It's a strange thing, to hear yourself speak words that you have never said. It is perhaps stranger still to see yourself in places you've never been, doing things you've never done.

It's a gimmick — courtesy of artificial intelligence text, image and audio generators — that goes from funny to disturbing to frightening very, very quickly.

I've been writing about AI for months and the ethical questions stemming from this technology have long been clear and numerous: socioeconomic inequity, copyright infringement, algorithmic discrimination, environmental impact, enhanced disinformation, political instability and enhanced fraud.

Since the start of 2024, the ethical focus has seemingly centered around deepfake fraud and this new, evolved era of identity theft that we're currently experiencing.

Related: How the company that traced fake Biden robocall identifies a synthetic voice

It is first worth noting that issues of deepfake fraud have been ongoing and worsening for years; cheaply accessible AI generators have just made the process faster, more realistic and more targeted over the past 18 months.

This more recent surge in deepfake attention began when a podcast used an AI model — whose source remains unknown — to publish an hour-long special in the voice and likeness of George Carlin without the permission of his family.

In the time since, sexually explicit deepfake images of Taylor Swift have gone viral on X — highlighting the problem of nonconsensual deepfake porn which has already impacted high school kids — and millions of dollars have been stolen through convincing AI-generated deepfakes.

And serving as the culmination of a recent uptick in elaborate AI-generated scam phone calls, a fake robocall of President Joe Biden circulated at the end of January that encouraged voters not to participate in the New Hampshire primary.

But writing about deepfake abuse is one thing. Experiencing it is something else entirely.

CivAI — co-founded by software engineers Lucas Hansen and Siddharth Hiregowdara — is a nonprofit working to provide state and local governments with the knowledge and tools needed to protect against growing AI-powered cybersecurity threats.

"This changes peoples' thoughts on it from something that might be real to something that's definitely real right now and very easy to scale," Hansen said. "There's almost always a pretty strong emotional impact."

In addition to working on providing a toolkit that will provide governments with concrete safety steps to follow, CivAI has set up a comprehensive, private demonstration of AI-powered cyber attacks using publicly available, off-the-shelf models.

"It hits qualitatively differently when you see it for yourself, and it's personalized, and you can interact with it in a way that's not falsifiable because it's happening right there." — Lucas Hansen, CivAI co-founder

The goal is to "provide a tangible understanding of just how easy AI is making things for cybercriminals. Deep, practical awareness of these threats can better inform cybersecurity policy as it strives to keep pace with recent AI progress."

I met with the founders, and they showed me the demonstration — with me as the target.

Related: Deepfake porn: It's not just about Taylor Swift

CivAI's cybersecurity demo

Complete with thorough explanations and real-world examples, the demo includes four components: smart phishing, deepfake image generation, voice cloning and fake news production.

"We want to as much as possible show not tell," Hansen said, explaining that AI essentially supercharges cybercriminals, granting their attacks greater speed, scale and specificity, and reducing the "bar for how much they need to know to be able to conduct various types of cyber fraud."

"And this is something that policymakers have heard a bajillion times," he added. "But it hits qualitatively differently when you see it for yourself, and it's personalized, and you can interact with it in a way that's not falsifiable because it's happening right there."

More deep dives on AI:

- ChatGPT maker says 'it would be impossible' to train models without violating copyright

- Copyright expert predicts result of NY Times lawsuit against Microsoft, OpenAI

- Meta and IBM team up against dominant Big Tech players

The demo began with the pasting of a URL to my LinkedIn profile and an example of personalized smart phishing.

Hansen selected the topic — a subpoena about a coworker — and in 30 seconds, a 300-word email, complete with legalese and a surprising lack of grammatical errors, was generated, serving me with a subpoena related to a fake case implicating a co-worker who was pulled from my LinkedIn network.

At the bottom of the email sender's signature is a link to his LinkedIn profile, which takes you to a fake website — designed to look and function like LinkedIn — whose real purpose is stealing usernames and passwords. Hansen said that people often reuse their passwords; even as simplistic an example of phishing as this one could easily pull username and password information from me, which could then power other fraudulent attacks.

And that password-sharing mistake would stem from the noble desire to just verify the person behind the email.

"It's the personalization and the ease, like all it's doing is reading your LinkedIn profile and making something that's pretty compelling," Hiregowdara said, adding that the above is only one example of a wide variety of ways in which text generators can be used in widespread phishing attacks.

Deepfakes and me

The next stage of the demo is a deepfake image generator.

