In the series premiere of Desus & Mero, the co-hosts, Daniel “Desus Nice” Baker and Joel “The Kid Mero” Martinez, enter a New York City classroom ready to be clowned. “Late night for the people!” Desus announces to a room of unimpressed elementary schoolers. The children immediately fire off both questions and roasts: “Do you have kids?” “What did you do before TV?” “Aren’t you the guys who got dragged by DJ Envy on The Breakfast Club?” The skit ends with one girl saying, “You guys seem a little too ghetto to be on TV.”

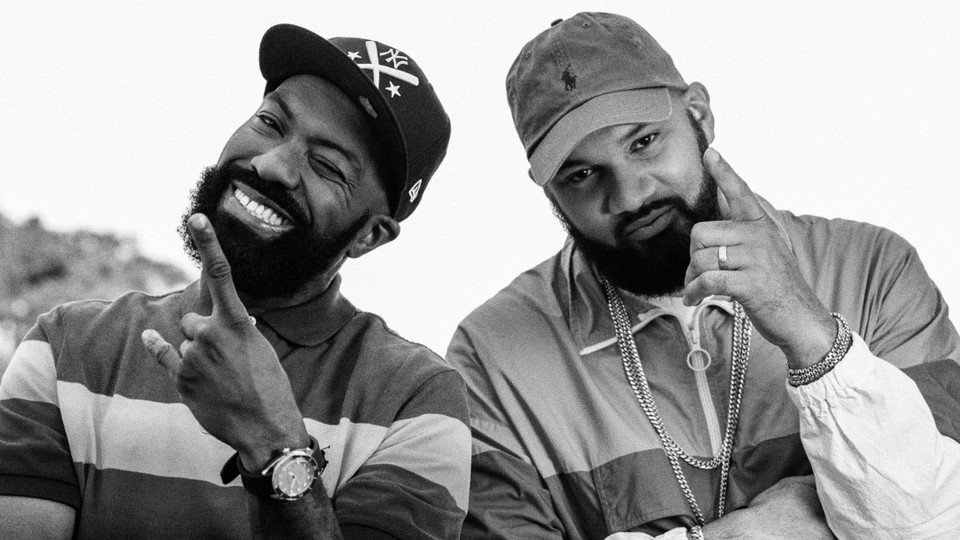

The (scripted, I’m sure) comment noted the obvious: Neither Desus nor Mero looked, sounded, or behaved like other mainstream late-night hosts, many of whom are wealthy white men in suits. Desus and Mero—of Jamaican and Dominican descent, respectively—had heavy New York accents, wore casual attire, and cursed openly and often. But more important, they openly embraced their connection to a version of the city that the elementary-school classroom represented: a New York populated primarily by working-class families and immigrants, where more than two-thirds of inhabitants are people of color, mostly Black or Latino.

When Desus and Mero’s show debuted on Showtime in 2019, the Bronx-bred duo seemed primed to launch a new era of late-night TV. By the Season 2 premiere a year later, David Letterman was calling them “the future” of the industry. The show continued a strong run, featuring guests as varied as Eddie Murphy, Sandra Bullock, and Chris Smalls, who organized the Amazon labor union on Staten Island. But then, last month, Showtime announced that the series wouldn’t return for a fifth season. The hosts were ending their creative partnership, including, to the heartbreak of thousands of viewers and listeners, their popular, long-running podcast, Bodega Boys.

The reason for the show’s cancellation is unclear. In a recent interview, Mero said that he and Desus had been discussing the split for more than a year. Yet in June’s Season 4 finale, Mero said that the show would only be taking a summer break, and shortly before Showtime’s announcement, fans were speculating about tension between the duo. Whatever the exact cause, the end of Desus & Mero is a loss not only for their fan base—nicknamed the Bodega Hive—but also for the broader television landscape. The show spoke to New Yorkers who grew up or live in the hood, provided a space for Black celebrities to show up as their full selves, and created a space where Black men in particular could tune in to conversations that sounded like ones they might have with friends.

[Read: 20 perfect TV shows for short attention spans]

The Desus & Mero set, a departure from typical late-night studios, captured the show’s ethos. The co-hosts sat side-by-side on a low stage, with no desk separating them from the audience or their guests. The interviews were held first at a table crowded with graffiti (drawn by Mero) and most recently on a set modeled after a bodega, stocked with candy, beer, Jesus candles, toilet paper, and a sneaker display. Most of the props bore either the Desus & Mero logo or one of their catchphrases. (The brand was, as they always said, strong.) The flags of both of their islands were ever present, as were liquor bottles made to mimic Brugal, a Dominican rum. Desus and Mero wore Timbs, puffer jackets, and fitted caps—a uniform familiar to Bronx natives and many of the city’s Black and Latino residents. Mero in particular often repped Dominican paraphernalia, whether an Águilas sweatshirt (for one of the country’s baseball teams) or attire from local Latino-owned brands.

