Fittingly, there were a lot of lessons from the longest World Series Game 7 in 101 years (11 full innings) and the longest World Series in 113 years (146 innings). Here is what we learned:

1. Nobody trusts their fastball

We know fastball usage has been declining even as velocity has risen. Only a decade ago, fastballs were the foundation of pitching. Technology (high speed cameras, spin tracking, etc.) has changed the foundation of pitching to the Three S’s: spin, shaping and sequencing. Regular season fastball use (not including cutters) dropped from 56.8% in 2015 to 47.4% in 2025, the lowest in recorded history (and, logically, all time).

The World Series brought the rise of secondary pitches to new heights. The desire to pitch away from slug meant a heavy dose of breaking pitches and splitters. The Dodgers and Blue Jays combined to throw the lowest rate of fastballs in a World Series since such pitch tracking began in 2008 (and, most likely, ever). And it wasn’t even close:

Lowest fastball usage in the World Series, 2008–25

In just 12 years the World Series fastball rate dropped from 61.3% (Red Sox and Cardinals) to 41.9%.

The lowest fastball usage by any team in a World Series belongs to the 2025 Blue Jays. Second lowest? The 2025 Dodgers.

Lowest fastball usage by team in World Series, 2008–25

It’s hard to argue with the results. Batters slugged .451 against fastballs in the World Series and .331 against everything else.

2. Never throw a strike-to-strike slider on 3-and-2

Righthander Jeff Hoffman was two outs away from closing the Blue Jays’ first World Series title in 32 years. Bases empty, top of the ninth, up 4–3. The No. 9 hitter, Miguel Rojas, at bat with Shohei Ohtani on deck.

The count went to 2-and-1. Hoffman threw a sinker away, which Rojas fouled, followed by a 96 mph four-seamer away, which Rojas also fouled. Hoffman tried a slider. It was a lousy one, a non-competitive backup slider that created a full count.

Uh oh. Hoffman knew there was no way he could walk Rojas, which would bring Ohtani and his 63 home runs to the plate as the go-ahead run. The lousy slider put him in a position where he had to throw a strike.

What pitch should Hoffman throw in a situation where he had to throw a strike? Fastball? Good choice. Hoffman throws his four-seamer more than any other pitch. Since Sept. 16, Hoffman had thrown 104 fastballs and given up one hit, a single. Hitters were 1-for-21 (.048) against his four-seamer over the past six weeks.

Hoffman throws 96 mph. Rojas had not hit a home run off a four-seamer thrown that hard in six years (Sept. 3, 2019), hitting .207 against 555 such heaters. He has no power against velocity.

But remember, nobody likes their fastball these days. Hoffman and Alejandro Kirk decided on a slider, which is Hoffman’s best pitch in terms of run value. Spin, spin, spin. That’s the way the game is played these days.

But this was not the time, not when the pitch had to be in the zone. Spin is fine at 3-and-2 when you can accept the consequence of a walk. The strike-to-ball slider may get you the chase swing. If it doesn’t and it’s a situation in which a walk does not hurt you, that’s fine. Play on.

In this case, Hoffman could not afford a walk. He had to make sure he was in the strike zone with his breaking pitch. A repeat of his previous slider would be an unforgivable mistake. And so, Hoffman guided his slider into the zone.

Hoffman had opened the seven-pitch sequence with a slider and obtained a swinging strike. But this slider, thrown too carefully, had 300 fewer RPMs, three inches less vertical drop and three inches less horizontal break. In layman’s terms, it was a hanger. It was the only pitch Rojas could have hit for a home run.

Middle-in. Home run. Tie game.

As much as teams love spin, a middle-velocity breaking ball is a worse pitch than an old-fashioned fastball when you must throw a strike:

Slugging vs. in-zone pitches, 2025

Hoffman had not allowed a home run on a 3-and-2 pitch over the past two years. The last one? Game 2 of the 2023 NLDS for Philadelphia in Atlanta. Pitching the bottom of the eighth with a 4–3 lead and a runner at second, Hoffman yielded a home run to Austin Riley.

The pitch?

A 3-and-2 strike-to-strike slider.

3. Be bold

The Blue Jays put the tying run on third base with one out in the bottom of the 11th, thanks to a double by Vladimir Guerrero Jr. and a sacrifice bunt by Isiah Kiner-Falefa. Dodgers pitching coach Mark Prior visited pitcher Yoshinobu Yamamoto on the mound. He ordered Yamamoto to pitch around Addison Barger to set up a double play. Unlike Toronto reliever Seranthony Dominguez, given the same instructions by his pitching coach in Game 3, only to throw a first-pitch cookie to Ohtani for a game-tying home run, Yamamoto has the command to execute. He threw four straight balls. Barger did not bite and walked.

