Is “A24” an abbreviation? Might the name of the cult American indie film studio – behind modern classics including Everything Everywhere All At Once and Uncut Gems – actually stand for “A 24-Month Delay for the Brits”? UK cinephiles would certainly have you believe so. While A24 has become one of the most recognisable brands in movie-making since its launch in 2012, again and again British filmgoers are made to wait for their releases. The latest example of this is Friendship, a brilliant new black comedy starring Paul Rudd and the I Think You Should Leave star Tim Robinson. The film arrives in UK cinemas this month, eight weeks after Americans first began logging it on their Letterboxd accounts.

Eight weeks is actually a pretty snappy turnaround by A24 standards. In 2023, 98 days passed between Past Lives’ US release and its debut on UK screens. It was 119 for Barry Jenkins’ 2016 masterwork Moonlight. As for 2022’s Marcel the Shell with Shoes On? 238 days – a fittingly slow crawl across the Atlantic for a tale about an animated snail carapace. Alright, it’s not quite “A 24-Month Delay”, typically facing UK fans of the indie powerhouse. But in a borderless, lightning-paced online era where pop culture consumers are accustomed to instantaneous gratification, it can certainly feel that way.

Friendship isn’t the only example of A24 staggering their international releases this summer. Materialists, the new Celine Song romantic drama starring Dakota Johnson, hits UK cinemas on 15 August, having been entertaining US audiences since 13 June. The new Philippou brothers film Bring Her Back – their follow-up to the ghoulish thriller Talk to Me – is similarly enduring a two-month layover between destinations. But it’s not just A24. Want to see The Life of Chuck, Neon’s Stephen King adaptation about the end of the universe? After debuting Stateside on 6 June, that film won’t hit UK cinemas till 22 August – by which time the actual end of the universe could have unfolded, or so it probably feels like to fans of its director, Mike Flanagan.

