TORONTO — Dodgers infielder Miguel Rojas was leaving the team hotel Saturday for World Series Game 7 when his wife, Mariana, left him with a kiss and a message: “You’re going to hit a home run today.”

Rojas chuckled. Mariana had told him the same thing yesterday. Actually, she had done so almost every day since the Dodgers clinched the National League pennant after he let slip to her, “I want to hit a home run in the World Series.”

Rojas did not have a hit in 31 days, partly because he went 25 days without starting, a period in which he would respond to Mariana’s message by saying, “How am I going to do that? I’m not playing.”

This day, Mariana insisted, was different. Mariana told him she had prayed on it and received a vision from God of the number 11, the number Miguel wore as a child in Venezuela and then adopted in 2022 with the Marlins to honor his grandfather and mother, who passed away within the same week that January. He kept No. 11 with the Dodgers until yielding it to rookie pitcher Roki Sasaki this year.

“I am 100% sure you’re going to hit a home run in this game,” she said. “You have to believe it. You have to trust in God that this is going to happen for us.”

“I trust you,” he said.

Around the same time, about 2 p.m., Yoshinobu Yamamoto arrived at the Dodgers clubhouse. Yamamoto had thrown 96 pitches the previous night over six innings to win Game 6, 3–1, over the Toronto Blue Jays. Word reached pitching coach Mark Prior that after the game Yamamoto retired to the training room to have physical therapists work on getting his body to recover. He was thinking about Game 7 as soon as Game 6 ended.

“He got to work [Friday] night and it was all about getting his body ready,” Prior said. “You know, he didn't celebrate.”

Yamamoto went to the outfield after his arrival Saturday. He went through a flat-ground throwing session and long toss to see how his arm felt as Prior watched. When he was done, Yamamoto told Prior he was ready when needed.

“I don’t know how much I’ve got,” he told Prior through his interpreter, Yoshihiro Sonoda, “but I can give you something. All I need is to be given enough time to warm up.”

Prior swelled with admiration.

“Most guys,” he said, “can’t lift their arms the next day.”

Championships are towers of achievement that last all eternity. The Los Angeles Dodgers built one of majestic height, becoming the first team in 25 years to repeat as World Series champions. It took them 73 grueling innings to put away the persistent Blue Jays, the most ever over a seven-game series.

Like a captivating novel, the series unfolded in twists and turns so wickedly good you didn’t want it to end. And at times it looked like it wouldn’t. It was deadlocked three games each and Game 7 squared at four each after 10 innings. Dodgers catcher Will Smith delivered the ultimate highlight shot: an 11th-inning home run off a 2–0 hanging slider from Shane Bieber that decided the championship and provided the final 5–4 score. It was the first extra-inning home run in World Series Game 7 history.

True to his homespun, aw-shucks demeanor and Huck Finn nature, Smith said, “I was only trying to get on base for Freddie [Freeman].”

The source of the championship, like a tower’s foundation, remained mostly unseen. Below the $350 million payroll, the four MVPs, the $1.3 billion worth of pitching they threw at Toronto in Game 7, the not one but two charter planes they own, the talk of a new dynasty (it’s real: from 2020–25, three titles and 56 wins ahead of the field) and all the home runs they hit (the Dodgers are the fifth straight World Series champion to rank in the top four in MLB in home runs) is something as subtle as a look in the eye.

It is the look Yamamoto gave manager Dave Roberts in the 17th inning of the Game 3 epic, two days after the 5-foot-10 righthander became the smallest pitcher in 62 years to throw a World Series complete game (Billy Pierce of the 1963 Giants). After Prior told Roberts that Yamamoto volunteered to pitch, Roberts glanced over his shoulder down the dugout, saw the earnestness on Yamamoto’s face and could not refuse him and told him to go warm up.

Rojas would have been Roberts’s choice as his next pitcher if Freeman had not ended the game with a walkoff homer in the 18th.

“I’m not going to let us lose a World Series game,” Yamamoto told Prior, “with a position player pitching.”

It was the same anything-it-takes look Yamamoto gave before Game 7.

In the same trustworthy way, after the Dodgers lost Game 5 in a dull 6–1 loss to rookie sensation Trey Yesavage, Roberts, in the text version of a look in the eye, texted Rojas, “You’re playing Game 6.”

Rojas texted back, “I’ve got you, Doc.”

Rojas had not started a game since NLDS Game 2.

APSTEIN: The Dodgers Aren’t Ruining Baseball—They’re Just Doing Everything Right

The move with the team’s season on the line had nothing to do with analytics or matchups. Explained Roberts, “I just decided there was no way I would allow us to lose the series without using Miggy Ro. He’s been a great teammate and glue guy for us all year. He deserved to be in there for everything he has meant to us.”

