While we here at MusicRadar often zoom in on the finer details of a song, or a mix in an effort to illuminate how you can sound as pro as possible by using today’s gamut of technology, instruments and tools, when it really comes down to it, your primary drive to make music can stem from a far more intuitive dimension. The best solution to keep that creative aspect nourished is often to just put the problem track to one side.

Headache-inducing barriers to completion are going to be inevitable from time-to-time when you're an active music-maker, but the best way to improve as a songwriter (or, as a creative music producer) is to keep that wheel turning, and not let these issues freeze you in your tracks.

Any technical or structural pitfalls you encounter shouldn’t form unbreakable, quick-set mud that prevents you from generating more ideas, nor should these issues gnaw at your self-confidence.

Around the internet and in academia, songwriting professionals preach the gospel of ‘just get it done’ - finishing the track in a potentially unsatisfactory way just so it’s completed.

This hypothetical problem track might be inches from brilliance, so the thinking goes, but think about how perfect the one you’ll write next will be - and you’ll also be equipped with the foresight to avoid the problems that you encountered here.

It’s an understandable philosophy if your discipline is more aligned with being a commercially-angled, song-crafter for other artists. In my view, being a songwriter or music-creator shouldn’t really ever be treated strictly as a skillset acquired by rote repetition.

The best work - for both self-releasing artists and songwriters-for-hire - comes out of the channelling of genuine emotion, experience and influences to invent a unique, new piece of art.

If the song feels like it’s going somewhere potentially special, but it might take time to get there, then there’s no harm in stepping away for a while (a day, a week, a month - even a year) and starting up another track.

Lesson #5 - Don’t let issues with your tracks slow you down - try to keep writing other songs and re-approach the problem track down the line

Something I have recently been reminded of, in my endeavours to make a new album, is that the more thorny issues with an arrangement, a melody or a mix are rarely rectified by just sitting in front of the DAW or instrument, continually throwing different sonic ideas at the wall. That's a surefire route to finger-biting frustration.

Solutions often manifest when doing different things - walking around the neighbourhood, reading a book, taking a shower or (and particularly) writing or working on other tracks.

Suddenly, that elusive section just blinks into existence, seemingly spurred on by nothing at all - yet your subconscious has been busying itself behind the scenes without you knowing.

In this detached context, you’ll find a piece of music, a riff or motif that could slot perfectly into the problem song, resolving its issues. Whilst also being some way towards penning a new track too.

But while many songwriting professionals would advocate the hurried completion of whatever you’re currently working on, and the continual writing of lots of songs to keep up the craft element of the vocation, my own angle here can only come from the attitude towards song/track-writing I have as a creative musician, and, to reiterate, that’s largely based on material that is being fuelled by emotion.

The ‘craft’ element, as important as it is, comes later.

But, the problem is, those song-triggering, deeper starting points aren’t always as readily on-hand.

It’s an approach that Neil Young seemed to be directed by, too, telling Paul Zollo (in his brilliant Songwriters on Songwriting book) that “Usually I sit down and I go until I’m trying to think. As soon as I start thinking, I quit, then when I have an idea out of nowhere, I start up again. When that idea stops, I stop. I don’t force it. If it’s not there, it’s not there, and there’s nothing you can do about it. There’s the conscious mind and the subconscious mind and the spirit. And I can only guess as to what is really going on there.”

Young is wary of the rational, problem-solving mind taking hold of more abstract ideas that originate from a murkier part of his subconscious, and is hyper-aware of the nullifying effect that trying to overly hone or shape the idea into a palatable song-form can cause.

Neil, implies that the germ of the song comes from somewhere else, and that he needs to be tuned-in to receive the information.

A fanciful idea perhaps, if taken literally, but it's a notion that jibes with the apparent pull to write music that stems not from technical prowess or the desire to build something for the sake of itself, but from a need to express.

In these cases, where a great developing piece has hit the brakes, a need to ‘widen the receiver’ is needed.