Kirk was up next. A ground ball and the Blue Jays would lose the World Series. Kirk is among the slowest runners in baseball. The average MLB hitter grounds into a double play when the opportunity is present 9.8% of the time. Kirk is almost twice as likely to ground into a double play: 17.8%.

Yamamoto throws ground balls 53.7% of the time, well above the MLB average of 44.2%.

There was one sure way to avoid the double play: send Barger, a plus runner, on a steal attempt.

Dodgers manager Dave Roberts was in a bind. The tying run was on third base. If Barger ran and Roberts elected to throw through, the Dodgers would be vacating an infield position, most likely second base. That would open a huge hole for Kirk, one of the best contact hitters in the game.

Roberts’s priority was to defend the potential tying run on third base. It would be hard to swallow allowing the tying run to score by creating a hole in the infield. Moreover, any mishandling of a throw to second base could send Guerrero home. Most managers would not defend the stolen base there.

There was one way to find out: Barger should make a false break toward second on the first pitch to see if Mookie Betts or Rojas, the middle infielders, broke for the bag.

Barger took a short lead off first base and stood upright, his body language giving every indication he was staying put. And he was. No false break. The Dodgers had nothing to worry about.

Yamamoto did his usual expert job of getting the hitter off balance by changing speeds: 93-mph cutter (foul), 80-mph curveball (swinging strike) and 92-mph splitter (yes, a double play grounder). Barger never changed his lead or stance, never drawing a throw.

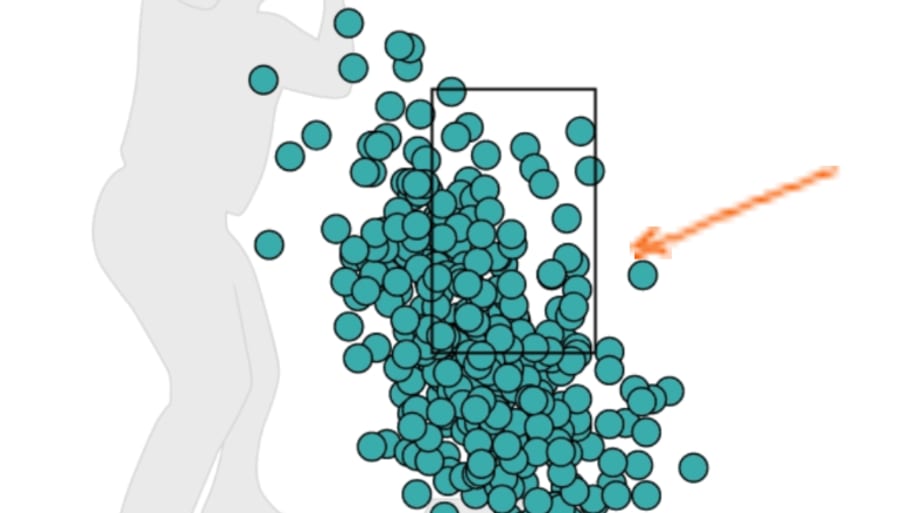

Kirk gave a halting swing at the last pitch, breaking his bat while pounding it into the ground, eight feet from the plate on its first bounce. If he was fooled, it was easy to understand. Yamamoto almost never throws his splitter away to righthanded hitters. Here are all 360 splitters Yamamoto threw to righthanded hitters this year. The arrow points to the one he threw to Kirk, one of only four all year in that middle-away box when you cut the zone into nine equal boxes.

The greatest fear managers have in sending the runner in this spot is the line drive double play. Too risky, right?

Well, let’s define risk. MLB hitters took 3,936 at-bats this year with runners on first and third and one out or less. How many times did the hitter line into a double play? Thirty-three. That’s fearing something that has less than a 1% chance of happening, as opposed to the 17.8% chance that Kirk will ground into a double play.

Sending Barger was more about being smart than being bold.

4. Inches matter

Kiner-Falefa is taking far too much heat for not scoring what would have been the winning run in the ninth inning on a ground ball to second by Daulton Varsho with the bases loaded and one out. Rojas threw to catcher Will Smith for the force out—barely. Kiner-Falefa is not totally blameless, but you must understand the full context.

a. Yes, his primary lead was too short.

