It’s midday in the Wisconsin state capitol in Madison, and that means it’s time for a Solidarity Singalong. A circle of protesters have filled the central rotunda of the venerable building and are singing lustily to the tune of I’ll Fly Away, their voices spiralling up into the dome overhead.

We’re not going away, oh Scotty!

Until the day when justice holds sway.

You might think our mighty cause is lost, but

We’re not going away.

The singers aren’t here just for the harmonies – they really mean it. They aren’t going away. Though their numbers are down to a meagre 15 from the thousands that overran the capitol at the height of Wisconsin’s union battles almost four years ago, they have stuck it out. Every weekday since 11 March 2011, without a break – 1,006 days and counting – they have turned out to sing songs of defiance against the man they call “Scotty”.

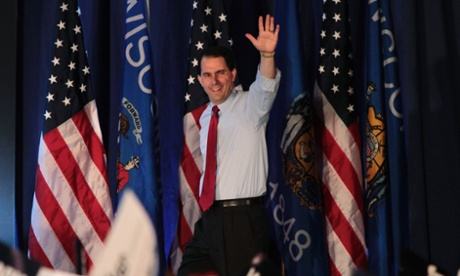

That’s Scott Walker, the governor of Wisconsin. His office is just a few paces from the rotunda and he must surely hear the chorus, though it doesn’t seem to bother him. In his new book, Unintimidated, he recalls protesters chanting at him: “We’re still here!”, to which he gives the dismissive riposte: “Yes, but so am I.”

Having entered the record books in 2012 as the only US governor to survive a recall election, he went on to further confound his opponents by winning re-election last November. That gives him a powerful profile as a fighter and survivor who has won three statewide elections in four years in a purple state that hasn’t voted Republican in a presidential election since it backed his hero, Ronald Reagan, in 1984.

Now Walker is taking that narrative to the national stage. On Friday, he will offer his clearest indication yet of his presidential ambitions when he delivers the keynote speech at the conservative “freedom summit”in Iowa, the state whose caucuses in January will fire the starting gun of the 2016 race for the White House. Then he will travel over the weekend to Palm Springs, California, for that other essential preparation for a Republican presidential candidate: a meeting with wealthy donors – in this case a network assembled by the right-wing billionaire magnates, the Koch brothers.

All these tell-tale signs have got people wondering. As the Republican party begins to search in earnest for a credible candidate to take on as formidable a potential opponent as Hillary Clinton, and with no individual yet fitting the bill – Ted Cruz is too right-wing for the general election, people say; Chris Christie too brusque; Jeb Bush is, well, a Bush; enough already with Mitt Romney! – could Scott Walker be the elusive figure Republicans are looking for?

His close friends believe so. Jim Villa, Walker’s former chief of staff, said that as a fresh face untainted by the machine politics of Washington, he has a strong case to put before his party. “He has a unique opportunity to say that he’s a winner – he’s stood up for conservative principles in his state and repeatedly won.”

Villa told the Guardian that if it came to a national campaign, Walker would woo voters through his personable style. “This guy is the living-room candidate. You meet Scott Walker and you cannot not love him. Even people who don’t like him still think he’s a nice guy.”

Scott Jensen, a former Republican speaker of the Wisconsin assembly who has known Walker since the governor’s student days at Marquette University, agreed that he has likability in spades. “He’s the Eagle Scout and the preacher’s kid – always nice, always polite, the kind of guy you’d like to marry your daughter.”

But Walker is also a disciplined and determined politician who has honed a message that would play well with the Republican party base. “He can project himself as the tough leader who will get the budget in check by making tough decisions that will upset special interests but help working families – that’s where he’s going, and it will sell,” Jensen said.

Determination, however, is only one half the Scott Walker story. The other half is that he is the most polarising politician in modern memory to have occupied the governor’s office in Wisconsin, a state that has arguably become the most polarised in the nation. Exit polls from his most recent victory in November suggest that his support has become almost totally partisan – some 96% of Republican voters sided with him, and just 6% of Democrats.

That is no surprise given the political hurricane he unleashed on Wisconsin just weeks after he was first elected as governor in 2010. When he announced that he planned to strip public-sector unions of their power and make state employees pay some of their pension and healthcare fees, even his own side was taken aback.

“It was so much more sweeping in a purple state than anyone had ever proposed,” said Jensen. “I’m sure to him it was a logical decision, but politics isn’t logical, it’s emotional, and in turn he was surprised by the blowback.”

That blowback included scenes of turmoil at the Capitol as 70,000 protesters flooded the building, as well as the surreal spectacle of 14 Democratic state senators fleeing the state to Illinois in an attempt to avoid a quorum and scupper the bill. Walker calmly sat out the protest, bypassing the senators with a procedural ploy and going ahead regardless.

Exceptionally calm at the centre of the storm

Almost four years later, Madison appears to have regained its equipoise. But you don’t have to look far to find evidence of open wounds and lingering shell shock.

There’s the bunch of protesters who turn up for the daily singalong. “Walker attacked working people on behalf of the wealthy – he hasn’t backed off, why should we?” as one of them, Bill Dunn, put it.

There’s the continuous anger of the public employee unions, whose membership has been decimated since Walker’s anti-collective bargaining bill, Act 10, was made law in June 2011. The teachers’ unions, for example, have lost more than 40,000 members since the changes – almost half their total.

Public schools are struggling with a $900m cut in their annual budget and a further $140m redirected to private schools under the governor’s voucher program. John Matthews, head of the union Madison Teachers Inc, said that the tighter budget had forced schools to increase class sizes, scrap music and art lessons and cancel textbooks.

When asked to respond to Walker’s claim in Unintimidated that his opponents are unable to name a single school that has been hurt by his reforms, Matthews replied: “I could name schools in all 424 school districts that have been harmed.”