The Smith home run is the money shot of the series. The belief in Yamamoto and Rojas in the blink moments of competition is where Roberts defined the foundation of the Dodgers’ success.

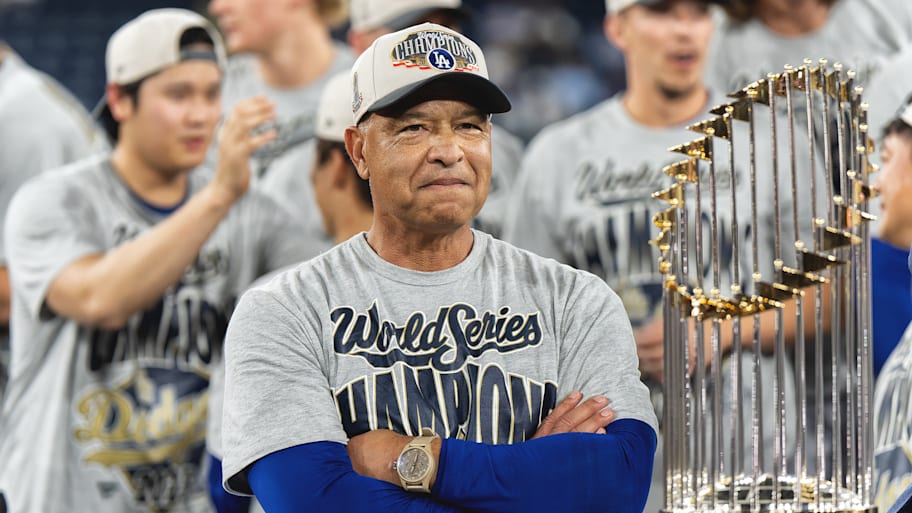

“I’ve learned after winning three,” Roberts said, “that you’ve got to use your eyes, you’ve got to use your gut and you’ve got to trust your players. And I have enough players that I trust. I have all that other stuff. But you’ve got to let players play. They want to compete. And I hope now people understand that I don’t just look at numbers.”

It was the bottom of the ninth inning. The Dodgers were two outs from losing Game 7, 4–3. The Dodgers, and Mariana, were running out of chances.

A three-run homer by Bo Bichette, playing on one good knee, would go down in Blue Jays history in the Mount Rushmore of franchise home runs, along with Joe Carter in 1993, José Bautista in 2015 and George Springer in 2025 ALCS Game 7. Four homers of the same suit: three-run shots by right-handed sluggers into the left field seats of Rogers Centre, né Skydome. Closer Jeff Hoffman had only Rojas and Shohei Ohtani between him and the franchise’s first title in 32 years.

On the sixth pitch of the at-bat against Rojas, Hoffman threw a sloppy slider up and in to run the count full.

Mariana looked at the digital clock in right-center field. She nearly gasped. The red numbers glowed “11:11.”

“Our number,” she said.

Hoffman knew he needed to throw a strike. Walking Rojas, the number nine hitter, would bring Ohtani to the plate as the potential go-ahead run.

Needing to throw a strike, Hoffman chose a slider, a poor choice when its path must be in the strike zone the entire flight. Then again, Rojas wasn’t much of a power threat, especially against breaking pitches from righthanders. He had seen 3,695 of them in his career and hit only three home runs. Three out of 3,695.

History changed with right-handed breaking pitch No. 3,696. Rojas hit it farther (387 feet) and harder (104.9 mph) for a home run than he did any of the other ones. It was the swing of his life. As he crossed the plate he pointed toward Mariana in the stands.

“But I was screaming and crying,” she said, “so I really didn’t know. ... It was like I felt God is telling me, ‘I told you it's going to happen, and you have to have your faith in me no matter what happened.’ Because it looked like everything was lost. It’s amazing. God is amazing.”

The at-bat only happened because Roberts wanted to reward his glue guy and give him a chance.

“He told me, ‘Finally I have my chance,’” Mariana said. “He was excited. But he wants to do the best for the team. It’s not just him. It’s all the players here. They are teammates. They are not looking to be the best. They are so humble and that’s why he fits in here. So, it's great for him, but he didn't care as much as he can help the team.”

Roberts’s hunches seemed to be rewarded at every turn. Smith homered from the No. 2 spot, where Roberts put him in Game 5 to protect Ohtani, who kept drawing walks. Mookie Betts, the erstwhile No. 2 hitter, was dropped to fourth for Game 6, his lowest spot in eight years, and promptly smashed a two-strike, two-run, two-out dagger of a single that turned Game 6.