“They told us to stay close to the base,” Kiner-Falefa told reporters, referring to the dugout and third base coach Carlos Febles. “They don’t want us to get doubled off in that situation with a hard line drive.”

He is 100% correct about that approach. Contrary to public opinion, you do not go as far off the bag as the third baseman is playing, not with one out when a line drive could end the inning.

With a lefthanded batter in the box, third baseman Max Muncy was playing 15.2 feet away from the bag, according to MLB’s player tracking data.

Standard procedure in this situation—one out, bases loaded, protecting against the line drive double play—is to go off the bag equal to two-thirds the distance that the third baseman is off the bag.

Kiner-Falefa should have been 11.4 feet off the base. He was 8.6 feet off the bag, according to MLB’s player tracking data.

That was his fatal mistake. A short lead is proper in that situation, but his mistake was that, under Febles’s instruction, he over-corrected. He had another two to three feet to take to be safely off the base without risking getting doubled up on a line drive.

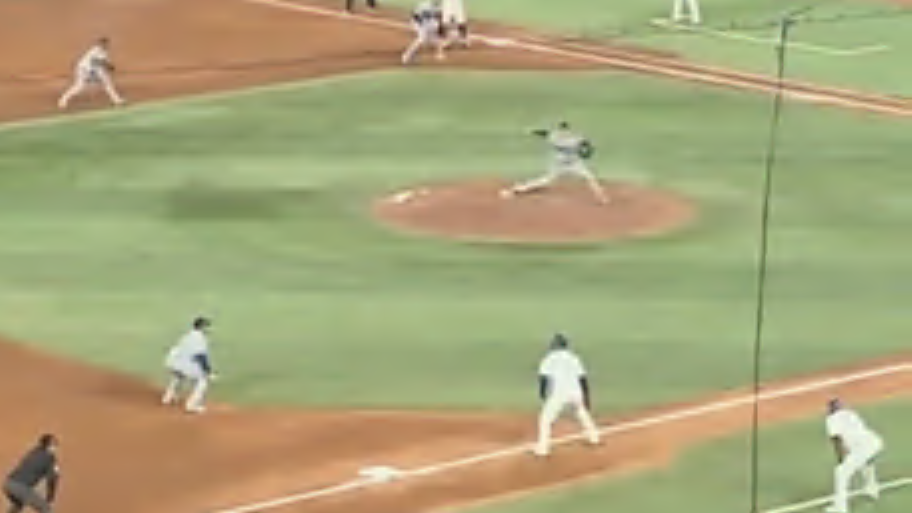

Cell phone video shot from the stands shows Febles talking to Kiner-Falefa at the base before Yamamoto is set. This is a screen shot as Yamamoto delivers the first pitch of the at-bat:

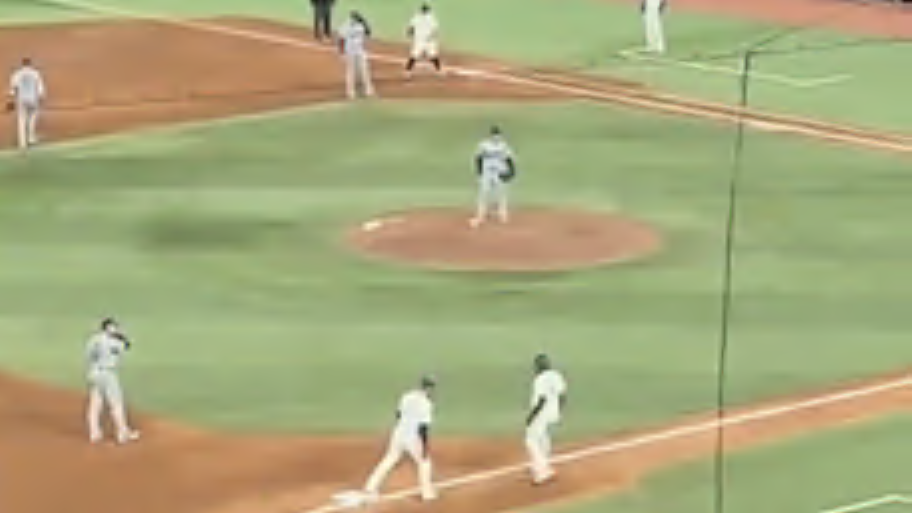

Before the next pitch, Febles walks to the baseline and appears to use his foot to draw a line in the dirt for a reference point:

