Critical labour shortages are the catalyst for companies to finally automate and boost our decades-long productivity stagnation.

On December 19, 2013 a 20-year-old Levin man, Lincoln Kidd, was crushed to death by a falling tree – the 10th forestry worker to die in a single year; the 27th in four years.

Forestry was setting the wrong sort of records. There were so many deaths, the industry had its own dedicated coroner.

Enough was enough. As the media waded in and the unions launched high-profile campaigns, the Government finally called for an inquiry.

The industry’s legitimacy, its social licence to operate, was on the line. Companies needed to dramatically improve their safety record.

The way to do it was to get people off the ground. Everyone knew having workers in big machines with reinforced cabs kept them much safer than having them cutting down trees with chainsaws and, even more dangerous, hooking up cut tree trunks so they could be hauled up often steep slopes.

Mechanisation and automation suddenly stopped being nice-to-have, they became must-have, particularly for bigger forestry companies. From 2013 to 2021, the forestry industry went from under 25 percent of production being mechanised to over 65 percent, says Professor Rien Visser from Canterbury University’s School of Forestry, the country’s leading expert in forest engineering.

Whereas a decade ago the average logging operation involved all or the majority of the felling and hooking-up work being done manually, these days the typical forestry crew, at least in big forests, has everyone in a machine. The death toll has started to fall – over each of the past two years three people died. Too many, but better than 10.

But something else happened too: productivity in the forestry sector has gone through the roof.

These days, most crews are harvesting on average 300 tonnes a day, Visser says. A decade ago, 150 tonnes was “a big target”.

Meanwhile, the industry has been able to handle a major expansion, from 20 million cubic metres of wood a year in the early 2010s to 35 million now. And the industry has done that with about the same number of workers, an important factor given increasing labour shortages.

It’s been a slow, painful and very expensive transition. Some of these big machines cost $1-2 million each, a massive outlay for smaller contracting companies that often do the bulk of the work. Some companies went under.

In some hideous way, that unacceptable death toll in 2013 was a tipping point. It forced New Zealand’s forestry companies to do what they should have done anyway, but may not have because of the cost and the risk, because of inertia or union concern about job losses or worries about having to train people to use the new machines.

It forced them to innovate and automate.

The initial move to automation and mechanisation was very challenging, Visser says. “Contractors’ cost structures were much higher, and there was huge pressure to be productive all the time.

“But once you have established a level of automation, no contractor would go back.”

Is Covid an automation tipping point?

And now we have Covid-19 bringing debilitating labour shortages, wage inflation, dramatically reduced immigration and social distancing rules in workplaces. Omicron and maybe future variants are predicted to severely hit workforces, at least temporarily.

But at the same time many sectors – horticulture, manufacturing, IT, finance, construction – are experiencing growth. People want more of our stuff here and overseas.

Which leaves many companies stuck with wanting to produce more to meet demand, but not able to employ more staff to do it.

In the same way unacceptable forestry deaths provided a catalyst to introduce automation in that sector, and the initial Covid lockdown "vaulted us five years forward in consumer and business digital adoption in a matter of around eight weeks”, according to McKinsey Digital, could Covid be the catalyst for wider innovation and a chance to lift New Zealand’s long-running dire productivity figures?

The boring answer is it’s hard to know – yet. Digital adoption is quick and (relatively) cheap; automation is slow and as the forestry industry knows, costs millions.

“History suggests automation takes place faster during recessions and sticks thereafter. It should be doubly true today.” – Daron Acemoglu, MIT

But it seems it's happening overseas. "Covid brings automation to the workplace," says a 2021 article in US emerging technologies magazine Wired.

There are drive-through restaurants using automated voice systems to take orders, there's a meat processing company that introduced automation at the beginning of the pandemic to get around social distancing and has now introduced a camera system that uses AI algorithms to look for foreign objects, such as a stray glove, in freshly cut meat.

“History suggests ‘automation takes place faster during recessions and sticks thereafter,’” says Massachusetts Institute of Technology economist Daron Acemoglu, quoted in the Wired story. “It should be doubly true today.”

