The first tranche of data on electoral bonds disclosed by the Election Commission of India on March 14, 2024, under the directions of the Supreme Court, provides an incomplete picture of the transactions that have taken place between various companies and individuals on the one hand and registered political parties on the other, between April 12, 2019 and January 24, 2024. The apex court has now directed the State Bank of India (SBI) to ensure “complete disclosure of all details in its possession” by March 21, 2024 including “the alphanumeric number and serial number of the Electoral Bonds which were purchased and redeemed”.

Unique alphanumeric numbers

The SBI has recorded every detail of 18,871 purchases and 20,421 encashments of electoral bonds between April 2019 and January 2024. However, in the absence of the unique alphanumeric numbers, only the total amount of electoral bonds purchased by each company or individual can be estimated as also the total amount of electoral bonds each political party has encashed; but it is impossible to establish who has paid whom and when.

The disclosure of the unique alphanumeric numbers becomes imperative because the apex court has struck down the entire electoral bond scheme as unconstitutional. It is only natural that the very large sum of ₹12,155.1 crore worth of electoral bonds, purchased by corporate groups, companies and individuals between April 2019 and January 2024 are matched accurately with ₹12,769.08 crore total worth of electoral bonds encashed by political parties during the same period. In other words, the people need to know which political party got how much from whom, and on which date(s). No further inquiry or investigation can be conducted into these “unconstitutional” transactions, without linking the purchasers of the electoral bonds with the encashers.

Information asymmetry

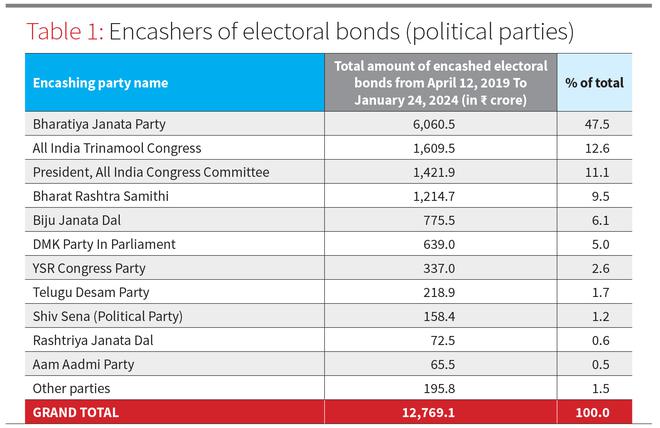

The Union Home Minister has countered the embarrassment caused to the government by the disclosure of the BJP accounting for ₹6,060 crore, that is over 47% of the total amount of electoral bonds encashed, by pointing at the amounts encashed by other Opposition parties (Table 1).

The problem is that the total amounts encashed in electoral bonds by the various parties neither reveal much, nor can they be cited as actionable evidence of corruption and malfeasance. It is only through an analysis of the granular details of the electoral bonds, like their amounts, dates of purchase and encashment and the linked identities of the purchaser and encasher of each bond that possibilities of quid pro quo can be hypothesised, investigated and legally established as evidence. This explains the reluctance of the SBI to reveal the unique identification numbers of the electoral bonds. The political strategy of the ruling party appears to be simple: stall any investigation or legal proceeding against any transaction till the end of the election campaign.

The Union Government, as the owner of the SBI, is already in possession of the entire electoral bond database, which implies that BJP — as the ruling party — has access to complete information in this regard. Both the Opposition parties and the electorate, however, do not. Each political party other than the ruling party, knows about its own transactions only. The voters have no information beyond what has been disclosed by the Election Commission of India. This information asymmetry provides the BJP with an undeserved advantage by virtue of its being the ruling incumbent.

This is similar to the non-disclosure of the politically sensitive data on the caste census, which was collected during Census 2011 but has not been released till date. The BJP has utilised the caste census data to its electoral advantage in every election held since May 2014, while the Opposition and citizens have been denied access.

Such abuse of power, through suppression of information and data that are public goods, should be prevented.