The homers by Rojas and Smith rank among the five most clutch home runs in World Series Game 7 history, as ranked by win probability added. No. 1 is the 8th-inning, three-run shot by Hal Smith of Pittsburgh in 1960, followed by Will Smith’s home run, the Rajai Davis home run in 2016, the Bill Mazeroski series-winning homer in 1960 and Rojas’s home run.

The Dodgers out-homered the Blue Jays, 3–1, in Game 7, winning the argument of whether contact hitting like Toronto showcased could outflank a home-run based offense. Teams that hit a second home run this postseason were 25–3. Teams with one or no home runs were 22–44. The Dodgers hit just .209 in the World Series but out-homered the Jays, 11–8.

Roberts brought Yamamoto into a firestorm in the bottom of the ninth. Two runners on and one out. Yamamoto hit the first batter he faced, Alejandro Kirk, to load the bases. Roberts brought the infield in. Daulton Varsho bounced a hard grounder to Rojas, who stumbled on the turf, righted himself and threw home to Smith, who barely dropped his spike on the plate in time for the force out.

Then, another scare: a long fly ball from Ernie Clement over the head of left fielder Kiké Hernández that seemed headed for the wall as a series-winning hit. Suddenly, flying above Hernández, center fielder Andy Pages made a game-saving catch. Roberts had inserted Pages into the game for defense only two batters earlier.

APSTEIN: Blue Jays’ Many Missed Chances Leave Behind a Heartbroken Team

Yamamoto pitched a 1-2-3 10th inning. How long could he go?

“He came in the dugout and said, ‘Daijoubu’—I’m good,” Roberts said. “We were going to live and die with them.”

After Smith’s home run, Yamamoto went back out for the 11th. Prior turned to Roberts and took a moment to marvel at what they were watching.

“Nobody does this,” Prior said.

He added later, “It’s just not something that's done, especially now, but it's not ever done a lot in the past. So, we didn't know where we were with him. Clearly, we could see that his stuff was good. But we're still getting one of the best offensive teams that we've run across in years.”

It would take more maneuvering for Yamamoto to escape one last time. He survived a leadoff double by Vlad Guerrero Jr., who was bunted to third base, by pitching around Addison Barger with a four-pitch walk and getting a ground ball double play from Kirk.

Back in 1926, Grover Cleveland Alexander won World Series Game 6 for the Cardinals and saved Game 7 the next day. Randy Johnson won Game 6 for the Diamondbacks in 2001 and Game 7 the next day. Yamamoto joined them in World Series tireless excellence in crunch time. Said Prior, “He’s been in his zone for this last month. And we’re just kind of the beneficiaries of being able to watch as fans, as coaches, as people who support him. It’s pretty special. He cares about winning.

“He’s an ultimate team guy. It’s all about winning games at this time of year. You see how everybody rallies around him, what he does and how he takes care of himself and prepares. He’s prepared for this moment over a lot of years.

“Emotional, yeah. I mean, it’s unbelievable. It really is. That’s going to go down as one of the best championship performances in any sport. Warming up in the 18th? And this? Absolutely. Well-deserved MVP.”

Hours before what would be the longest World Series Game 7 in 101 years, in which Roberts would use all four of his starting pitchers (Ohtani, Tyler Glasnow, Blake Snell and Yamamoto) and have another warming in the bullpen (Clayton Kershaw), the manager sat in his small office at Rogers Centre with his lineup card in his hand and multiple contingencies in his head. He was asking too much, as it turned out, from a worn Ohtani, pitching on short rest in a year in which he played in 175 games and took 810 plate appearances.

“I don’t know how he’s going to attack,” Roberts said. “It’s a great question. But he has such good feel out there. We’ll see.”

Ohtani couldn’t make it through three innings. The game grew as twisted as a boxed set of Christmas lights, as the whole series seemed to be. The Blue Jays led 3–0 and 4–3. The Dodgers never had a lead until the Smith homer in the 11th. Thirteen pitchers were summoned. It was four hours and seven minutes of G-forces. But even before all that played out, Roberts in his office thought about how he would want his team to be remembered.

“This thing started in the beginning of February,” he said. “Early spring training, all the way to Tokyo, all that we had to endure and then have to turn into November, and this team remained together and focused.

“This is what a manager dreams of a ballclub. It really is. These guys had the same true passion and perseverance toward a long-term goal.”

It would be half-past midnight when Roberts stood in center field, confetti all around him, and the glow of victory lasting proof of that perseverance. He was thinking about Yamamoto, the symbol of that perseverance, when he said, “We’ll never see anything like this again.” His words just as well fit how the Dodgers won the World Series.

More World Series on Sports Illustrated

This article was originally published on www.si.com as Dodgers Become Baseball’s Modern Dynasty With an Unforgettable World Series Win.