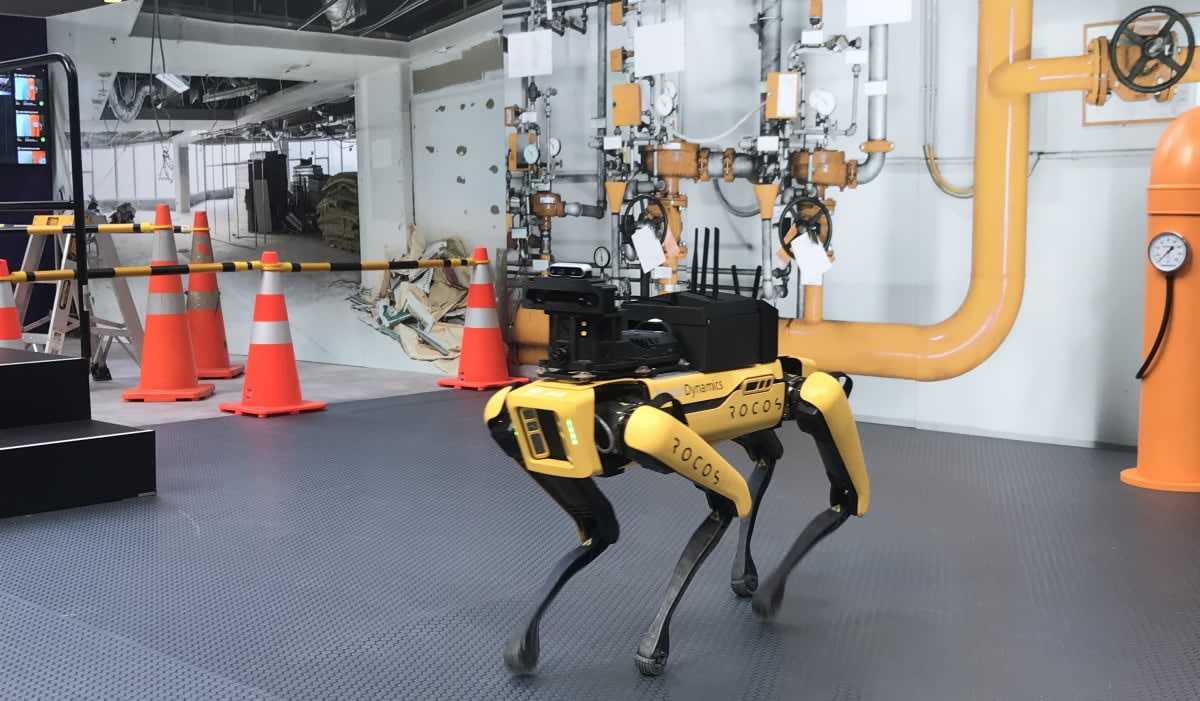

The pandemic has accelerated the adoption of automated systems and robot technology in all sorts of areas – tossing pizza dough, transporting hospital linens, inspecting gauges, and sorting goods, according to US news service AP.

“Robots, after all, can’t get sick or spread disease. Nor do they request time off to handle unexpected childcare emergencies.”

An estimated 29 percent of all current workplace tasks are done by machines. This is expected to grow to 52 percent by 2025 – Deloitte Future of Work report

The article quotes a survey by the nonprofit World Economic Forum that found 43 percent of companies planned to reduce their workforce as a result of new technology.

Since the second quarter of 2020, business investment in equipment has grown 26 percent, more than twice as fast as the overall economy.

Meanwhile, a Future of Work report commissioned by the logistics giant DHL and released in December last year estimated 29 percent of all workplace tasks are done by machines. This is expected to grow to 52 percent by 2025.

A November 2020 survey of executives in 29 countries, including New Zealand, by the business consultancy firm Deloitte found two thirds of business leaders used automation to respond to the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic.

“For years economists have puzzled over the gap between the remarkable power of new technologies and weak productivity growth in the real economy,” Ian Stewart, chief economist at Deloitte UK, said at the time. “Now the pandemic has sparked a surge in technology deployment across the economy. With the right skills to exploit it, this tech surge creates a window for faster economic growth and greater organisational resilience. Very few good things have come from the pandemic – the accelerating adoption of new technologies may prove to be one of the most significant.”

The next Deloitte automation survey is due out later this year.

NZ productivity by the numbers

If Ian Stewart is worried about productivity in the UK, he should see what’s happening in New Zealand.

