As countries mark World Day Against the Death Penalty on Friday – a day after France honoured Robert Badinter, the man who ended it in the country – experts say capital punishment is still failing to stop crime and instead fuels violence.

On 17 September, 1981, Badinter, then France’s justice minister, stood before the National Assembly and declared: “Those who believe in the deterrent effect of the death penalty misunderstand human nature."

Badinter, who was inducted into the Panthéon in Paris on Thursday, was unwavering in his conviction that the fear of dying does not stop people from killing.

And yet, 44 years later, the debate rumbles on. More than 50 countries retain the death penalty, often using the argument that it deters violent crime. But that claim, say many experts, doesn’t hold up.

Robert Badinter, who ended France's guillotine era, enters the Panthéon

The myth of deterrence

“If anything, the numbers tell the opposite story,” says Alain Blanc, former president of the French criminal high court and vice-president of the French Association of Criminology.

“After abolition in France, we didn’t see any increase in crimes that had previously been punishable by death and were now punishable by life imprisonment.”

Data from elsewhere supports his view. In Canada, the homicide rate has dropped from 2.8 per 100,000 people in 1976 – the year the death penalty was abolished – to 1.91 in 2024, according to Statistics Canada.

In the neighbouring United States, 27 of 50 states retain capital punishment, and the homicide rate is higher in those states. In 2020, the homicide rate averaged 7.5 per 100,000 in “retentionist” states, compared to 5.3 in abolitionist ones, according to FBI crime reports.

"The death penalty rests on the idea that once people know they risk execution, they’ll stop committing crimes. But if every criminal thought rationally about the risks, there wouldn’t be many crimes to begin with," Blanc told RFI.

'A culture of violence'

Researchers also point to the idea that the death penalty in fact reinforces the idea that violence is an acceptable response to wrongdoing.

Raphaël Chenuil-Hazan, executive director of the NGO Ensemble contre la peine de mort (“Together Against the Death Penalty") notes that countries which still practise executions often share a “culture of violence”.

“I’m not saying the death penalty creates crime,” he explained to RFI, “but it perpetuates it. It stems from the same culture – that of vengeance, of weapons, of taking justice into one’s own hands.”

Once that mindset takes hold, he warns, society begins to see state-sanctioned killing as normal. “The death penalty sends the message that the ultimate act of violence – cold, calculated killing – is legitimate.”

Fighting to end death penalty worldwide 40 years after its abolition in France

The absence of reason

The deterrent argument also collapses when you consider that most perpetrators of violent crime act under extreme emotional pressure or psychological distress, experts argue.

Chenuil-Hazan told RFI: “When you study violent crime it becomes clear that fear of death plays no role. You generally find three types of criminals: the psychotic – such as serial killers or terrorists – for whom fear of death is irrelevant; the opportunist, who doesn’t plan ahead; and organised crime, where it’s all about money and power, not fear.”

Crimes of passion or impulse, he adds, are ruled by emotion, not logic.

Political scientist Sébastian Roché, research director at the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS), agrees. “What characterises violent offenders is their lack of self-control. They’re not capable of regulating their behaviour or calculating risks.”

Anne Denis, who heads Amnesty International France’s death penalty commission, echoed this argument, saying: “No criminal commits a crime believing they’ll definitely be caught and sentenced to death."

Politics and punishment

Still, executions persist. Last year they were recorded in 15 countries, with 1,518 people put to death according to Amnesty International's 2024 report.

This was a 32 percent increase from 2023, marking the highest number of executions since 2015.

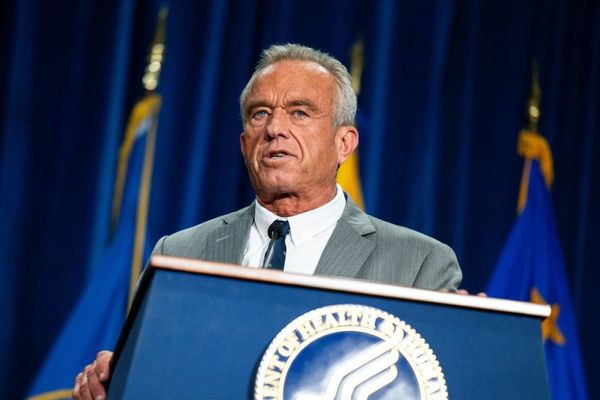

In the US, President Donald Trump declared last December that once he was inaugurated for his second term he would "direct the Justice Department to vigorously pursue the death penalty to protect American families and children from violent rapists, murderers, and monsters".

When he took office on 20 January, one of his first orders was to "restore" the death penalty, following his predecessor Joe Biden's moratorium on executions.

On Friday, Roy Lee Ward, a 44-year-old who has spent more than 20 years on death row, is due to be executed in Indiana – the state’s third execution in less than a year. Seven more executions are scheduled for this month.

According to Denis, Trump’s stance allows him “to avoid creating proper social systems and psychological support for disadvantaged communities”, members of which make up the overwhelming majority of death row inmates – 95 percent, according to the Equal Justice Initiative NGO.

Iran executed record 834 people last year, according to rights groups

However, political use of the death penalty is not confined to the US. “If you want to legitimise an iron fist, people need to be afraid,” explained the CNRS's Roché.

In Iran, Amnesty International reports, the authorities use executions as a tool of political repression, targeting dissidents and minorities – particularly Kurds and Baluchis.

“In China,” added Chenuil-Hazan, “it’s a way for President Xi Jinping to clear the field around him and show who’s boss.”

Last month, China's former agriculture minister Tang Renjian was sentenced to death for corruption. While China continues to execute people every year, the exact numbers remain a state secret.

“People want to believe there’s a simple solution to crime,” says Chenuil-Hazan. “Execution feels cheap and easy. It saves us from having to think about prevention policies, which are complicated, expensive and take time to work.”

This article has been adapted from RFI's original version in French.