When Hideo Nomo joined the Los Angeles Dodgers, the public enthusiasm for the pitcher “was like a wave, and it just kept getting bigger and bigger,” Barry Stockhamer recalls.

Stockhamer worked for the Dodgers for 30 years, and when Nomo arrived from Japan in 1995, he was the club’s vice president of marketing. To describe the ensuing crush of media coverage, sponsorship requests and international engagement, Stockhamer has just the comparison.

“It was like a comet,” he says. “Except a tornado.”

That’s a reference to Nomo’s signature whirling delivery, of course, but it’s also a statement about the sudden, extraordinary opportunities he brought with him. Nomo was the first major Japanese star to make the jump to MLB. (Though he was not the first Japanese player to appear in the league: Masanori Murakami played two seasons for the San Francisco Giants in the 1960s before finishing his career in Japan.) Nomo’s decision to join the Dodgers meant the club gained a talented player on the field. It also gained a valuable conduit to Japanese and Japanese American fans that paid dividends for years to come.

Fast-forward to present day, and the Dodgers’ offseason thus far has seen them commit more than a billion dollars to a pair of Japanese superstars: reigning American League MVP Shohei Ohtani, making the jump in free agency after six years with the Los Angeles Angels, and 25-year-old pitcher Yoshinobu Yamamoto, coming to MLB after dominating in Japan’s NPB. These were the two best players available this winter in free agency—two generational talents—and that reality is reflected in their eye-popping, record-breaking deals. (Ohtani’s contract is the biggest in team sports; Yamamoto’s is the biggest for a pitcher in MLB.) Industry experts have noted the Dodgers’ investments here should come with plenty of opportunities for the team to benefit off the field. There are notable commercial possibilities and ways to engage new fans as the club becomes the de facto MLB team of Japan. And there’s an illustrative example in the Dodgers’ experience with Nomo almost 30 years ago.