In his book, the governor argues that Act 10 freed up tens of millions of dollars to put into classrooms rather than union coffers. “Our reforms were not anti-union,” he writes, “they were pro-student, pro-teacher, and pro-education.”

Peter Barca, the current leader of the Democrats in the state assembly, appears genuinely startled by Walker’s claim. “That’s remarkable he can make that argument, given the actual experience,” he told the Guardian. “Most teachers in the state despise him. They feel they were a target, that he balanced the budget on their backs.”

Barca said that for him, Walker represents something new in Wisconsin conservatism. This was the state, after all, that first gave rise to public-sector unions in 1936 and collective bargaining for government employees in 1959. Politicians from both parties prided themselves in working together.

Then there’s Walker. Barca said the governor reminds him – not by dint of his policies, but because of his tendency to push towards the extreme – of that other Wisconsinite politician, Joe McCarthy. “We’ve never had someone take such far-right positions before, absent McCarthy. It just doesn’t seem to fit.”

And yet, Barca reflected, for the maelstrom he has provoked, Walker has always appeared exceptionally calm at the centre of the storm. “Watching him, he seems insulated from the things that happen around him. I had a colleague who described him as Mr Magoo – the near-sighted cartoon-character who crashes his car, then walks away as if nothing ever happened. Some people see Walker like that – that he just doesn’t feel other people’s pain.”

A candidate not without baggage, however

On Friday in Iowa, Walker is expected to present the image of the steely politician who took the tough decisions needed to rein in Wisconsin’s $3.6bn deficit and create a promised 250,000 new jobs. (He will almost certainly gloss over the fact that Wisconsin still faces a budget hole of about $2bn while only about 100,000 jobs have been created since he took office.) As he writes in Unintimidated: “Today, we can sound like conservatives and act like conservatives – and still win elections. We don’t need to change our principles. We need more courage.” Significantly, he adds: “If we can do it in Wisconsin, we can do it anywhere – even in our nation’s capital.”

Any ambition he might have to carry his Badger State revolution 800 miles to Washington and into the Oval Office is more than mere wishful thinking. Having gone through the hellfires of the recall election, he has built up a sophisticated web of big donor support that is the cornerstone of any modern presidential run. During the recall, major conservative donors rushed to his assistance, helping him raise $37m. Prominent among those was Americans for Prosperity, a conservative mobilisation campaign founded by the Koch brothers, that poured at least $3m and some say as much as $8m into the battle.

The Kochs were the subject, unwittingly, of what Walker calls “one of the worst moments in my life”. At the height of the Act 10 protests, the governor took a call from David Koch – or at least he thought he did, as it turned out to be from a prankster who promptly posted the conversation online. The recording included the governor’s memorable comment that he had “thought about” placing agent provocateur troublemakers among the demonstrators.

Walker insists that he only made the remark to avoid giving offence to the man he thought to be Koch. But that still doesn’t look good.

Neither does the ongoing “John Doe” (that is, confidential) investigation into alleged campaign finance violations during Walker’s 2012 recall fight. Prosecutors have suggested that outside organisations engaged in unlawful coordination to fund the recall campaigns of Walker and other Republicans in breach of state election laws.

Walker has denied any wrongdoing, no charges have been brought, and the investigation has been on hold since last summer following the intervention of a federal judge. “It was a partisan witch-hunt – a classic liberal playbook to smear rising conservative stars,” said Matt Batzel, Wisconsin-based executive director of the conservative group American Majority Action, which supported Walker during the recall.

But the investigation is technically parked rather than dead, and has the potential to rise up again. Should he decide to run in 2016, Walker may find himself exposed to awkward questions under an intense national media spotlight to which he is unaccustomed. It will take all his skills as a communicator to meet the challenge.

‘Don’t underestimate Scott Walker’

Fortunately for him, Walker’s communication skills are widely recognised. He is a past master at conservative talk radio, with a regular seat at the tables of Milwaukee-based hosts Charlie Sykes and Mark Belling, who beam him directly into the homes of the conservative base right across the state. That channel, replicated nationally by the likes of Rush Limbaugh and on television by Fox News’s Sean Hannity and others, could serve him well during the primaries.

“Talk radio helped build Scott’s career, and it has shaped it too. He has a symbiotic relationship with them,” Jensen said.

The governor’s savvy media messaging powers are also acknowledged by his natural adversaries. Nicole Safar, policy director of Planned Parenthood of Wisconsin, has been at the receiving end of some of his sharpest attacks.

As one of his first acts as governor, Walker abolished the state’s $1m in funding for the reproductive health group, which it had used to provide birth control, cancer screening and STD testing and treatment. As a result, five of its rural clinics – serving more than 3,000 patients – were forced to close.

In other moves, he worked with the Republican-controlled legislature to enforce ultrasounds for all women opting for an abortion, ended access to abortion services through state health insurance markets and tried to threaten abortion clinics by insisting they had admitting privileges to local hospitals (a measure blocked by the courts). All these measures chime with his background as the son of an evangelical preacher, whose record in office has shown a consistent opposition not just to abortion but also to some forms of contraception.

And yet when he came to defend his policies during his 2014 re-election campaign, he did so in the mildest of terms. He put out a TV ad in which he said “the decision to end a pregnancy is an agonising one. That’s why I support legislation to increase safety and provide more information to a woman considering her options.”

Safar was amazed, and grudgingly impressed. “He used our very own language against us – turning our arguments to push through his policies that are dangerous to women,” she said. Walker went on to win re-election by 53% to Democratic challenger Mary Burke’s 47%.

For Safar, the lesson has been learned. “He’s a formidable opponent who can present a public face totally at odds with what he’s really doing. Don’t underestimate Scott Walker.”