Ali Akbar of Rawalpindi, Pakistan, has been hawking newspapers in Paris’s Left Bank district for more than five decades. While sales are dwindling, the job has allowed him to lift his family out of poverty and earned him a knighthood – a testament to a local legend, and the end of an era.

Akbar’s been treading these pavements since 1973. He started out selling Charlie Hebdo and Libération, then Le Monde – which he still pedals seven days a week from around 3pm to midnight.

Keeping up with Paris’s last paperboy is a feat in itself. "I walk between 12 and 15 kilometres a day. That’s why I’m so thin," says the spindly 73-year-old as he darts from one café terrace to another, shouting "Ça y est!" – "That’s it!"

His route takes us through cobbled streets lined with art galleries and bookstores, past literary cafés like Les Deux Magots where Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir and Ernest Hemingway once debated, and the Brasserie Lipp, where waiters carrying silver trays give a respectful nod and move aside to let him in.

"Ça y est! France is saved," he shouts, adding an ironic twist to the country's worst political crisis in decades.

Some people smile, others remained glued to their smartphones. The odd person buys a paper.

Listen to Ali Akbar on the Spotlight on France podcast:

A dying trade

Times have changed since the 1970s and '80s, when Akbar could sell around 200 copies a day. Now it’s "20 or 30" at best.

"It’s the internet," he explains. "Young people don’t read papers anymore."

To keep the flame of this dying trade alive, Akbar has developed his own theatrical style, inventing humorous or exaggerated versions of the day’s headlines.

“When Bill Clinton had an affair with Monica Lewinsky, I started to announce: 'Monica is pregnant by Bill, she’s got twins'. Or: 'Nicolas Sarkozy’s [wife] Carla Bruni has run away with [singer] Benjamin Biolay'… People laugh.”

He tries out the Lewinsky line in English at the Deux Magots – a popular haunt with Americans. It raises a smile or two but delivers no sales.

He pirouettes on one leg to check there isn’t a customer he may have missed before darting off to the next destination.

Does Paris's most picturesque neighbourhood need protecting from overtourism?

France's highest honour

Akbar bulk-buys Le Monde at half price at a regular kiosk and sells it full price at €3.80. It's a miserable hourly rate if you only sell 20 copies a day, but a decent top up to his monthly pension of €1,000.

In any case, he claims his main motivation is not financial but "to keep busy and stay in shape".

And to stay in contact with people. Everywhere he goes, people seem to recognise him – they smile, shout hello, pat him on the shoulder, lean out of car windows to shake his hand.

"I’ve become a bit of a legend in the neighbourhood," he says. And while St Germain has "lost its soul" as old residents gradually give way to tourists, he still clearly gets a kick out of his job.

“I bring joy for them. It’s not a question of money, I just want to bring something positive for the public.”

Akbar’s fame, if not fortune, has grown further since President Emmanuel Macron awarded him the Legion d’Honneur – one of France’s highest awards – earlier this year in recognition of services to the state. He's still waiting for the medal but says he's "very, very honoured" to be decorated.

"It's good for my image," he says, explaining that to many, people who work in the street are invisible.

"This will help to heal my wounds, my injuries. I’m an injured man."

From rags to more rags

Over a coffee at the La Perle hotel, where he leaves his stack of newspapers and bicycle every afternoon, Akbar lets his cheery veneer drop to reflect on hard times.