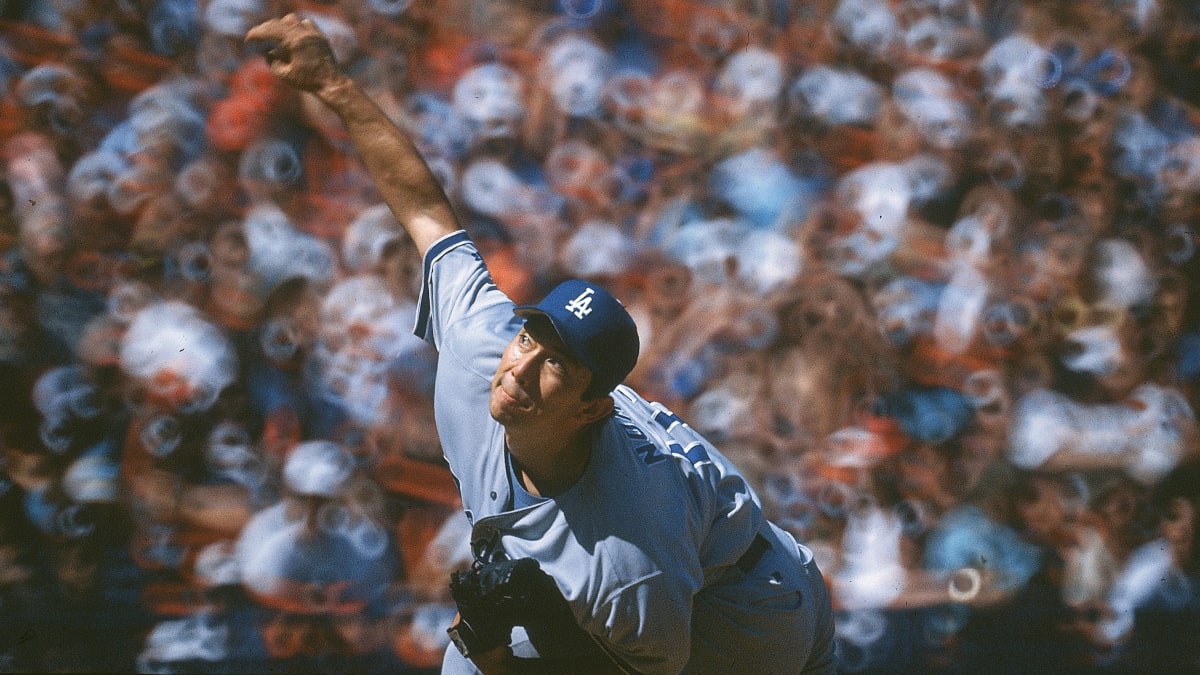

Heinz Kluetmeier/Sports Illustrated

Teams are constrained in how they can profit directly from the commercial popularity of individual players. International broadcasting rights are handled by MLB, as is the revenue from merchandise sold outside the stadium. But there are still plenty of avenues for teams to benefit through sponsorships, ballpark tours, attendance boosts and more. Which is just what the Dodgers saw with Nomo in the 1990s.

“His story captured the attention of an entire nation,” Stockhamer recalls. “From Day 1, there was a big media crush, lots of requests from international media. … It was an explosion.”

Japanese rice bowl company Yoshinoya opened a concession stand at the stadium. There were travel package tours from Japan to L.A. built around Nomo’s pitching schedule. The Dodgers began selling Nomo merchandise at the ballpark with a special tag reading “only from Dodger Stadium”—differentiating it from anything that could be purchased anywhere else—and saw people flock to the park just for those items. Stockhamer recalls a group of Japanese businesspeople once coming on a ballpark tour, spending tens of thousands of dollars on Nomo merchandise and saying they were getting right back on a plane to Tokyo.

Much of that interest arose naturally as it might with any talented player; Nomo was selected to start the All-Star Game in 1995 and went on to win National League Rookie of the Year honors. But the Dodgers also used his presence to engage new fans who might not have paid attention to MLB otherwise.

Shortly after Nomo signed with the Dodgers, the team met with the publishers of newspaper Rafu Shimpo, the largest bilingual English-Japanese paper in the U.S., to discuss coverage and ensure there were opportunities for stories in both languages. The Dodgers printed a newsletter and pocket schedules in Japanese and distributed them around L.A. “to make sure we were reaching people who weren’t necessarily baseball fans,” Stockhamer says. They reached out to local Japanese schools and religious centers to schedule group outings and experimented with sharing Nomo interviews on their fledgling website. “It was pretty hard to get your arms around all the exposure that you got,” Stockhamer says, and the team saw an attendance boost to match.

“There were some nights you knew he was putting 10,000 people in the park,” Stockhamer says.

The Dodgers were in many ways uniquely positioned to tap into this fanbase. Los Angeles has long had a robust Japanese American community. Former Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley took a serious interest in Japanese baseball and had the Dodgers make MLB’s first goodwill tour to Japan in 1956—playing 20 games across the country that November. (In fact, Jackie Robinson’s last games in a Dodgers uniform came on that trip to Japan.) The following year, O’Malley invited the Tokyo Giants’ manager and several players to come to Dodgers spring training at Vero Beach. “This is our way of returning the many goodwill gestures of our recent hosts,” O’Malley told newspapers. “We feel that this exchange of ideas will aid the development of the game of baseball in a country where interest in baseball is truly amazing.” The Dodgers went on another such tour in ’66 and had Vin Scully narrate a television special about the journey. And when O’Malley’s son Peter assumed control of the team a few years later, he tried to continue his father’s work in maintaining those connections to Japan.

“After I met Peter O’Malley, I wanted to play for the Los Angeles Dodgers,” Nomo said through an interpreter in his introductory press conference. “The Giants and the Mariners did not have a Peter O’Malley.”

The Dodgers’ ownership has changed hands several times since O’Malley sold his family’s stake in 1998. But the legacy resonates still. “It was opening these international doors which mean so much to baseball,” Stockhamer says. “That goes beyond just one player. It’s the cordial relationship and nurturing of the sport internationally.” It’s hard to place a specific dollar amount on that. But in Stockhamer’s estimation, it’s more than paid off.

“I couldn’t quantify it,” he says. “But you had tangibles and intangibles, like cultural impact, like connecting with young people who became Dodger fans and guess what? You were on the road to creating lifelong fans there. … You have viewership, merchandising, ticket buying, all these things, but there was also the long-term impact of just that goodwill.”