“Now I have to worry about where to live,” said Sulekha Paswan, a 45-year-old domestic worker in Delhi. “And food for my children.”

Sulekha has been staying in a relative’s house in a South Delhi slum after her home was demolished in Bhoomiheen Camp in Kalkaji earlier this month. She had received her eviction notice just three days before it took place. Sulekha watched bulldozers flatten her home and her neighbourhood – a clear violation of Supreme Court guidelines, which mandate that residents like her must be given at least 15 days’ notice.

Since the BJP came to power, Newslaundry has assessed that over 27,000 people have been displaced by demolition drives across Delhi. At least 9,000 have been denied rehabilitation under public housing rules, leaving the city’s working poor stranded. Sulekha is one of them.

In 2023 alone, Delhi accounted for 2.8 lakh of India’s five lakh forced evictions – the highest in seven years. Between hurried court orders, narrow cut-off dates and patchy surveys, thousands of families face eviction, inadequate resettlement, or none at all. Promised housing, when it comes, is often unfit to live in. As one urban planner told Newslaundry, Delhi’s urban renewal is still “planning as a weapon.”

In the last four months alone, the city witnessed demolition drives at eight major sites. Bulldozers moved across affluent Sainik Farms in South Delhi to Old Usmanpur village on the Yamuna floodplain in the North-east, and from Ashok Vihar and Wazirpur in the North-west to four drives in Bhoomiheen, Madrasi, and Taimoor Nagar camps in South-east Delhi.

Newslaundry looked into these demolitions, their impact, and the people affected by them.

Contradictory numbers

Rehabilitation remains a mammoth task in a country where the right to housing has not been recognised as a fundamental right. In Delhi, all the rehabilitations are overseen by the Delhi Urban Shelter Improvement Board.

According to the 2011 Census, approximately 10.8 percent of Delhi’s population resides in slums (data on Dataful here). Yet estimates of the number of people vary wildly.

The Delhi government’s own survey in 2010 puts this number at 5.8 lakh families living in 4,390 slums. The DUSIB website, on its part, says that approximately 30 lakh people, or six lakh families, live in urban slums.

The 2006 Delhi Human Development Report states that 45 percent of the city’s population – then estimated at 140 lakh people – live in slums, including informal settlements like squatter colonies, illegal sub-divisions and unauthorised developments. And Asha India, an NGO, estimates that Delhi has “about 750 big and small slums” that are home to 3.5 lakh families, or approximately 20 lakh people.

These contradictory numbers make a bad situation worse. “There is no clear record of slum dwellers in the city,” said R Srinivas, a former town and country planner with the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs. “Only when there’s one, can planned relocation of the slum dwellers be possible.”

Compounding the issue is the question of whether there’s enough space for relocation in Delhi.

“A city like Delhi where land is already scarce, the displacement to relocation gap will exist,” Srinivas said. He suggested that some of the displaced people can be relocated into the “periphery areas in the NCR region, but then the authorities must come with a plan for rehabilitation for the entire NCR region”. With the number of slum dwellers so high, it will be “virtually impossible to rehabilitate everyone”.

The policy to guide rehabilitation of slum-dwellers is the Delhi Slum & Jhuggi-Jhopri Rehabilitation and Relocation Policy 2015, approved by the Delhi Cabinet in 2016.

Under the policy, the AAP government had initially approved February 14, 2015 – the day it assumed office in Delhi – as the cut-off date to grant protection to jhuggis from demolition. This date was later revised to January 1, 2015, following a directive from the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs.

The policy also says that JJ clusters established before January 1, 2006 – about 675 JJ clusters, of which about 348 are controlled by the Delhi Development Authority – will not be removed without proper rehabilitation. The clusters that don’t make it to this list fall into a bureaucratic void, leaving their residents with no legal protection and no rehabilitation.

Newslaundry sent a questionnaire to the DUSIB. This report will be updated if they respond.

Recent demolitions

Newslaundry analysed the numbers behind a spate of demolitions in Delhi since March.

March 5: Yamuna floodplain area

On March 5, an anti-encroachment drive was carried out in the Yamuna floodplain area, impacting nearly 200 families in the area according to various media reports. The notices were reportedly served only three days prior to the demolition.

April 24: Sainik Farms

A demolition that did not displace people took place in Sainik Farms. On a humid evening between April 24 and 26, bulldozers broke into Sainik Farms, an unauthorised yet affluent colony in Delhi. Over three days, 1.25 acres of reported encroachments were cleared on orders from Delhi LG VK Saxena. This came just weeks after the Delhi High Court, in March, had reprimanded the Centre for failing to resolve the colony’s legal irregularities.

