Repression at home, assertiveness in disputed territory on its doorstep, and expansion of soft power, economic and technological influence worldwide have all become hallmarks of confident China in the 21st century.

Last month, Beijing suspended a liberal law professor who openly criticised President Xi Jinping as the crackdown on dissent gathered momentum. Abroad, it is pressing ahead with plans for an "island city" in the South China Sea. An attempt by a Vietnamese naval ship to prevent a Chinese crew from setting up an oil rig in disputed waters nearby led to a collision and diplomatic finger-pointing.

Back on land, a US$7-billion railway link to Laos is almost half-finished and scheduled to begin service in 2021, even if it goes no farther than Vientiane. The onward link via Thailand has gone nowhere so far, as Thai authorities have been valiantly resisting numerous Chinese demands, something impoverished Laos was in no position to do.

Farther afield, meanwhile, Italy became the first Western European nation to sign on to the Beijing-backed Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) during President Xi Jinping's visit to the continent two weeks ago.

During his time in Europe, President Xi also signed 15 business deals totalling US$45 billion with France, including an order for 300 Airbus planes. The deals represent a huge setback to the United States where its aviation champion, Boeing, is facing severe backlash from two tragic plane crashes that appear linked to shortcomings in its advanced technology.

Meanwhile, the Chinese communication technology jewel Huawei, arguably the world leader in 5G systems, is making huge inroads into Africa, even as Washington pursues a campaign to discourage its allies from using Huawei hardware on security grounds.

At home, China is now making its own passenger jets with the C919 seeking to one day rival Airbus and Boeing. Digitally, WeChat, Alibaba and others have built IT empires that rival the likes of Amazon and Facebook.

THREE-WAY RIVALRY

In Southeast Asia, it could be argued that China now sets the agenda, mainly due to its role as a major trading partner and also because of its military adventurism in the South China Sea. Beijing's outsize influence is a growing concern for countries in the region that want to remain on good terms with three major powers: China, the United States and Japan.

"There is a great rivalry between the US, China and Japan in Southeast Asia," says Ernesto Braam, a regional strategic adviser for Southeast Asia and governor of the Asia-Europe Foundation Singapore.

The significance of the BRI in the context of the US-China rivalry in Southeast Asia depends on whom you ask. Beijing can be seen as having economic, geopolitical and normative motives.

"If you talk to an economist, he will explain the BRI in economic terms. If you talk to an international relations specialist, he will say everything is geopolitics," said Mr Braam.

Beijing has said it wants to develop the western region of China, with a link from the Singapore-Kunming railway running through that part of the mainland and beyond to Central Asia and Europe.

The BRI was earlier seen as a counterweight to the US-initiated Trans-Pacific Partnership, which was the centrepiece of President Barack Obama's strategic pivot to Asia before Mr Trump withdrew from the 12-nation trade agreement in 2017.

Another argument is that China has been forced to do something about its industrial overcapacity by cementing export deals to countries selected for BRI projects.

Then there is the argument that China is using the BRI to recycle its current account surplus in a way that generates or creates more revenue, such as through higher interest. But experts say this is "complete nonsense" because China's current account surplus is actually going down, Mr Braam said.

"What you hear the most from China is that the BRI is a 'win-win' which is the normative side of things … but this is always a mixed package," he said.

The fact is, most of the countries where BRI projects are planned or under way worry about ending up as losers, especially if they have to shoulder heavy debts for big infrastructure projects.

In the Philippines, for example, critics of President Rodrigo Duterte say he has agreed to unfavourable terms for China-funded infrastructure dams, roads and railways. An opposition senate candidate has accused the administration of concealing the loan terms for another China-backed dam signed last year.

Similar complaints have been heard from other Asian governments or their political opponents, from Malaysia to Pakistan, that have signed onto BRI projects.

Mr Braam said perceptions that the BRI represents an instrument for influencing governments has led to some "pushback", and a slowdown in the pace of Belt and Road developments in Southeast Asia.

"Even if the BRI is not challenging your country's interests, you can see it happening in other countries and that sort of scares you, where people are talking about Sri Lanka, so everyone has been warned now, and it took a few years, and we see some pushback against that," he said, referring to the debt trouble facing the South Asian nation.

In Southeast Asia, he said, the pushback has taken the form of regulations that are less investor-friendly. It is becoming "very difficult to cut through the red tape where Chinese companies and the government are frustrated at the slow pace at which the BRI is moving".

In Malaysia, meanwhile, Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad took the dramatic step of pulling his country out of three BRI projects -- the East Coast Rail Link and two gas pipelines -- saying it could not afford them.

"Prime Minister Mahathir's decision was a big signal and all countries in the region are talking about it," Mr Braam commented.

Beijing is getting the message, with Chinese think tanks close to the government acknowledging that the process needs to be "less top-down and more consultative".

"This means not just signing a contract with another government but also consulting with the local people on the impact of the projects, which is what I heard during my visits to Beijing and Shanghai in December," he said.

Chinese contractors, notably on railways, are being prodded to employ local people, encourage the transfer of knowledge and be more aware of the environmental impact of their work.

"The only downside of that is that you cannot work as fast as before," said Mr Braam. "The big advantage of China in infrastructure projects is that they can do it extremely fast because they have a set format, even down to the specifications for a certain type of bridge, regardless of how wide the river is."