In a report released in May last year, the NZ Productivity Commission found New Zealanders work on average two hours a week longer than others in the OECD and produce a dramatic 20 percent less value for that work.

A separate report into what the Productivity Commission calls our “frontier firms” – the most productive ones in the economy – gives even more dire results.

The productivity of New Zealand’s frontier firms lags on average up to 45 percent behind that of high-performing small advanced economies, the commission found.

New Zealand has gone from being one of the most productive countries in the world in the late 19th century to being well below average, the economist and Productivity Commission chair Dr Ganesh Nana said.

“No initiatives have had the cut-through to lift New Zealand’s productivity. Working more hours and putting more people into work continues to be the main way that the economy has grown.

“Innovation is the key to unlocking New Zealand’s productivity. There are only so many hours in the day that people can work, so creating new technology and adopting new and better ways of working is critical to achieving effective change.”

A tipping point

That’s happened with adopting digital technology – getting our businesses online. But what about automation?

Brett O’Riley is chief executive of the Employers and Manufacturers Association and co-chair of a business-government-union-Māori initiative, the Advanced Manufacturing Industry Transformation Plan, which aims to boost productivity in the manufacturing sector.

“I think Covid has brought a range of issues into sharp relief because so many have come together,” he says. Labour shortages, inflationary pressure on wages, the global supply chain, the price of land and increased cost of commercial rents particularly in the big cities, the evolution of manufacturing technologies here and overseas, and increased demand for many in the manufacturing sector.

He points to a meme that went around early in the pandemic.

Automation is next, O'Riley says.

“This crisis has forced companies to confront many of these things. I’d be saying ‘Don’t waste a crisis’.”

Picking and packing

Horticulture is perhaps the industry most affected by the dual pulls of growth and labour shortages. So it’s not surprising that’s the sector where there has been huge investment in automation.

The kiwifruit company Seeka is investing $20 million in an automated packline and coolstore near Te Puke which should be operational for this year's kiwifruit season.

The produce company T&G Global is spending $100 million on an automated packhouse, and “millions more” on orchard redevelopment across Hawke's Bay and Nelson.

The company’s latest financial result (the six months to June 2021) saw operating profit almost halved, from $19.5 million to $10.9 million and net profit after tax fall from $9.5 million to $3.4 million. The result was largely because of disrupted shipping and a shortage of workers, its chief executive, Gareth Edgecombe, told shareholders.

Despite its best efforts to attract staff to replace the backpackers and seasonal workers, T&G was still 300 people short every day at the peak of the season, he said.

“This meant we saw an unprecedented amount of unpicked fruit.”

Edgecombe told Newsroom the company has been investing in mechanisation for some years, but “Covid-19 has accelerated this.”

The automated packhouse will be able to pack more than 125 million kilos of apples per season, double present volumes, but with the same number of workers, he says.

Automation is tougher out in the orchard. Winemakers have been picking using machines for years, but grapes are going to get squashed anyway; apples, pears, kiwifruit and stonefruit are fragile and customers don’t buy bruised fruit.

The New Zealand company RoboticsPlus has been working for years on a kiwifruit harvester, and T&G Global had been working with US-based Abundant Robotics to trial their world-first robotic apple harvester, until that company went out of business in July last year.

In the meantime, T&G is working on replacing traditional trees and old orchards with the company’s premium Envy brand planted on 2D structures.

Each platform holds four workers who can pick double the volume. They also make for easier picking, meaning a wider potential pool of pickers, Edgecombe says.

“The new system increases the quality, consistency and yield of fruit and supports the use of automated picking platforms and in time robotic harvesters … With the country’s unemployment rate at an all-time low, together with Covid-related border closures and restrictions, this reinforces we’re on the right pathway to create a highly productive, highly skilled company. But it takes time to transition.”

Beyond horticulture

TMX is an Australian digital supply chain solutions company, which set up an office in New Zealand in September 2020. New Zealand general manager Caleb Nicolson says the company has seen a 40 percent increase in the number of automation enquiries over the past 12 months as companies, including clients looking at automating storage and retrieval systems in their warehouse and distribution centres, look to minimise the number of tasks done by humans.

He says a significant percentage of the cost and time in a manual warehouse is people walking around putting things on, and taking things off shelves. Robots and other automated systems can bring products to people, not the other way around.