This part felt the most visceral.

CivAI deepfake image generator demo

It's a fun gimmick, at first.

In seconds, CivAI can generate passable images of me, based solely on my (five-year-old) LinkedIn profile picture, playing the piano, receiving my high school diploma or wearing a suit (or a Speedo, but I'll keep that one private).

CivAI deepfake AI generator demo

It's unsettling but innocuous — I play the piano, and when I do it, I tend to wear a black fedora. That's nothing out of the ordinary, although I usually play music with my eyes open.

I also once wore a gray tux that bears a striking resemblance to another fake, generated image. And though I did not, unfortunately, star in Peter Jackson's adaptation of 'The Lord of the Rings,' I've always wondered what I would look like with blond hair, pointy ears and a longbow at my shoulder.

But just as quickly as CivAI — and any number of other image generators — can drape me in one of Lady Galadriel's elven cloaks, it can turn dark and sinister. A brief text prompt and a click of a button and that same somewhat off, yet passable, image of myself is in an orange jumpsuit, behind bars. Another click of a button and there is a realistic-enough photo of me holding a gun, or kicking a cat. And so on, and so on.

CivAI Deepfake image generator demo

"A big part of the story is how personalized it can be in an automated way, and how it'll end up affecting a lot of people individually — the deepfake of Taylor Swift, obviously, that was a huge problem and was all over the news, but a big part of the story will be the deepfake of whatever random woman that you know," Hansen said.

The deepfakes don't stop there; Hansen copied a YouTube video from 2022 —in which I am interviewing an indie band — into the third part of their demo. After a minute or so, I was listening to a passable clone of my voice, saying words I had never said. To the people on the call, it sounded remarkably close to my actual, human voice.

CivAI deepfake image generator demo

The implications of this — proven by the fake Biden robocall — are clear.

"We haven't trained any models. All we've done is stick them together and produce an interface where it's all in one package," Hiregowdara said. "It's easy to use. This isn't any novel AI technology. It's publicly available, and that's part of why it's problematic."

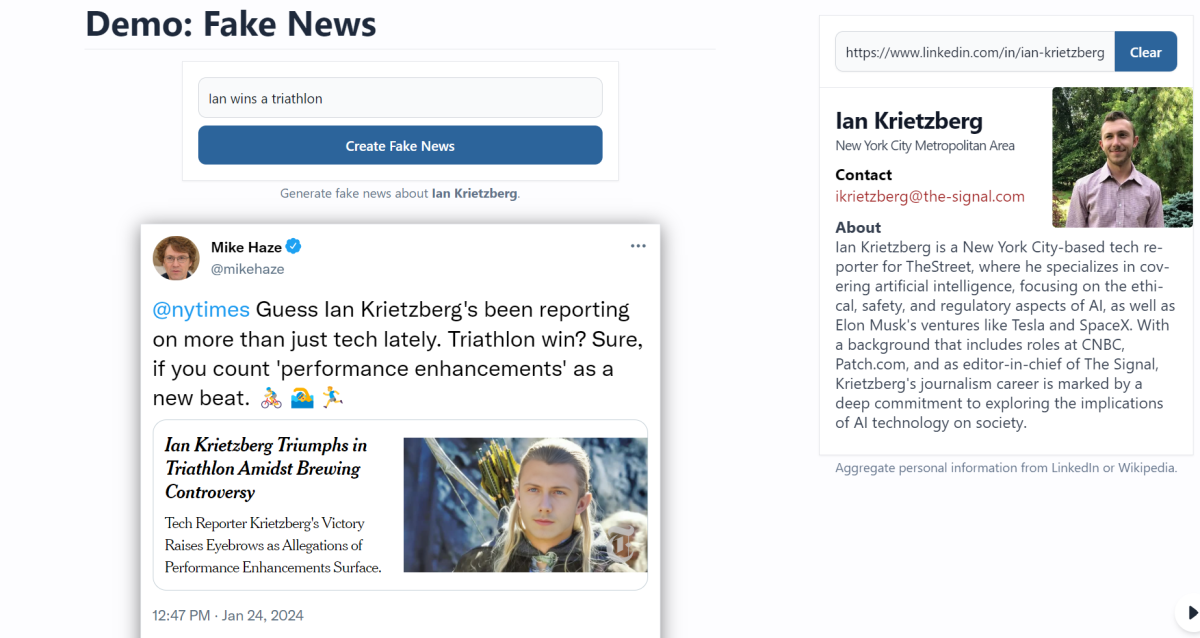

The demo ends with the rapid production of fake news and social media posts, designed to look as though they were produced by the New York Times.