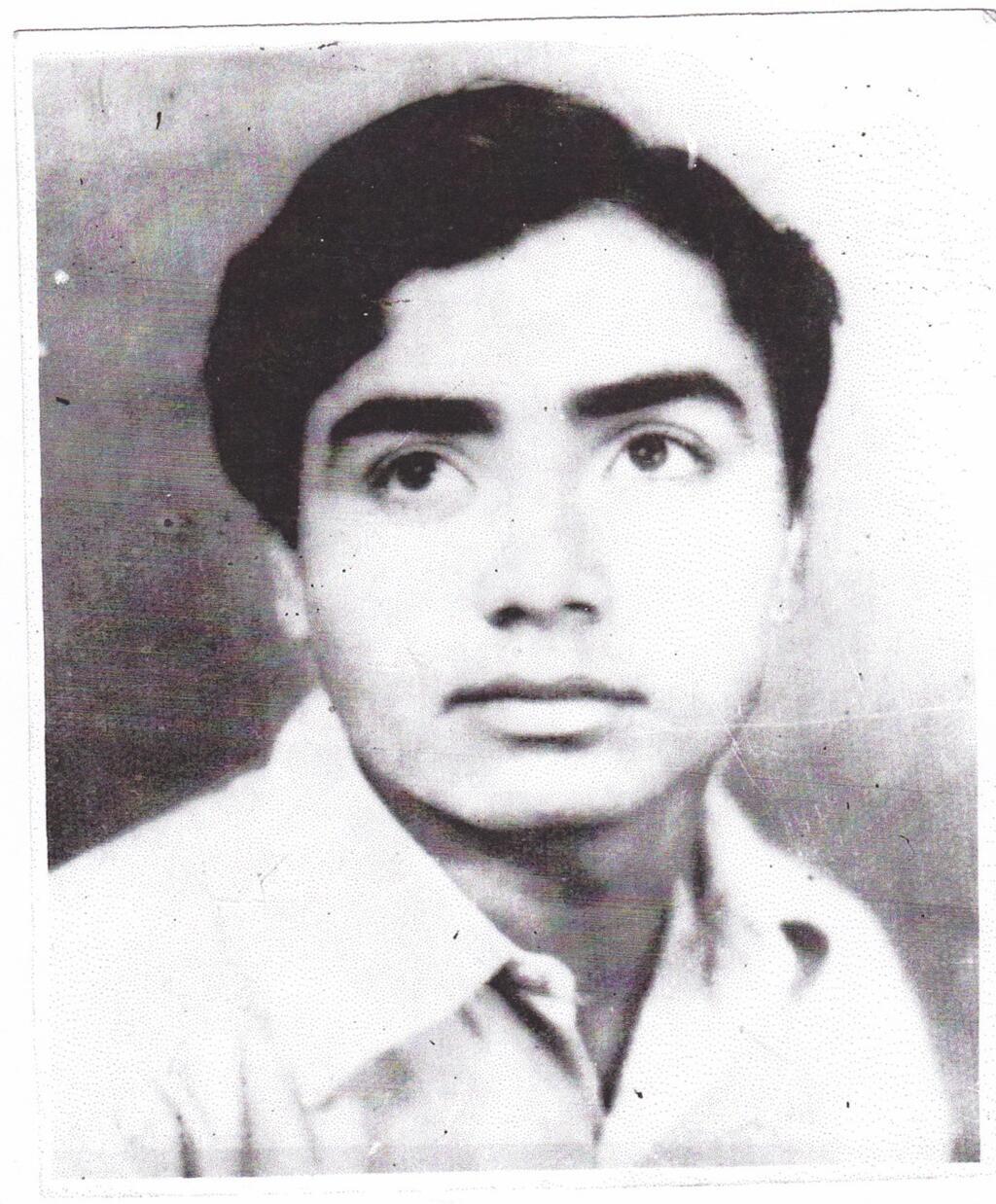

The oldest of 11 children, born to illiterate parents, he was raised in poverty. He had limited, mainly religious, education until the age of 12, and like many schoolboys suffered abuse.

In 1971, aged 18, he got a bus out of Pakistan, promising to earn enough money to build his mother a house.

He travelled through Afghanistan, Iran and on to Greece, where he began working on ships as a steward and cleaner. He was mocked for his Muslim habits and learned to soften their edges to get on.

After two years sailing the Mediterranean, he docked in the northern French port of Rouen. Unsure of where to go and not speaking a word of French, he decided to hitch a lift to Paris.

The guy who picked him up drove him into a forest. "I knew I was in danger. I tried to open the door but the man had a revolver," he recounts. Akbar was sexually assaulted at gunpoint.

"I was 20, I hadn’t even been with a woman. I was saving all my money for my mother," he says. "I was traumatised."

His one-month visa had run out, he was afraid the police would deport him. So he said nothing.

"For the next two months I didn’t feel well," he adds, lowering his head and voice.

And then the jokey Akbar resurfaces to counter any trace of self-pity. "At least he didn’t kill me, he let me live," he laughs.