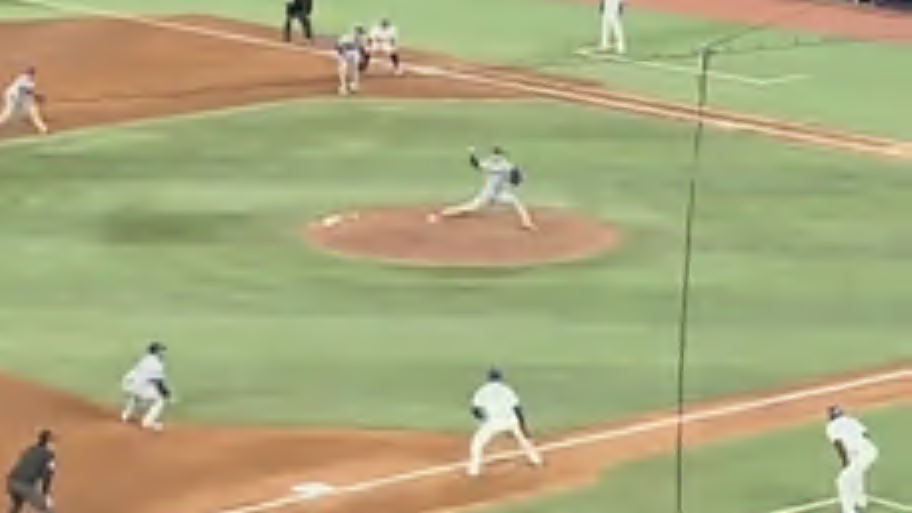

On the last pitch to Varsho, Kiner-Falefa is locked into that same short lead he had on the first pitch, right to the mark Febles made. (Take note in the screenshots of the “leads” at first base by Alejandro Kirk. No danger of him getting doubled up!)

b. His secondary lead was fine.

Again, bases loaded and one out—not two—calls for proper caution. You do not take an aggressive secondary lead where you create hard momentum carrying your body weight forward as the ball is hit. That’s when you see the slapstick stumbles and falls in a panicked change of direction upon seeing a line drive at an infielder. With less than two outs you must be under control enough to move quickly in either direction. Blaming Kiner-Falefa for not charging down the line with a hard secondary lead is unfair.

c. His slide was fine.

Is running through the base faster than a slide? Sure. But I’ve got to see a long highlight reel of runners standing up on a force play at home with less than two outs before I take this criticism seriously. It’s just not done. I don’t ever remember seeing it. Maybe it should be done, but it’s not common practice, especially when the runner also has the responsibility of breaking up a potential double play. Kiner-Falefa is using years of baseball instinct and observation to slide.

Here’s the bottom line: one executive timed out the play from contact off the bat to the catch by Smith. He clocked it at 3.5 seconds. For reference, a team typically needs to get the ball to second base on a steal attempt within 3.3 seconds to catch the runner after a normal lead of 11 feet or so. A stagger by Rojas upon setting his feet delayed the play a beat. At 3.5 seconds, Kiner-Falefa should have been safe.

Said one manager watching at home, “All 30 teams will be showing that play next spring training to remind players little things matter. He over-corrected. It’s the difference between the Jays winning the World Series or not.”

5. A crackdown may be coming on pitch-tipping ploys

Notice in the screen shots above that both coaches were in the confines of the coaches’ box. It happened all night in Game 7, at least when I first noticed after the third inning when crew chief Mark Wegner walked from second base to the Dodgers’ dugout to remind Roberts that coaches must remain in their respective boxes while the ball is live. That is a major departure from protocol, in which coaches routinely wander far out of the box.

MLB does have a rule, Rule 5.03, that requires coaches to remain in the box except to signal a player to slide, advance or return to a base. It is almost never enforced. Indeed, the rule stipulates “the umpire shall, upon complaint by the opposing manager, strictly enforce the rule.” One manager estimated when a team picks up tells from the opponent on what pitch is being thrown—by the setup of the catcher or the grip or quirk of the pitcher—the base coaches decipher and relay them “about 90 percent of the time.”

The base coaches in Game 7 were in rare obedient form. When one foul line drive whistled past Dodgers first base coach Chris Woodward, who normally would be standing past first base for self-preservation, the coach turned to first base umpire Adrian Johnson with a wry smile as if to say, “See?”

According to sources familiar with the routine pre-series meetings this postseason between MLB staff, umpires, managers and club officials, MLB vice president of field operations Michael Hill told managers Rule 5.03 would be more vigorously enforced this postseason. The dark art of “stealing” pitches by peering into gloves or deciphering tells, especially from foul territory, generated controversy this year that MLB wanted to avoid in the postseason. The rule, however, was enforced sporadically, if at all—until Game 7 of the World Series.