For Neil, his realisation that stepping away and leaving the song alone could lead it to internally grow within his own subconscious is itself a creative, practical strategy. Albeit one that respects the more unspeakable mystery of creativity.

Planted away within the deep recesses of his mind, Neil’s problem song can begin to sprout leaves, and eventually flourish.

Neil then, is still engaging in a sort of proactive strategy to move the song to the next level. And, one that's much better than sitting with a guitar until the early hours, losing patience and getting increasingly frustrated.

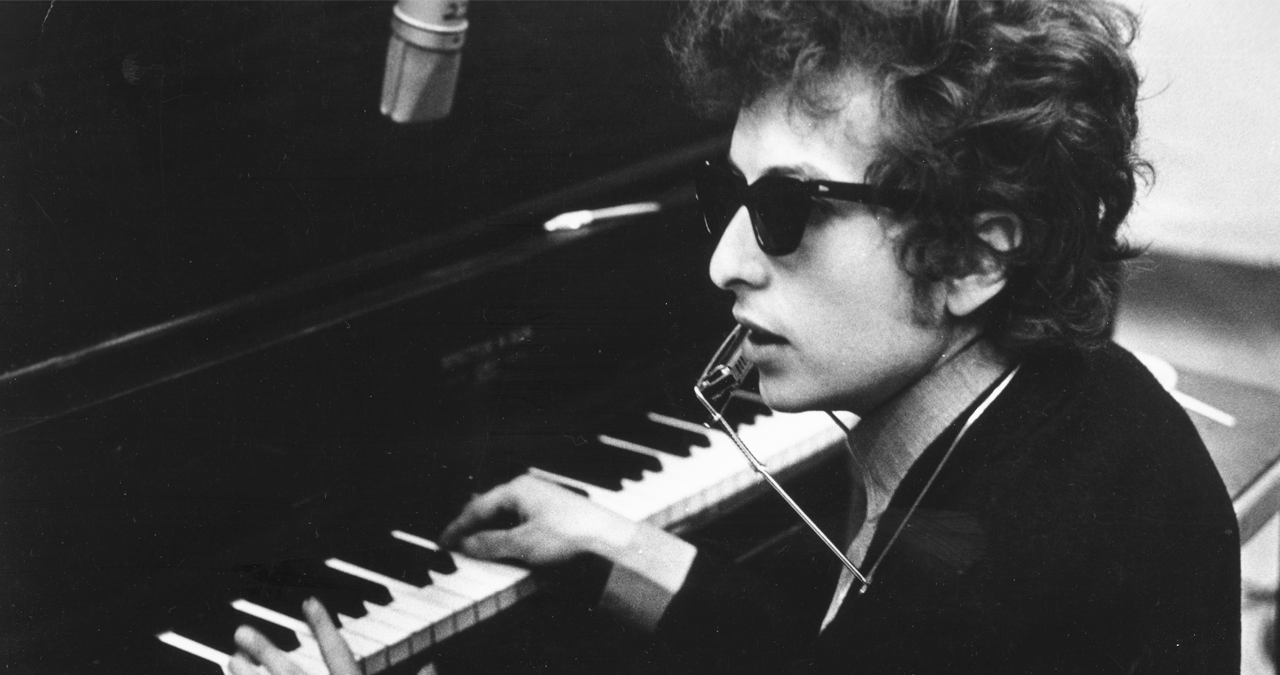

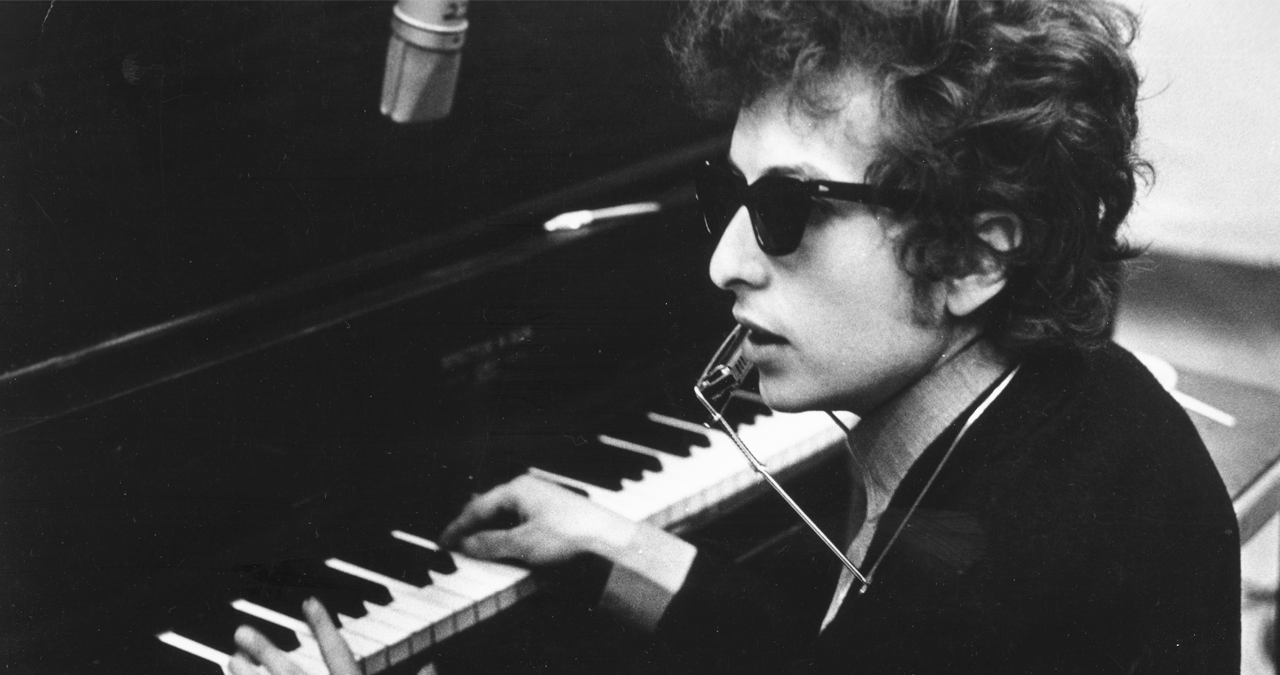

This attitude to the process is mirrored by the great Bob Dylan, telling USA Today in 1995 that “Creativity isn’t like a freight train going down the tracks. It’s something that has to be caressed and treated with a great deal of respect. You’ve got to program your brain not to think too much”.

While not 'thinking' too much might seem counter-productive, Dylan is referring to thinking technically about song structure, hurrying to slot a new idea into a format that might cheapen and weaken a more alluring starting point.

Of course, you can’t just sit around thinking about tracks in-progress the whole time, as a songwriter, you do have to eventually sit down and finish the damn thing. But that time doesn't have to be right now.

For every song with an elusive chorus, a thorny middle-eight or a lyric that you just can’t find the words for, there’ll be another that just seemingly drops, fully-formed, from heaven. Or another, where every track element you trial in your DAW slots together perfectly - and with a minimum of fuss.

Again, Dylan says; “The best ones are written very quickly. The longer it takes to finish the song the more difficulty it takes to pin it down and focus in on it and lose your original intention. I’ve done that a few times. I sort of just leave those songs go.”

Dylan is conscious of the dangers of over-coddling a piece of music, and the importance of keeping pace, moving on and keeping his artistic momentum up.

The success of the music-making process really hinges on the belief of the artist in the track they’re making. Losing sight of that, and scrabbling to get things finished when they’re not ready can, in my view, result in withered husks of tracks that could, if left to percolate a little longer, have been majestic.

You can’t force a problem song into shape - and neither should you spend too long obsessing over which direction to take to its completion.

Take a leaf from Dylan and Young’s book, and park the song up for a while. When it’s ready, the song will tell you.