The paper trail

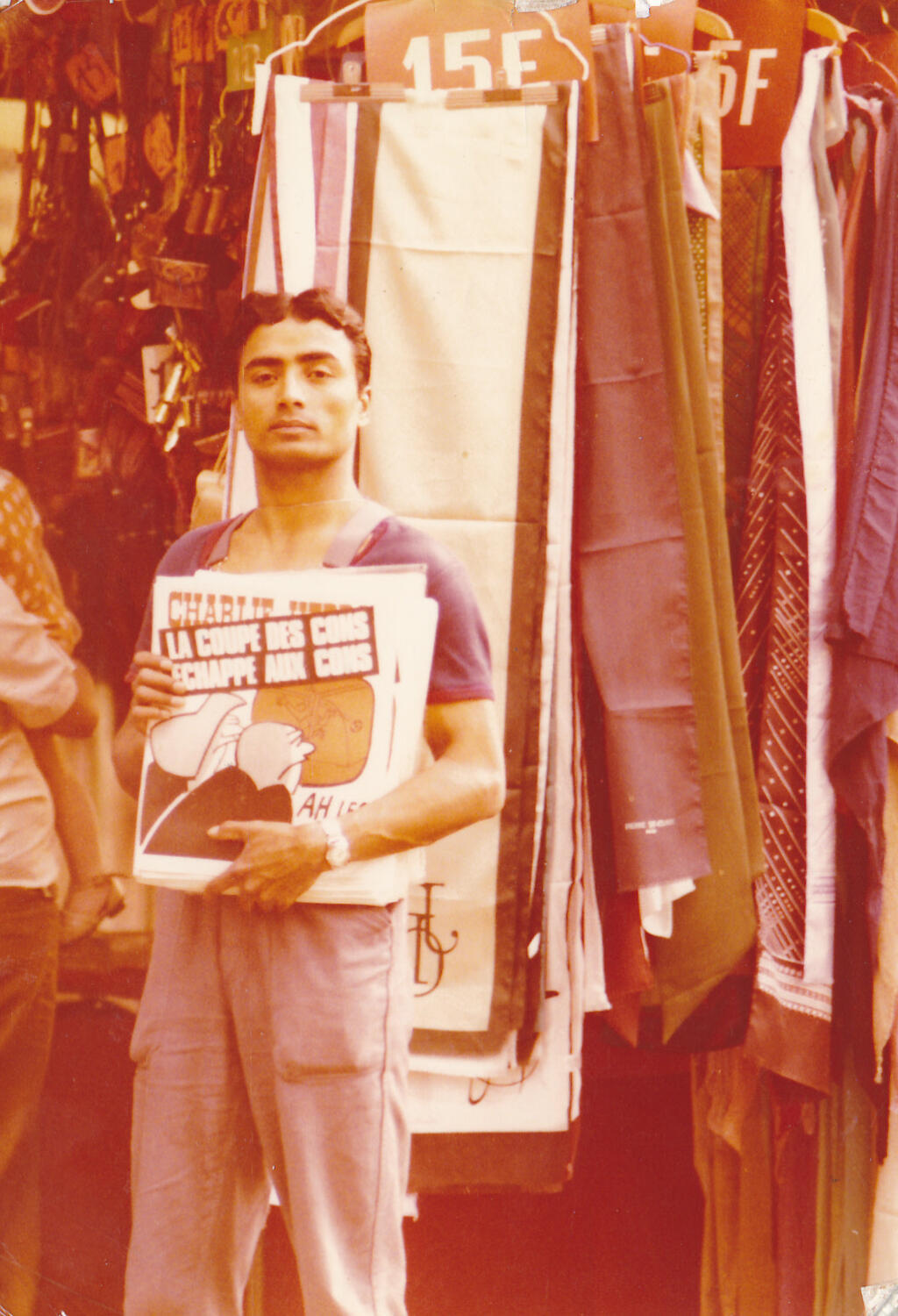

When Akbar arrived in the capital he had "no intention" of staying, planning instead to get back to Greece and the high seas. But a chance meeting with a student from Argentina who was hawking copies of satirical magazines Hari-Kari and Charlie Hebdo in St Germain des Près changed his future.

"I was shocked, the magazine showed a picture of a woman with a bare bottom," he says referring to the now-defunct Hara-Kiri, before admitting he was "curious" how this foreign student could make money shouting on the streets.

He was introduced to the magazine's founder Georges Bernier, who also owned Charlie Hebdo. Before long he was selling Charlie Hebdo, then Libération.

When, in 1976, students from the nearby Sciences Po university started asking him for Le Monde, Akbar’s entrepreneurial spirit kicked in and he began selling mainly that daily, which comes out in the afternoon.

Some of his customers, like students Emmanuel Macron or Edouard Philippe, would become famous. Others, like François Mitterrand, already were.

Basement blues

Akbar was making money, but sent the lion’s share back to Pakistan. So for about six years he slept rough.

"I had money, but not sufficient money to afford the hotel and send money to my mother, so I used to sleep under the bridge," he says. For five nights a week, he camped out in the basement where his boss stored the newspapers, "on a pile of curtains in a sleeping bag".

That changed when he got married. He now has five children.

In 2021 he tried to branch out from newspapers and run a food truck near the Luxembourg Garden, helped on by friends and well-wishers who organised a crowdfunding operation.

It proved to be another "horrible" experience. One of Akbar’s sons – who was supposed to come into the business as a partner – walked out on him. The replacement partner swindled him.

"I lost everything," Akbar says. "But it doesn’t matter, it’s only material things."

Inside the Paris hub offering sanctuary to city's army of delivery riders

A life in print

In 2009, Akbar documented his eventful life in a book. The English version, titled "The Last Paperboy of Paris: I make people laugh. The world makes me cry", is due out at the end of the year.

He describes the book as a form of therapy, and hopes it will serve as a lesson that "we can succeed by struggling and fighting every day".

"If you have a goal, a vision, you can do so many things," he believes.

Akbar achieved his goal. Not only did he build a proper house for his mother, he’s helped all the family back in Pakistan. "I’m not a politician, I’m not well educated, I didn’t do anything through words, I did all of this physically. I’ve been working hard, day and night, to [help] my family survive."

Barring accidents, Akbar has no intention of retiring. "I love my freedom," he says, and unlike in Pakistan, "no one is commanding me".

He adds: "I won’t stop 'til I drop."

Hear this story on the Spotlight on France podcast, episode 133.