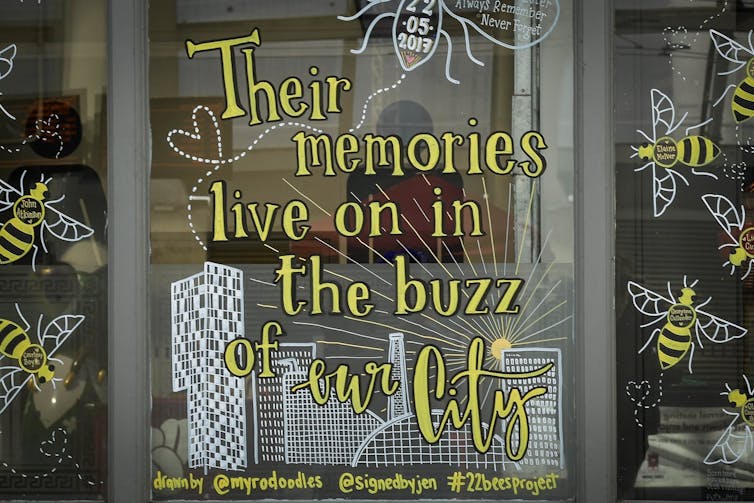

If you visit Manchester, one of the first things you’ll notice is the great number of bee images throughout the city. Born in the Industrial Revolution, the “worker bee” symbol captured the northern English city’s tireless spirit and its legacy as a buzzing hive of industry. Today, the symbol is more often associated with collective resilience and remembrance following the Manchester Arena attack on May 22 2017.

The bee became a powerful symbol of the “Mancunian spirit”, emerging almost instantly on murals, on bodies as tattoos and on public memorials. Over the last eight years, it has become a core part of Manchester’s identity.

As part of my ongoing PhD research, I set out to understand why the bee is everywhere in Manchester and what it means to people. I interviewed 24 Mancunians who were living in the city at the time of the attack, including some who were directly affected.

Conducted in 2023, seven years after the attack, these interviews aimed to capture how the symbol’s meaning had evolved as the city continued to process and commemorate the event.

For many, the bee still stands as a symbol of resilience, a reminder of how the city came together in the face of tragedy. But for others, its presence throughout Manchester has become more of a burden than a comfort.

Appearing on buses, shop windows and public spaces, it serves as a constant and eerie reminder of the events and aftermath of the attack. Eight of my interviewees described these as memories of “trauma”. Over time, what once felt comforting has become more unsettling.

Fifteen of my interviewees expressed discomfort with how the bee has become more commercialised in the years since the attack. Some described feelings of “exploitation”.

Both independent businesses and large companies have embraced the symbol, integrating it into their branding in public spaces. Many sell bee-themed gifts and souvenirs, such as fridge magnets, coasters and beanies.

Manchester city council has played a key role in this commercialisation, promoting the image through various initiatives, including the Bee Network transport system and the Bee Cup – a reusable takeaway cup launched in 2023.

In June 2017, shortly after the attack, the council moved to trademark several versions of the bee as an official city symbol. This was made public in March 2018, after the period for objections had passed.

Initially, the council allowed people and businesses to use the symbol for free, but later introduced a licensing scheme. Now, anyone wishing to use the trademarked versions of the bee must apply for permission from the council, and commercial use comes with a £500 fee. Businesses that want to use the bee are also asked to donate to charity.

The council described the trademarking of the bee symbol as a way to protect its use and support local good causes, such as the We Love MCR Charity, which helps fund community projects and youth opportunities across the city.

But some of my participants noted that this transformed the bee from something personal and meaningful to something more corporate. In their view, it is as if the city itself is commodifying the attack rather than honouring it.

This can be viewed as an element of “dark tourism”, which involves visiting places where tragedy has been memorialised or commercialised. In Manchester this manifests not through visits to the attack site but through the bee symbol, which has been commodified in murals, merchandise and public spaces. Tourists buy into collective grief through consumption, turning remembrance into a marketable experience and the bee as a managed and profitable commodity.

Some Manchester Arena bombing survivors I spoke to feel that their personal grief has been repackaged into a public identity, one that does not necessarily reflect the complexity of their experiences.

The use of the bee in products and souvenirs raises questions about how the city commercialises its identity, especially when considering the layered histories that the symbol carries.

Uncomfortable history

For some, the discomfort around Manchester’s bee goes even deeper. Today, the bee symbolises resilience and unity, but it originally represented hard work during Manchester’s industrial boom.

This era wasn’t just about progress — it also involved exploitation and colonial trade especially through cotton produced by enslaved people in the Americas. Manchester’s role in the industrial revolution would have never been possible without slavery.

My participants pointed out this hidden history, noticing that these stories rarely appear in Manchester’s public commemorations in the city. The bee’s visibility today reveals how cities tend to highlight positive histories, while uncomfortable truths remain hidden.

Focusing solely on resilience risks creating a simplified version of Manchester’s past. This can exclude some people in the present, overlooking how historical injustices, like the city’s links to the transatlantic slave trade, still shape their lives today.

This selective storytelling makes it harder for some communities to commemorate Manchester’s identity. They can’t do so without acknowledging past legacies of slavery and the city’s history of division.

While some see the bee as a proud symbol of unity, others feel it erases their history. As the bee continues to dominate public spaces, Manchester faces an important challenge: making sure this symbol genuinely acknowledges the varied experiences and histories of all residents.

This might be through dedicated plaques or exhibits that explore some of these hidden histories, and the bee’s complex meaning. Only by confronting its past can the city ensure that commemoration includes everyone.

Ashley Collar receives funding from ESRC (Economic Social and Research Council) as part of her PhD Doctoral Scholarship.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.