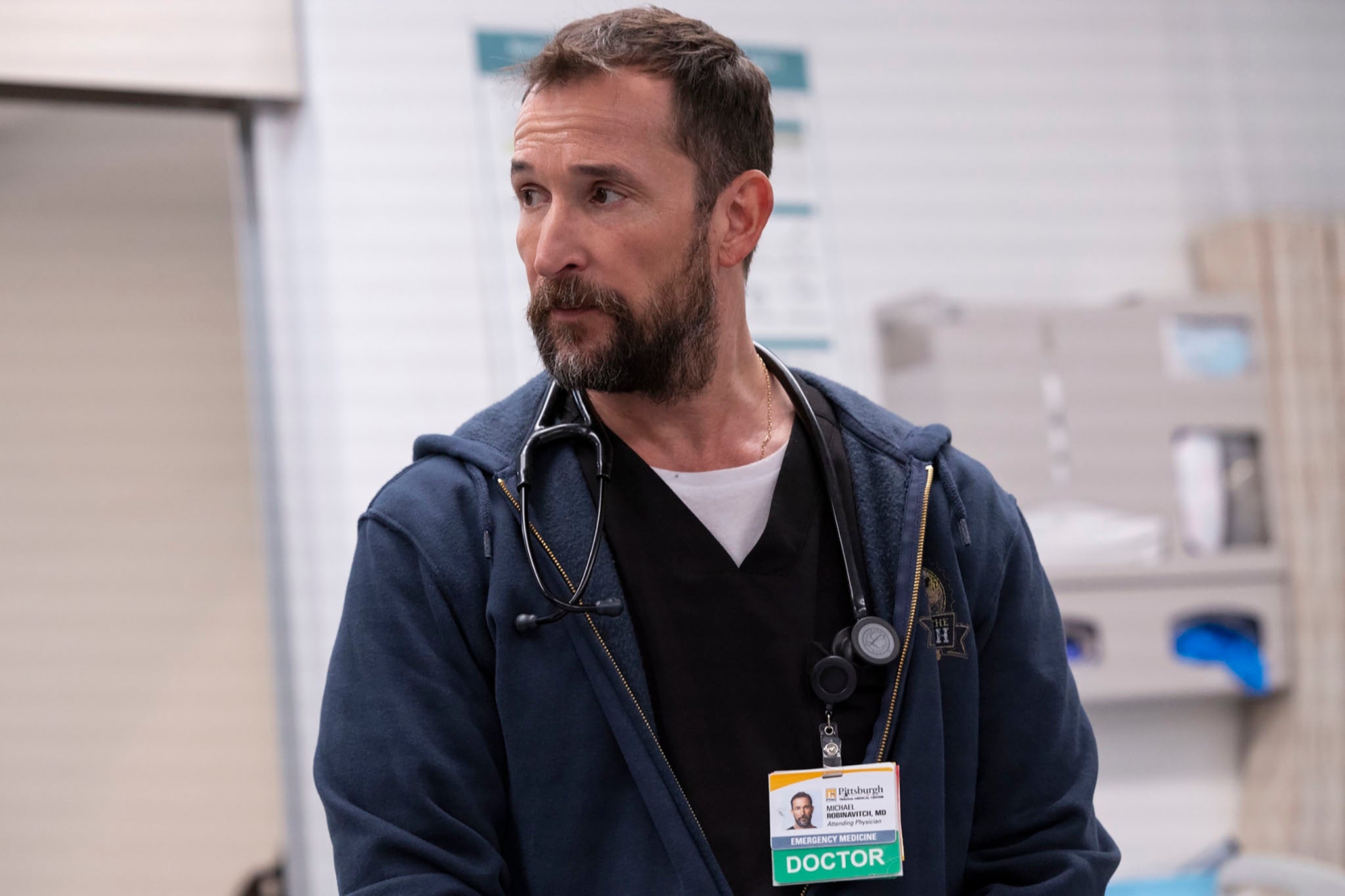

This is a problem on the small screen, too. Right now, UK viewers have no legal way of watching one of the year’s most talked-about US shows, The Pitt. The medical drama took home 13 Emmy nominations this week – including Best Drama and Best Actor for star Noah Wyle, returning to scrubs years after ER. But it’s highly likely that Brits won’t have had a chance to see a single episode by the time of the actual Emmy ceremony on 14 September.

Why is this happening? Are such delays helping or hindering a declining global film and TV industry struggling to compete with TikTok and other distractions? And should Keir Starmer insist on urgent trade talks with Donald Trump to put an end to this blight on the lives of UK pop culture aficionados? The answer is complicated (except for that last question, which is clearly “yes, immediately.”)

A24 fans wear caps with their logos on as symbols of their love of cinema. They’ll wait to watch ‘Materialists’ properly

“The first thing to say is that staggering releases is actually a return to the norm,” one publicist tells The Independent, speaking anonymously to protect their relationships with the studios they work with. Before the millennium, films and TV shows would regularly be released in one market before moving to the next, they explain. “[Movie stars] might sometimes play superheroes and Gods, but they can’t be in multiple places at once like them. They can’t do press in Brazil while attending a premiere in Italy before doing a Q&A in Japan on the same day.” Achieving anything like that feat – see the international press tours of this year’s Superman or Mission: Impossible – The Final Reckoning – comes at a steep financial and logistical cost.

With actors and directors integral to promoting a new release back then, just as they are now, there was a time when films would come out months apart in different territories, so that those stars could appear on local TV and radio. This led to even the biggest blockbusters hitting different nations in a staggered fashion; when Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace was released, for example, British Jedi enthusiasts reportedly flew in their thousands to America so that they could see the highly anticipated prequel on 19 May 1999. The film wouldn’t hit cinemas on home soil till 16 July. (“Imagine that now!” the publicist laughs.)