Preliminary analysis

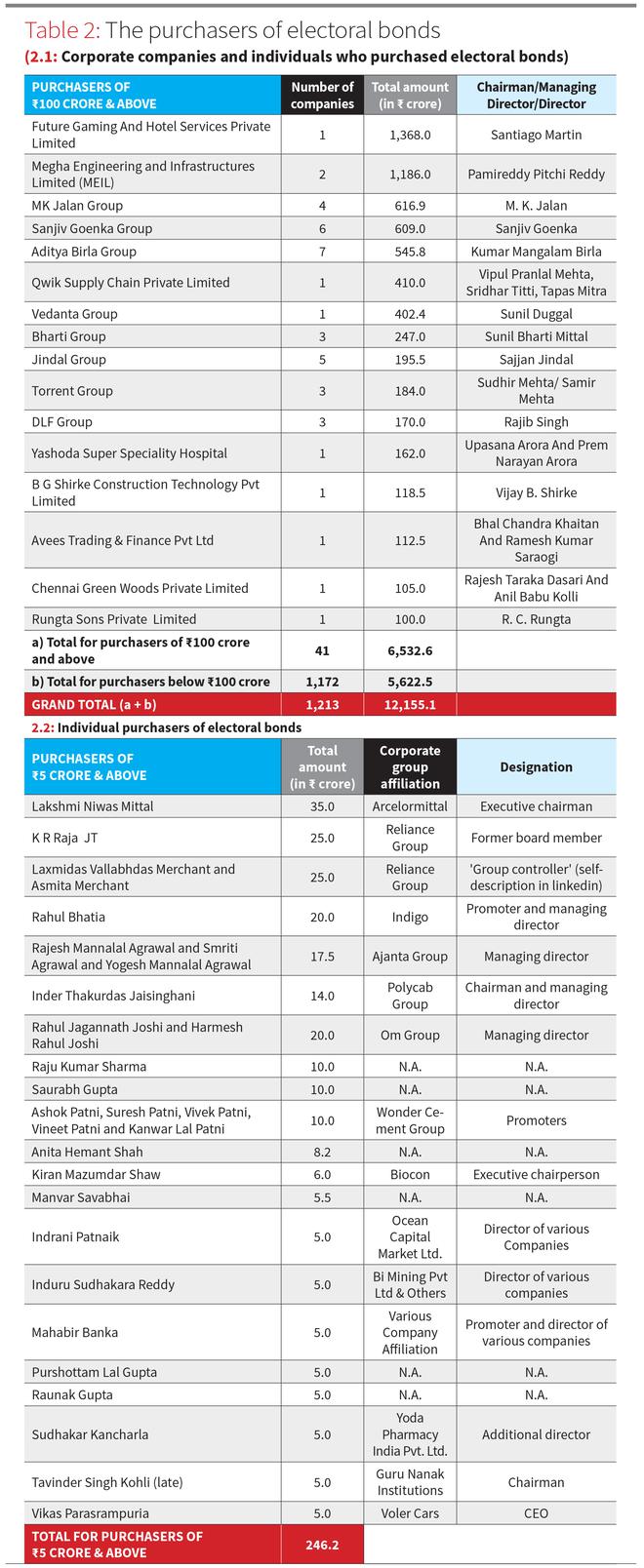

The data disclosed so far provides ample grounds for suspecting malfeasance. Table 2 provides a list of companies and corporate groups who have purchased electoral bonds worth over ₹100 crore in total between April 2019 and January 2024, along with a list of individual purchasers of the bonds totalling above ₹5 crore.

What stands out from the list are the following:

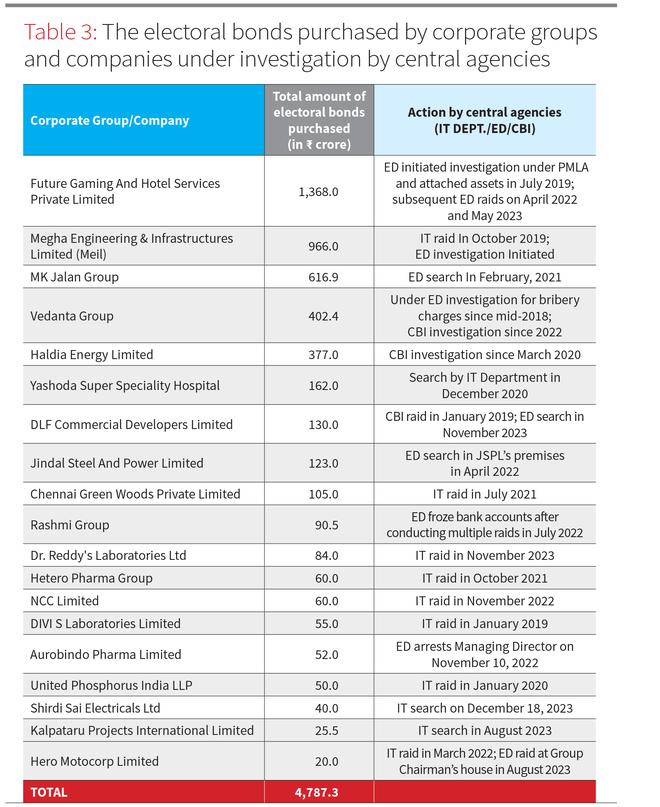

(a) Some of the largest purchasers of electoral bonds are under investigation by central agencies such as the Enforcement Directorate (ED), Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) and/or the Income Tax (IT) Department. Table 3 provides a list of 19 such companies which have together purchased ₹4,787.3 crore in bonds; over 39% percent of the total amount.

(b) The names common in Tables 2 and 3 are Future Gaming, Megha Engineering, M K Jalan group, Vedanta Group, Haldia Energy Limited (Sanjiv Goenka Group) etc. If the bulk of the electoral bonds purchased by these companies, which are under investigation by central agencies like ED, CBI or IT department, are found to have been redeemed by the party in power, that is, the BJP, it would imply serious conflict of interest issues and probable quid pro quo.

(c) The largest individual purchasers of electoral bonds are either heads of corporate groups and companies or their employees. It is clear that corporate houses and companies have tried to conceal their identities by deploying individual frontmen or making large donations in multiple small tranches. This generates suspicion of large scale bribery, money laundering and other forms of quid pro quo, like award of lucrative project contracts and policy changes in exchange for party donations.

As the party in power at the Centre and the largest redeemer of electoral bonds, the BJP has much to answer for. The Modi government has tried to evade such accountability during the Lok Sabha election campaign, first by delaying the disclosure of data and then by withholding the unique alphanumeric numbers of the electoral bonds.

The author is an economist and activist.