For a Chinese infrastructure project, everything is standardised, and contractors also benefit from a labour pool that has worked on thousands of kilometres of lines in China. Having to slow the pace to consult with local people or hire more local workers will require a change in mindset.

"With the change in the way things are done, the BRI projects will be slower but better received in the long term," he said.

"If we can all sit around the table and together draw up a plan, seeing who does what, then it would work fine as companies and labourers in the recipient country will play a role through contracts."

Another brake on the rapid rollout of BRI projects exists in the form of budgetary constraints at home. Credit for certain BRI projects is becoming harder to obtain, and sourcing foreign currency outside the mainland is also hard. From an economic and fiscal standpoint, China has to watch out for "imperial overstretch", Mr Braam says.

"They have to be careful as there are some questions inside the country about why all this money is being invested abroad and not within China itself, where the leader has promised to change the economy from export-driven to more consumption-led and services-oriented," he said.

"There are some big issues inside China that could influence the BRI that many people are not looking at, as they are only seeing pushback from the outside. But there are domestic issues that might change the direction of BRI including the finances. Can they sustain this when the current account surplus is diminishing while there are bubbles within the economy?"

The near-term outlook for trade is another big question mark for China, as it seeks to reach a lasting agreement with the United States and put an end to current tensions that have involved the weaponisation of tariffs.

If trade tensions between the US and China remain or deepen, export growth in Asia Pacific may slow to 2.3% in 2019, while import growth may drop to 3.5%, says the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (Escap). This could lead to stagnation in China's real exports and a further slowdown in its economy.

MARITIME MEDDLING

Turning to the South China Sea, where China has been absolutely brazen in its assertion of territorial claims that absolutely no one else supports, Mr Braam says the perception might be that the US is withdrawing from Southeast Asia, but in reality it is not.

"The US Navy is there, the troops are still there, the bases are still there and they are not being withdrawn at all," he said. "But perception does matter because it gives you the basis of the influence you can wield in the region."

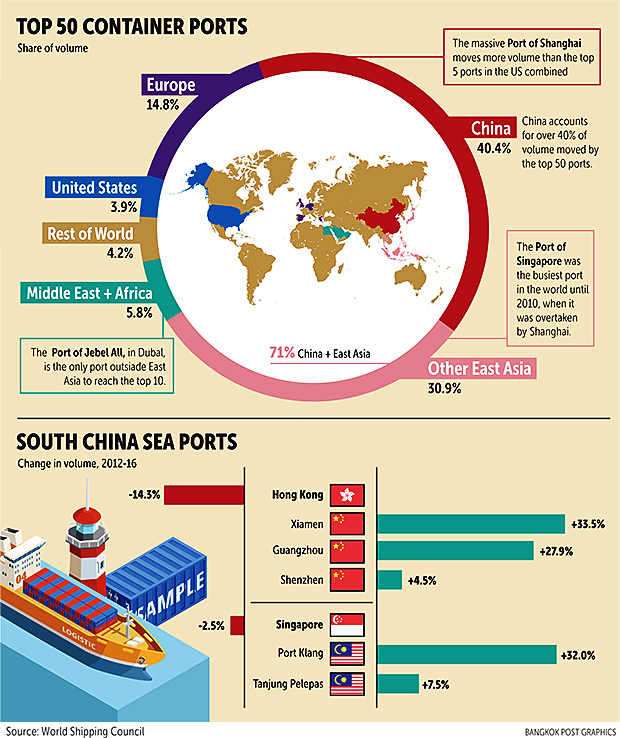

Ninety percent of world trade is handled by maritime shipping and 15 of the world's 20 busiest ports are located in East Asia. That means that the South China Sea will only become more important as a shipping route.

This realisation will embolden China to continue with its building programme on disputed islets and shoals, some of which are now home to a formidable array of military facilities. The southernmost legitimate Chinese territory in the South China Sea, Sansha, is now pressing ahead with a plan to build an "island city" on Woody Island and two neighbouring islets in contested waters.

Songsak Saicheua, a member of the advisory board at the Thammasat Institute of Area Studies, told a recent seminar that congestion in the Strait of Malacca, one of the seven biggest chokepoints in the world, will make the South China Sea even more contested.

"More than 50-60% of all the oil from Middle East passes through the Strait of Malacca to come to Asia Pacific, so even if China tries to look for alternatives via the BRI, the strait is still very important," he said. "That is why Beijing has stressed the importance of the South China Sea because it is an important sea lane for them."

On that note, the US has increased the frequency of what it calls "freedom of navigation operations" in the Pacific Ocean and the South China Sea by sending aircraft carriers and destroyers into the region.

It is hard to see where all this might end up, but Mr Braam foresees the US and China continuing to compete on all fronts, while the best thing for Southeast Asian nations is not to choose sides and to support international rules of trade and diplomacy.

"What we need is a rules-based international order and to realise that we have to get together, regardless of whether we like each other or not, as we have to concentrate on international reality and intraregional interests," he said.

"We have to make sure that there are rules and the rules are fair for everyone where China and the US have great power and the tendency not to follow the rules … and Asean has a big interest in these rules because they can protect them from pure, unrestricted raw power."