May 5: Taimoor Nagar Indira Camp

Following the Delhi High Court’s order in December 2024, the DDA razed 100 structures in Taimoor Nagar, along the local drain, displacing around 480 residents on May 5. The high court had declined to halt the demolition of encroachments along the drain, attributing flooding in parts of the capital after showers and thunderstorms to the drain’s inability to carry rainwater downstream because of these encroachments.

May 5: Wazirpur

Wazirpur in Northwest Delhi saw several demolition drives along the railway lines. The first drive took place on May 5 on the Wazirpur railway line in which 220 houses were razed and nearly 1,056 people were affected. These figures are gathered through an assessment report produced by Delhi Housing Rights Task Force, a collective of organisations and individuals working to safeguard human rights, adequate housing, and other allied rights, with a focus on the National Capital Region of Delhi.

June 1: Madrasi Camp

Another slum which saw demolition drive is Madrasi Camp which was demolished on June 1. The land owned by Railways saw of the 370 families counted by DUSIB, only 189 were granted rehabilitation. The remaining 182 households of about 900 people were cast into uncertainty. The eligible residents were given a home in Narela, at least 50 km away from their present residence. Newslaundry reported on the demolitions and their impact here and here.

June 2: Model Town, Wazirpur

On June 2, the Northern Railways demolished jhuggis on one side of a railway track in Model Town. The railways said the demolitions were necessary to restore visibility of railway signals and ensure operational safety. About 200 houses were razed and 960 people were displaced, as per the Delhi Housing Rights Task Force.

June 10: Wazirpur

On June 10, 100 houses were demolished in the Wazirpur industrial area, displacing at least 480 people.

June 11: Bhoomiheen Camp

On June 11, 344 homes equal to five acres of land in Bhoomiheen Camp were razed. A DDA survey of 2,891 families cleared 1,862 families to relocate, but left over 5,000 people out.

June 16: Ashok Vihar

On June 16, Ashok Vihar saw nearly 200 structures razed in the Jailorwala Bagh area. According to DDA records, 1,078 households have been rehabilitated in the Swabhiman Apartments nearby, while 567 households were declared ineligible, leaving roughly 2,800 people without rehabilitation.

Losing their homes

But what about the faces behind these numbers?

Most of those displaced from their homes are daily wage earners, construction labourers, auto-rickshaw drivers, and domestic workers like Sulekha Paswan, who lost her home in Bhoomiheen Camp.

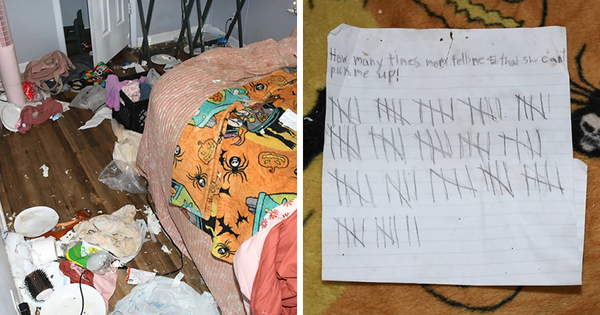

Bhoomiheen Camp figures on the DUSIB’s list of clusters whose residents qualify for rehabilitation, since it was established before January 1, 2006. Residents were given flats in a DDA housing complex in Kalkaji that had been inaugurated by Prime Minister Narendra Modi in 2022. But residents have complained about the poor condition of the complex.

And not everyone from Bhoomiheen Camp got a flat. Sulekha says that despite owning a ration card and living in her home for years, she was told by the DDA that she doesn’t qualify for rehabilitation because she lived on the first floor. It’s unclear why this is the case.

Similarly, Kamlesh, a resident of Bhoomiheen Camp who watched his house being demolished, was not allotted a home. Kamlesh, who is in his fifties and works in a tea stall in Chittaranjan Park, told Newslaundry: “I don’t have money to rent any accommodation. I sometimes sleep at the tea stall, other days on the footpath.”

Ashok Vihar’s rehabilitated residents were given houses in the Swabhiman Flats, which were inaugurated by Prime Minister Modi in January this year. Residents here too complain of poor living conditions. Rekha, one of the rehabilitated residents, told Newslaundry, “We face water issues, sometimes it comes late or scarcely. One toilet for my family of six is not convenient.”

