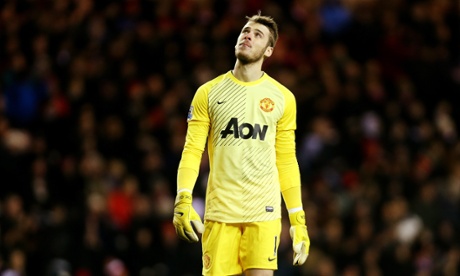

It’s not clear exactly what happened in the admin offices of Manchester United and Real Madrid football clubs on Monday night. Murmurs from Real claim that United sent over the transfer documents too late, or in a file format they couldn’t open, or that was protected with a password. Murmurs from United insist they did everything properly before Spain’s transfer window closed. All we know for sure is that Madrid have not bought David de Gea, the goalkeeper they desperately need; United will not get £29.3m for him in the next window (because they’ll lose him for nothing if they don’t sell); and poor De Gea, who had travelled back to his home city expecting his dreams to come true ... well, at least he won’t have to unpack.

Extraordinary as it seems, this fiasco should be a reminder that huge clerical mistakes happen everywhere, and regularly. In the financial markets, so-called “fat-finger errors” – when traders mistype their orders – have long been a menace. In 2005, a Japanese trader cost his brokerage, Mizuho Securities, $335m (£218m) when, instead of offering to sell one share for ¥610,000, he offered 610,000 shares for ¥1. Four years before that, a dealer for Lehman Brothers in London almost capsized the FTSE, which at one stage had lost £30bn in value, after he accidentally typed £300m instead of £3m. In April 2012, a German bank clerk actually fell asleep at his keyboard and ended up taking not €62.40 (£46) out of a pensioner’s bank account, but €222,222,222.22. Thankfully, that mistake was soon spotted and corrected, as was the biggest blunder of all time, when another trader in Japan very nearly bought £380bn worth of shares last autumn.

Admin oversights can also lead to important things being lost. In perhaps the worst case, on 18 October 2007, a junior tax official, who has never been named, sent a CD by courier from Tyne and Wear to the National Audit Office in London. The CD contained more or less the complete database of Britain’s child-benefit recipients, had only very flimsy password protection ... and never arrived, having not been sent by recorded post. When it became clear that the names, birth dates and addresses of virtually every child in Britain were now in the hands of whoever had found or taken that CD, the prime minister, Gordon Brown, had to apologise in parliament and the chairman of HMRC resigned. Less seriously, but just as staggeringly daft, the Bank of England managed this May to email the Guardian not just its secret plans for managing a British exit from the EU, but also its secret plans for denying that the plans existed.

If these seem like trivial losses, consider the case of Mike Anderson, a man who in 2000 was convicted of armed robbery in Missouri, but then never sent to prison. Rather than becoming a danger to society, Anderson made the most of his luck and got married, started a business, had four children and volunteered for his local church. Only in 2013, when he became due for “release”, did the state notice their mistake – and promptly put him in prison (only to release him again when the case became famous). Hopefully, Mike Anderson can be a comfort at this sad time for David De Gea.