Fraud in America has stopped being a slow leak and turned into a flood. It's touching bank accounts, businesses, payroll departments, retirees, college students, city governments, and people who were certain they would never fall for it. The crisis is not that scams exist. The crisis is that we still believe they only happen to someone else.

I have spent my career studying criminals, investigating fraud, and teaching the public how manipulation works long before anyone realizes they are in it. But the threat today is evolving faster than public awareness, corporate training, or public policy. And while we debate markets, elections, and foreign interference, Americans are losing billions to something far quieter, far smarter, and far more personal.

According to the Federal Trade Commission, Americans reported losing $12.5 billion to fraud in 2024, a 25% increase from the year prior, and the majority of losses came from imposter scams. That number alone should qualify as a national emergency. And while individual financial loss is devastating, the corporate version can be catastrophic. Business Email Compromise (BEC), one of the most effective and least reported corporate scams, cost organizations $2.9 billion in 2023.

When people hear "scams," they imagine typos, bad grammar, clumsy emails, and poorly designed websites. As scammers often operated from overseas and mass-distributed their schemes, mistakes were their signature. That used to be true, but not anymore. Artificial intelligence erased that weakness. Today, phishing emails are grammatically pristine, polished, persuasive, and indistinguishable from legitimate corporate communication.

Even voice, once the most trusted identifier of all, is no longer safe. AI can now replicate tone, cadence, accent, breathing patterns, and inflection well enough that parents believe they are speaking to their children, and employees believe they're speaking to their CEO. Urgency-based deception has gone from convincing to personalized.

Recently, a local business owner near me was instructed to send $4,500 in Bitcoin to pay an outstanding utility bill. She complied, terrified of the alternative, until she realized something was wrong. Her story is now one of recovery. Most aren't. But here's where the crisis deepens. When a person falls for a scam, we blame the victim. When a business gets scammed, we fire the employee who fell for it. Neither solves the problem, and the fraud continues.

Consider a real case in New Hampshire, where scammers stole money through fraudulent emails and converted the funds to cryptocurrency. The payment, $2.3 million, was real. The breach triggered investigations, public scrutiny, and a familiar response: focus on individual fault instead of systemic failure.

In most cases, the organization fires the employee who made the mistake of falling into the trap of the scammers. What happens next? The remaining employees freeze. No one makes a decision. Every task stalls at someone else's desk. Fear replaces judgment, and escalation replaces responsibility. Fraud doesn't stop when you fire one person. It stops when you educate all of them.

That same principle applies at home. Telling a parent, spouse, or friend, "Don't fall for scams," is like telling someone, "Don't get sick." Awareness prevents nothing without education. The most effective intervention is not a warning; it's exposure. I tell families: print the articles, leave them on the counter, casually place them on the coffee table. Let evidence do the convincing, not emotion. Because shame thrives in silence, and scammers thrive in shame.

People don't report fraud because they are embarrassed, and they are embarrassed because we treat victims like failures instead of targets. In my years interviewing victims during fraud investigations, the answer to the question "How much did you send?" is almost never the first number they give due to the embarrassment factor. The real number comes later, heavier, softened by humiliation. Scammers know this. It's part of their math.

So here is the truth we are avoiding: fraud is no longer a crime of opportunity, it's a crime of strategy. It now borrows from psychology, technology, urgency design, social trust, biometric mimicry, and behavioral economics. The only outdated component is our defense.

Businesses must move from reactive punishment to proactive training. If you are not regularly educating employees on modern fraud vectors, payment manipulation, social engineering, phishing evolution, AI impersonation, wire diversion, or verification protocols, you are running your business on digital trust alone and hoping for the best.

Individuals must do the same. Not with panic, but with literacy. Fraud literacy must become as basic as password hygiene and two-factor authentication. The question is no longer "Can this happen to me?" The question is "How prepared am I when it does?"

Fraud doesn't always grab attention like a dramatic market crash or geopolitical conflict. Fraud is quiet, human, emotional, engineered, and unrelenting. That's why it spreads undetected. That's why the damage compounds. And that's why it is America's silent epidemic. We talk about crime, inflation, data breaches, and economic stress. But no crisis is draining more wallets, dismantling more trust, or evolving faster than financial fraud. The country is not ignorant of its existence. We are numb to its proximity.

The scammers are not waiting for better technology. They already have it. They are waiting for better timing, better pressure, and the moment someone thinks, "This won't happen to me." That moment is their starting line.

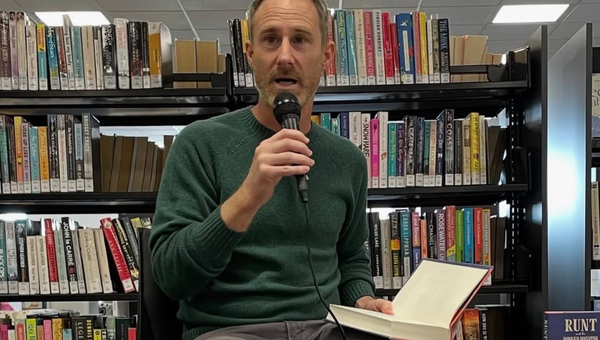

About the Author

Mike McCall is a retired FBI Special Agent and former IRS—Criminal Investigation Division Special Agent specializing in complex financial crimes and forensic accounting. He serves as an educator at Boston-area universities, including Boston College and Stonehill College, where he teaches fraud prevention and financial crime investigation. McCall is also a trained volunteer with the AARP Fraud Watch Network and works directly with businesses to develop fraud prevention strategies, employee scam-awareness training, and organizational risk mitigation. He is the founder of MPM Consulting LLC, an accounting practice in Bridgewater, Massachusetts, focused on helping companies and institutions detect, prevent, and respond to financial fraud.