Suman, a resident of Madrasi Camp who did not get rehabilitation in Narela, located 50 km away, is living in a rented room nearby in Sarai Kale Khan, where her family of four pays Rs 10,000 every month. “My husband and I have to manage somehow so that our kids are not taken out of school,” she says.

In Taimoor Nagar Camp, Lala Chauhan is one of 14 residents petitioning the Delhi High Court with the request to not demolish without “proper rehabilitation”. Their pleas were dismissed. He is currently living in Faridabad. “We keep returning to the rubble which was once our house,” he says.

Another resident of Taimoor Nagar whose house was demolished is currently living with his brother in Khadar. The resident, who did not want to be named, works as a sweeper in a private company.

“I am not married, I used to live there with my mother after she passed away,” he said of his lost home. “I was living alone but now I have to stay here with my brother and his family which is inconvenient since there are already five members in his family.”

It should be noted that AAP leader and former CM Atishi was “removed” by the Delhi police when she tried to visit residents of Bhoomiheen Camp shortly before the demolition. Senior AAP leader Saurabh Bharadwaj accused the BJP of breaking its promise to provide “housing for all” by 2022. Party president Arvind Kejriwal alleged that while the BJP “tried to demolish 48 slums” in five years, he “saved 37 of them”.

Rekha Gupta, the current CM of Delhi from the BJP, said the AAP was trying to “politicise” the issue and that demolitions had been carried out as per court orders. She also said no slum would be cleared without prior rehabilitation – even though this is far from true on the ground.

Srinivas said, “All of this is for vote banks. Because if any government will provide them with housing rights, they will definitely vote for them…The previous government might not have supported demolitions hence many might have supported them but the present regime is saying demolitions are being done on court orders. So this tussle continues.”

Courts and compliance

Many of the demolitions in Delhi seem to violate the Supreme Court’s guidelines to give residents a written notice 15 days in advance, or to permit homeowners to dismantle illegal structures themselves.

For example, residents in the Yamuna floodplains received a notice on March 2 for a demolition that took place on March 3. Bhoomiheen Camp got four days’ notice. Taimoor Nagar got nine days’ notice.

What role do courts play?

In August 2022, the Delhi High Court relied on the 2015 Slum Rehabilitation Policy to reject rehabilitation claims for Shakarpur Colony, arguing the cluster wasn’t on the protected list of 675 slums. Demolition drives in Madrasi Camp and Taimoor Nagar Camp were backed by high court orders for drain desilting.

In some cases, courts have provided relief. At Bhoomiheen Camp, out of 417 petitions, 180 appeals succeeded and secured rehabilitation. Nearly 250 households in Ashok Vihar avoided demolition thanks to stay orders. Yet even houses with active stay orders were razed.

The Kathputli Colony remains a cautionary tale of unfinished promises. Delhi’s first in-situ redevelopment plan began there in 2014, displacing about 4,000 families. Over 2,800 were shifted to a transit camp, promised improved housing in new towers. A decade later, these towers are still under construction.

Newslaundry asked advocate Pawan Reley on the role played by the judiciary in demolitions. He said, “The Delhi High Court has acted in accordance with the kind of litigations it was approached with related to how the government authorities are not functioning properly in case of drains. But the court is not going to the root cause of it. The relocation gap stays as the ineligible displaced residents will go to some place else when they are kicked out of their current ones. Providing rain bhasera is not the permanent solution.”

He warned that when displaced families rebuild on new land, they again face eviction because the cut-off date for rehabilitation remains frozen at 2015: “These people will again be rendered homeless, so this relocation gap will always exist.”

Past rulings reflect this. The Supreme Court in 2020 ordered the removal of 48,000 jhuggis along railway tracks. The DDA says that out of 378 slum clusters under its purview, only 205 have been surveyed so far – with the rest in limbo. Delhi’s Master Plan 2021 proposes relocating slum clusters on plots smaller than 2,000 sqm, putting nearly 70,000 people at risk if families average five members each.

“We have neither effective citywide coordination nor empowered local planning,” said Hitesh Vaidya, former director of the National Institute of Urban Affairs. “What’s missing is a layer of city planning that listens, adapts, and acts locally. Unfortunately, what we see today is not planning, but planning as a weapon.”

In times of misinformation, you need news you can trust. Click here to support our work, and power journalism that is truly in public interest.

Newslaundry is a reader-supported, ad-free, independent news outlet based out of New Delhi. Support their journalism, here.