The duo’s path to fame didn’t resemble the one taken by many other late-night hosts: Go to a prestigious improv school, get hired at Saturday Night Live, and then wait your turn for a solo break. Desus had been a strip-club manager, a mechanic, and a bartender before working in media; Mero held jobs in IT and as a special-education paraprofessional. Their backgrounds featured prominently on the show and allowed them to wade into comedic territory that other late-night hosts wouldn’t or simply couldn’t touch.

Take, for instance, Desus’s mocking defense of the basketball player Tristan Thompson, which referenced the stereotype that Caribbean men cheat on their partners. “You know about us Jamaicans. We’re loyal,” he said in one episode. And then, after a pause: “to all our families.” They made frequent mention of Dominicans bringing spaghetti to the beach (if you know, you know) and of the regular fights that break out in City Island restaurants. Sometimes, the co-hosts bantered about drug addiction in Black neighborhoods, stop-and-frisk, and their parents’ threats to send them back to the islands when they disobeyed them. Though ostensibly dark, these moments reflected the humor that people who face these daily indignities use to cope. The cultural specificity kept them close to their New York City roots and their goal of creating a late-night show “for the people.”

Late-night shows also depend on celebrity access and memorable conversations, and Desus & Mero gave Black stars a space in late night where they didn’t have to code switch. In a Season 1 interview with the Black Panther actors Winston Duke and Lupita Nyong’o, the hosts pulled up a picture of Duke wearing leather slides—the “official footwear of every African or West Indian father,” Desus observed. Duke had been called out by his Instagram followers for wearing the open-toed sandals while doing construction work around the house. “And then you see all the Caribbeans coming on like, ‘What’s the problem?’” Duke recalled. “That’s regular footwear.” They talked about immigrant parents’ expectations, and Duke mimicked his family members’ accents. In the Season 4 premiere, the hosts spoke with Denzel Washington (who was promoting The Tragedy of Macbeth) about having an overprotective mom and growing up in Mount Vernon, close to the Bronx. Mero dubbed the actor “Hollyhood.” (In contrast, Washington spent most of his appearance on another show quoting Shakespeare with the white host.) Desus and Mero also featured people who may not otherwise have been welcome in late night, including bodega owners; strippers; the rapper Bobby Shmurda, who was in prison for more than six years; and local internet celebrities such as the Long Islanders Bigtime Tommie and DJ Vinny Dice.

The pair didn’t have much regard for respectability politics or political correctness. The N-word was used regularly, as was the term crackheads to refer to people addicted to drugs. Desus and Mero’s refusal to self-censor was part of their appeal and a reflection of conversations you might hear on East Fordham Road in the Bronx or on Jamaica Avenue in Queens. Still, they could be quick to correct themselves if they said something uncouth. During a bit on a Pride Month tweet by the CIA, in which the agency posted a supportive message of its gay service members along with a photo of a combat helmet with rainbow-colored ammo, Desus made fun of the “gay bullets.” But he immediately stopped himself: “Why are we calling them gay bullets?” These moments showed the co-hosts’ openness to growth and respect for shifting public sentiment about social issues.

As the seasons went on, the pair’s stature grew. They became friends with celebrities, and their newfound fame appeared to fuel their disagreements over what was or wasn’t appropriate to say on air. Desus in particular seemed more concerned with maintaining professional relationships. (In a segment on Mariah Carey’s 2021 holiday campaign with McDonald’s, Desus cringed at Mero’s suggestion that the singer was wearing shapewear. “When we eventually interview her, she’s going to ask about that comment,” he said.) Although both maintained their irreverent, raunchy, off-the cuff humor, Mero seemed to stay away from the glossy world opening up to them as a result of the show—in large part because he was a family man with four children—and Desus would often side-eye or distance himself from Mero’s potentially offensive comments. “Hollywood Desus” became a running joke between them and the Bodega Hive, although these jokes seemed less lighthearted by Season 4. At times, this tension made the show less fun to watch.

But no matter the growing pains, that Desus and Mero made it to television at all was a seismic achievement. Since the series premiered in 2019, other shows filling a similar void have cropped up. In HBO’s Pause With Sam Jay, for instance, the comedian Sam Jay gathers friends—including formerly incarcerated people, government workers, and fellow entertainers—for broad-ranging conversations about issues such as capitalism, conspiracy theories, and LGBTQ education in schools. But no series offers the authenticity and local New York City perspective of Desus & Mero. The show’s loss means one less space for people who grew up in the hood to feel seen and welcome and, most important, not judged—as Desus always said, “God’s working on all of us.”