Matthew d’Ancona (Opinion, 9 March) is right to suggest that the leader of any political party who refuses to participate in televised debates risks indicating to voters that “they are being taken for a ride or taken for granted”. The crude bluff and counter-bluff that has characterised the debate about debates reinforces the idea that politics is a Machiavellian game in which tactics are everything. This conflicts with the rather innocent, but worthy, ideal of politics as a space of democratic contestation in which the most forceful arguments and compelling values prevail.

For most people, casually looking in on the sordid debate about debates, the idea that it should be up to politicians to decide whether they fancy showing up to the event makes no more sense than assuming that political leaders should be allowed to decide whether to have an election campaign. In my extensive research on what people want from the 2015 election debates, it became clear that most of them regarded these as a newly established part of the constitution. When I told people that the debates had to be negotiated in a series of protracted secret meetings, they were genuinely shocked. Shocked for a while – before reverting to a default disappointment, as if suddenly realising that these debates were yet another example of politicians hijacking democracy.

My fear is that this whole sorry fiasco reflects a deeper cultural uncertainty about what it means to have a meaningful debate. In an age when ministers saying “We need a national debate” really means that they and their shadows should tour the broadcast studios exchanging facile soundbites, the very idea of a direct, forceful clash of ideas seems somehow exotic. Political leaders who imagine that the value of democratic debate is best measured by how little damage it would do to them must accept a large share of responsibility for the public’s disengagement.

Professor Stephen Coleman

Professor of political communication, University of Leeds

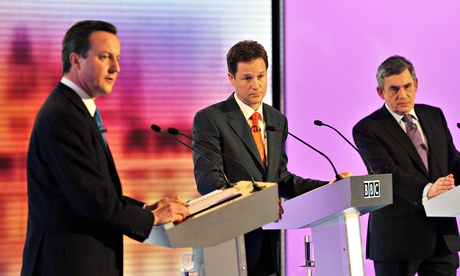

• David Cameron’s cavalier attitude – strangely different from his eagerness for television debates before the last election – is an insult to our right to judge each leader and party both on their records and on their manifesto promises to us for the next five years. The broadcasters, on our behalf, should stand firm and call his bluff.

Laura Phillips

London

.jpg?w=600)