Before Game 7, Hill and the umpires again warned both teams the rule would be vigorously enforced. The penalty for a violation is the ejection of the offending coach. Nobody wanted sign-stealing shenanigans or an ejection in Game 7, so Hill and the umpires were proactive about avoiding any mess. Wegner reinforced the message early in the game.

I never understood why the rule has not been enforced. Let the players play and the coaches coach. All shenanigans from outside fair territory should be curtailed, especially when a rule already is in place. Keep the coaches in the box at all times, not just Game 7.

6. Be ready

Dodgers outfielder Andy Pages was benched amid a 4-for-50 slump. He was watching the game in a hoodie on the steps at the far end of the dugout when, in the bottom of the ninth with the bases loaded, bench coach Danny Lehmann ran from the home plate side of the dugout to tell him to go into the game in center field. The Dodgers wanted his better arm to replace Tommy Edman in a sacrifice fly situation.

Pages had been sitting for three and a half hours. He ripped off his hoodie and went searching for his glove. He found it on the bench and jogged out to center. Five pitches later—the next pitch after Rojas threw out Kiner-Falefa—Pages made what is probably the greatest catch in World Series history.

Yamamoto threw a first-pitch, nasty curveball that Ernie Clement somehow hit off his shoetops 366 feet—the second-longest ball hit off Yamamoto’s curveball all year. It would have been a home run at Fenway Park or Wrigley Field. It sailed directly over the head of left fielder Kiké Hernández, who was playing shallow.

Hernández sprinted back. The flight of the ball carried so directly over his head he arched his back and, mouth agape, began to reach with his glove running face first toward the wall. He was in a most difficult position for a catch.

Suddenly, superhero style, Pages arrived at the scene. Pages may have the better arm over Edman, but he is not as fast. His average sprint speed (28.1 feet per second) is a tick behind Edman’s (28.4). It is in the 69th percentile.

But on this play, Pages, who also was playing shallow, ran 29.2 feet per second—suddenly becoming faster than the average sprint speed of anybody on the team and in the 93rd percentile in MLB. He covered 121 feet, an amazing amount of area, while the ball was in the air for six seconds.

If the ball lands, the Blue Jays win the World Series and Clement is the MVP.

Pages caught the ball while leaping over Hernández. In a balletic pas de deux, the two outfielders were so intertwined that the ball went into Pages’s open glove as his right hand was in Hernández’s open glove.

Willie Mays made the most famous catch in World Series history. In the 1954 World Series he caught a 421-foot flyball from Vic Wertz with his back to the infield in a tie game with a runner on second base in the eighth inning. But that was Game 1—of a series the Giants won in a sweep.

This was Game 7. The series was over if Pages did not catch the ball.

7. Home runs win (cont’d)

Toronto out-hit and outplayed Los Angeles but lost because of the big fly.

Kiner-Falefa told me during the World Series the Blue Jays’ goal was to change baseball—to prove that playing old-school unselfish, put-the-ball-in play baseball can still win championships. Toronto played well enough to get within two outs of the title and prove that it can happen—it just didn’t happen because of the darn home run ball.

Here are the biggest hits of the World Series, according to championship Win Probability Added:

Five of the nine biggest hits were home runs by the Dodgers in the seventh inning or later. Teams went 25–3 this postseason when they hit a second home run and 22–44 when they didn’t.

The Dodgers hit .203, the worst batting average to win the World Series in the DH era (since 1966). They struck out a World Series-record 72 times. And yet they won because of five swings of the bat in Games 3 and 7.

Starting from 2020, here are the regular season home run ranks by the World Series winner: 1, 3, 4, 3, 3, 2.

8. Umpires are really good

Alan Porter, who may be the best ball-strike umpire in the business, missed only four called pitches in Game 5. Mark Wegner missed only 12 calls out of 291 pitches in the 18-inning, 6.5-hour marathon in Game 3. The crew immediately was on the dead ball call on the lodged ball in Game 6. Jordan Baker got the call right on the Kiner-Falefa slide at home.

Umpires are not perfect, and you can nitpick all you want about a call here and there, but the umpires got the big calls right so often that thankfully there was almost no talk about how badly we need ABS, the challenge system that is coming next season. MLB’s internal data showed that this was the highest rated World Series crew ever assembled as far as regular-season grades. It showed.

More MLB on Sports Illustrated

This article was originally published on www.si.com as Eight Lessons Learned From an All-Time Great 2025 World Series.