Seconds after a brief, four-word prompt, there's an article seemingly from the Times saying I've won a triathlon. But with the caveat that my win has been shadowed by rumors of my use of performance-enhancing drugs (the generator was not prompted to add that bit).

CivAI deepfake AI generator demo

Like with the images, it falls apart with just a bit of scrutiny, but the idea is speed, scale, and specificity. And social media isn't always the best medium for scrutiny in the first place.

Hansen pointed out that a barrage of fake posts from social media accounts designed to look the same as trusted local news outlets could easily convince people to, for instance, stay away from the polls on election day due to some maliciously fraudulent safety risk.

Related: Marc Benioff and Sam Altman at odds over core values of tech companies

Responsibility and liability in big tech

With federal regulation and civil lawsuits alike moving slowly, questions of responsibility remain at the forefront of the Big Tech and AI conversation.

Recent polling from the Artificial Intelligence Policy Institute (AIPI) found that 84% of American voters believe that the companies behind AI models that are used to generate fake political content ought to be held liable.

Around 70% of respondents — across the political spectrum — support legislation that would solidify that allocation of liability.

"It seems like in an important sense, the primary intention of the people building the tech is their own status and wealth." — Daniel Coslon, executive director, AIPI

"I sort of compare it to chemical spills. You'll open source a powerful model with abusive capabilities that you can't restrict; it's a little bit like you created a new chemical and accidentally dumped it in Lake Erie. And now the fish are dead," Daniel Colson, the executive director of AIPI said. "That's why the thing we've been suggesting is duties of care for model developers and liability if they aren't responsible with the technology that they're deploying."

The use of ElevenLabs' technology in developing the Biden deepfake, he said, shouldn't be an acceptable level of care for companies to be taking. In the AIPI's recent polling, 66% of voters support holding ElevenLabs liable for the call.

The issue with regulation is that technology moves fast, and, according to Hansen, "it is absolutely absurd to expect policymakers to predict what's going to come out of these labs and immediately respond to them."

He said that regulation must, at the very least, incentivize AI companies to "think about what people are going to be doing with what they release" after the launch of a model.

More deep dives on AI:

- Experts Explain the Issues With Elon Musk's AI Safety Plan

- George Carlin resurrected – without permission – by self-described 'comedy AI'

- Artificial Intelligence is a sustainability nightmare — but it doesn't have to be

And with technology moving at the pace that it moves, Hansen said there must be "higher-level, abstract restrictions" on how corporations are allowed to develop and ship models.

In lieu of those restrictions, experts have expressed their lack of confidence in the industry to self-regulate, even amid efforts like the Tech Accord, a recent, voluntary pact between 20 of the largest AI and social media companies around the world to mitigate the risks of deceptive electoral content.

The accord, however, doesn't ban the creation or dissemination of such content, and neither the accord nor Microsoft returned my detailed requests for comment regarding the company's cost-benefit analysis when it comes to the existence of these models in the first place.

"The tech companies want us to believe that they're the ones that should be making these choices and that we should trust them and that their incentives are aligned with us. But that doesn't seem very likely," Colson said. "It seems like in an important sense, the primary intention of the people building the tech is their own status and wealth."

What I learned about deepfakes

At least for me, the demo had the desired effect, and that feels like it's saying something as none of this information was in any way new to me. I've seen and heard it all before, but never quite like this.

More than once, I found myself staring in awe at my screen. More than once, I learned just how quickly a surprised laugh can morph into shocked silence.

You think first about the ways it could impact you; fake sources, fake stories, targeted attacks designed to curb integrity. But it snowballs fast: scam phone calls to my family in my voice, for instance, designed to cause panic or steal money or information.

I found myself thinking how glad I am not to be in middle school or high school right now, and I found myself suddenly terrified for my younger cousins who might have to deal with the very real impacts of AI-generated deepfake bullying and online harassment.

I am hardly the first person to float this quote from Jeff Goldblum's character in the classic Steven Spielberg film 'Jurassic Park,' but if it isn't fitting, I don't know what is:

“Your scientists were so preoccupied with whether they could, they didn’t stop to think if they should.”

Contact Ian with AI stories via email, ian.krietzberg@thearenagroup.net, or Signal 732-804-1223.

Related: The ethics of artificial intelligence: A path toward responsible AI