being shocked on the genitals and thighs by Leeks. Burgess wrote in a job sheet: “The aversion therapy was applied as a punishment. The boy who had been offended against was invited to operate the apparatus. Other boys were also involved.”

Cameron, the Christchurch lawyer, criticised the decision, pointing to powerful documentary evidence. CCHR said some complainants weren’t interviewed.

Ferriss, the current CCHR director, told the Royal Commission: “Crown Law withheld from the police statements of Lake Alice staff it had obtained, which told us there was at least some collusion to make this investigation incomplete and inadequate.”

Police publicly apologised last Thursday.

Detective superintendent Thomas Fitzgerald, director of the Criminal Investigation Branch, said police didn’t give sufficient priority and resources to investigating the allegations.

“This resulted in unacceptable delays in the investigation. It meant that not all allegations were thoroughly investigated. The police wish to apologise to Lake Alice survivors for these failings.”

He said police were committed to ensuring it didn’t happen again.

Of 34 survivor statements given to police in 2002, 14 or 15 might have been lost. It was unlikely they formed part of the investigation. Many of the remaining 20 statements, which included allegations of sexual and physical assaults, were not saved and can’t be located.

After the police announcement in 2010 that the Lake Alice file would be closed without prosecution, Attorney General Chris Finlayson wrote to MP Wayne Mapp to say the Government did not intend to hold an inquiry into Lake Alice. Following the 2001 settlements, apology and payment, a more extensive inquiry wasn’t warranted, Finlayson said.

UN committee against torture

Five years later, CCHR’s then director Steve Green and Zentveld, travelled to Geneva, Switzerland, to meet members of the United Nations committee against torture. CCHR’s current director, Ferriss, told the Royal Commission the trip was “worthwhile” but more revelations were to come afterwards, when Zentveld asked for his police file.

One report from the file stated police considered his treatment could have resulted in charges – but police said it was too late to prosecute. That was the impetus for filing a complaint to the UN committee – seen as the last avenue to hold people to account for what happened at Lake Alice.

Its December 2019, the committee report found New Zealand’s response to torture allegations at Lake Alice were effectively a sham.

“At last we felt that finally here was an official body who was not only listening to us, but had taken a very strong stance against the New Zealand Government,” Ferriss wrote in his evidence to the commission. “The victims of Lake Alice who were alerted to this news were overjoyed by the decision, but were understandably cautious when it came to how the Government might respond to the UN’s demands.”

The Government responded a new police investigation had begun and the Royal Commission would make a case study of Lake Alice. The UN asked the Government to make its decision public and “disseminate its content widely”. All that happened, however, was a hyperlink was added to the police website, on the page devoted to the Royal Commission.

The UN committee says an investigation and prosecution of perpetrators is essential when there’s alleged torture. Yet many of the details – and belated apologies – over Lake Alice may never have emerged without the Royal Commission, more than 40 years after its child and adolescent unit closed.

CCHR said the truth about Lake Alice, drawn out by the commission of inquiry, is far worse than it imagined. Ferriss wrote: “What was administered to the children amounted to torture, using known torture techniques, under the guise of treatment at the hands of a registered psychiatrist inside a government-run psychiatric hospital. This should never have happened and it should never happen again.”

So many people within various agencies knew what happened but few raised concerns. Often, they were threatened or effectively silenced.

The latest police investigation is drawing to a close. But Leeks’ lawyer, Hayden Rattray, told the commission the 92-year-old – who has previously denied wrongdoing or professional misconduct – has prostate cancer, heart disease and possibly Alzheimer’s disease or dementia. “Dr Leeks is neither aware of the matters before the inquiry nor cognitively capable of responding to them.”

The public should soon know what that means for the renewed police investigation.

CCHR’s Ferriss said police have interviewed more than 100 former patients and several former staff. “We are anticipating that this investigation will establish the facts of Lake Alice and the alleged incidents of torture and hold those responsible accountable. The survivors of Lake Alice expect nothing less.”