“The accessibility of automation means it’s no longer available just to the big guys,” Nicolson says. “You can do it for under $10 million.”

Matt Whitaker, the intelligent automation leader for Deloitte in New Zealand, says a lot of the automation enquiries his team have seen over the past 12-18 months have been for behind-the-scenes systems – “making crazy processes more efficient” and using data more effectively.

Whitaker sees particular demand from companies in the financial services sector, which are seeing growth in demand but finding it hard to get people to handle the new business.

“People want to grow their business but not their headcount. It’s a challenge to get technical and process people in the current market.”

Automation can take hard-to-find staff out of customer and supplier processing tasks such as invoicing and accounts payable, but can also start to use a company’s computer system to give customers the services they want without human intervention, to detect and manage problems customers are facing, and eventually to cross- and up-sell to them.

“It’s exciting when you start using AI to do things smarter at the higher end – leveraging data in organisations, not just to report but to start to predict and take action.

“Once you start to automate those things, you are really going to start to move forward in terms of productivity.”

Ahhh, productivity

Let’s say automation is definitely happening – and outside the horticulture and other high-profile industries much of the information is still anecdotal. When will we see some impact on New Zealand’s grim productivity statistics?

The answer is not for a while.

The latest data, released by Statistics NZ last week and only provisional at this stage, show the numbers only for the year to March 2021, meaning they are almost a year out of date.

They aren’t edifying reading either. Labour productivity – the quantity of goods and services (output) produced per hour of labour – was up 0.5 percent, but only because the fall in the number of people working was greater than the drop in the amount of stuff they produced.

Any impact on productivity of Covid-related investment in technology will probably not come through for a few years, given the way the figures work and the long-term nature of investment decisions, says the Kiwibank economist Mary Jo Vergara.

“There is space for the Government to make it easier, for example with grants being more focused on innovation.”

Investment intentions

Meanwhile, there are notes of caution about whether Covid-19 will be enough of a tipping point to see New Zealand companies adopt automation.

First there is some bad news from the NZ Institute of Economic Research quarterly survey of business optimism reports.

In March 2021, the NZIER survey showed companies were feeling more confident about investment, particularly in plant and machinery.

“Rising labour costs and the reduced ability of firms to bring in workers from overseas given border restrictions has likely sharpened the focus on investment in labour-saving technology,” the survey found.

But that had changed by the end of the year, NZIER principal economist Christina Leung told Newsroom.

“The most recent QSBO showed the manufacturing sector the most downbeat and a decline in investment intentions.

“There is a lot of uncertainty about how Covid will play out and that is making businesses are more cautious.”

It’s a similar message from the ANZ chief economist Sharon Zollner.

While it’s true labour shortages are biting, and there is evidence of some companies investing in automation, there are a number of factors working against investment.

“Distance from market, size of market, rewards for innovation being capped by the size of the market, scaleability being hard, investment dollars being soaked up in improving environmental performance. Some blame the beach, bach culture. And cyclical low interest rates should encourage investment – but now they are going up.”

If spending $1 million on automation brings you a 20 percent productivity boost on a headcount of 200 people, that’s a lot more significant than the same boost with a staff of 20.

“It comes down to expected returns as against risk appetite," Zollner says. "Companies need to be sure demand is going to stay, that competition isn’t going to eat your lunch, and sales are going to hold up.

“Now costs are going through the roof, there’s the uncertainty of Covid – no one is sure when it’s going to hit a pain point, and if households are under pressure how do you know it won’t be your goods they stop buying? Plus, how do you calculate your future real returns when you aren’t sure if inflation is going to be 1 percent or 7 percent?”

Which all makes sense, but the forestry industry expert Rien Visser isn’t convinced by the naysayers.

There is one more cool thing about those expensive machines the forestry contractors bought, Visser says: they didn’t just protect workers, they did a better job.

A critical factor in a forestry company’s profitability is something called value recovery – getting as much of each log up the wood value chain as possible. And it turns out those harvesters and other equipment are pretty good at looking at a tree and working out how to cut it up – mostly quicker and more accurately than their operators.

“Automation and smarts in forestry machinery gives you value, because making a mistake in cutting a log could mean a three-fold difference between highest and lowest value.”

“It’s been worth the effort; it’s a hell of a lot easier,” one contractor says. “There’s no way I’d go back.”