Then piracy happened. The film industry began scrambling to stop movies being downloaded by impatient fans from beyond the US, who no longer had to catch an expensive flight to experience new releases on opening day. Social media was in embryonic form at the time, with a new culture of movie fandom starting to blossom on internet message boards; with a dial-up modem and a bit of know-how, you could watch a film and then discuss it with like-minded obsessives, practically for free, from the comfort of your home. Staggering international releases was no longer a viable option for major blockbusters, not unless they were happy with a chunk of their box office totals being eroded because fans decided to hell with having to wait.

Sam Clements – head of marketing and membership at the Picturehouse cinema chain – points out that, in those days, major movies perhaps weren’t as heavily predicated on big twists as they are today, adding to the need to release them simultaneously. As a result, blockbusters today “aim for a ‘global moment’ to avoid any plot spoilers leaking out,” he explains. “For a studio film like Jurassic World Rebirth, the date is nominally the same. For more independent or international productions,” he continues – meaning films less reliant on shocks and surprise cameos – “there can be more disparity.” After all, no one is going to see Ari Aster’s challenging Covid dramaEddington to see if Robert Downey Jr turns up as Dr Doom in a post-credit sting that might be leaked on Reddit months before the film hits the UK.

For a studio like A24, the aforementioned publicist explains, “you have the ability to delay your releases and target each market one at a time. The profile of fan that they tend to have means you’re not as much at risk of piracy. A24 fans wear caps with their logos on as symbols of their love of cinema. They’ll wait to watch Materialists properly, on a big screen instead of some choppy streaming site with pop-up ads. They might complain about having to wait. But they will wait.”

The wait can often work in UK cinemas’ favour, Clements acknowledges, recalling how when the Daniels’ mind-bending odyssey Everything Everywhere All At Once hit cinemas in the US in 2022, “it opened to great fanfare but didn’t have a UK release date announced.” Had the film opened at the same time as in the US, it may have attracted dribs and drabs of moviegoers, some have speculated; in-the-know cineastes mostly, who’d enjoyed the director duo’s cult hit Swiss Army Man a few years earlier. Instead, the buzz generated during Everything Everywhere’s run in American cinemas meant that people were practically banging down the doors of UK multiplexes for word on its release here (“We definitely did get people asking us on social media about when the film will open,” Clements recalls). As a result, its box office is thought to have been greater across British cinema chains, because word-of-mouth had been allowed to build.

Delayed releases aren’t always a strategic choice. Sometimes the reasons behind them are to do with licensing rules and, frankly, they’re pretty dull. The Pitt is one such example. Makers Warner Bros are currently in a tangle with Sky ahead of the eventual UK launch of their HBO Max streaming platform; till now, an arrangement has been in place meaning that HBO titles automatically air on Sky Atlantic and Now TV in Britain, but not titles that air exclusively on HBO Max (I warned you it was dull). And now beef is ensuing.

A similar fate awaited another great show of the last five years, comedy-drama Hacks. The Jean Smart series eventually struck a deal to be shown in the UK on Sky and Now, but after an earlier pit stop on Prime Video and a delay of nearly a year before the UK finally saw its most recent season. The Pitt, too, will eventually be broadcast over here. And, when you think about it, it’s not really so long till Friendship, Materialists, The Life of Chuck and this summer’s other anticipated indie releases surface here, either. It’s just that the delay “can feel more pronounced in today’s digital media world, with critics and influencers and marketing from one location spilling out onto the global digital space,” as Clements explains.

Good things do come to those who wait – and British film fans should know. They’ve had plenty of practice recently.

‘Friendship’ is in cinemas from 18 July

Lead actor in The Pitt sheds light on why popular co-star isn’t returning

Michelle Yeoh confirmed for new version of one of the most successful movies ever

Think we live in the age of ‘blockbuster slop’? Try watching Superman

The next three weeks might decide the future of comedy movies

15 times directors ditched major blockbusters: ‘I’m not going to be happy doing this’

Spinal Tap invented the rockumentary – and its influence is everywhere you look