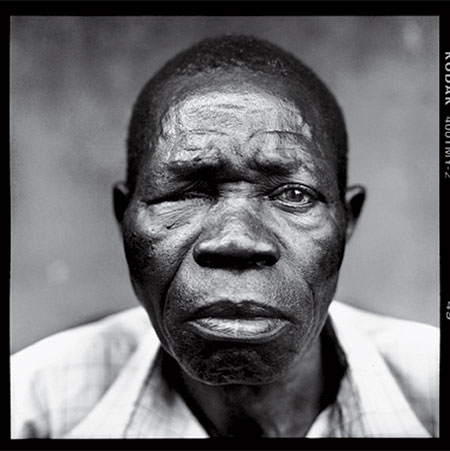

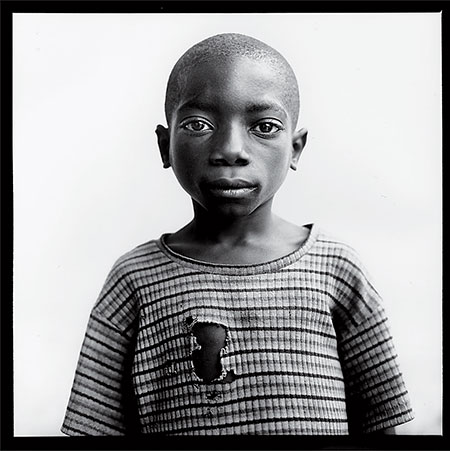

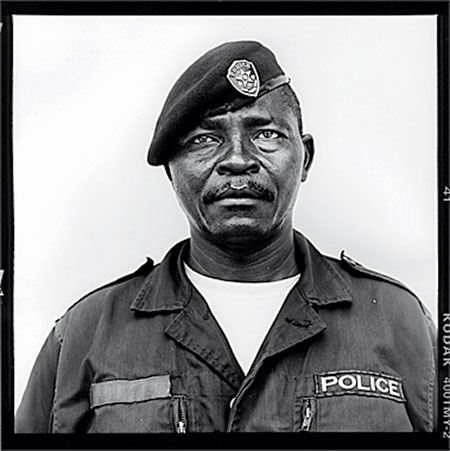

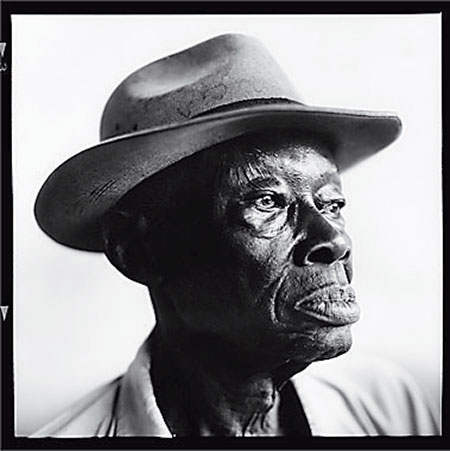

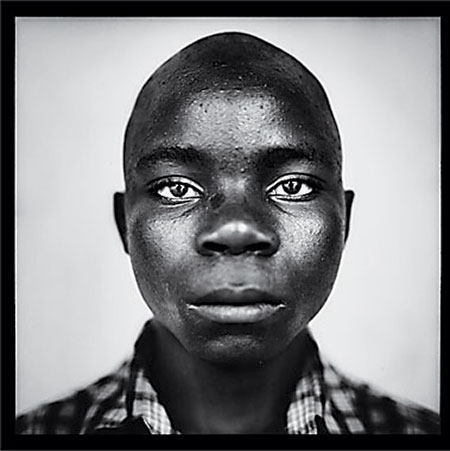

Photograph: Stephan Vanfleteren/Panos Pictures

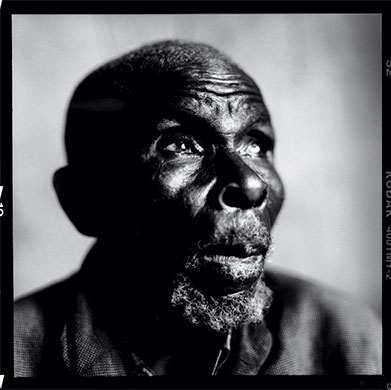

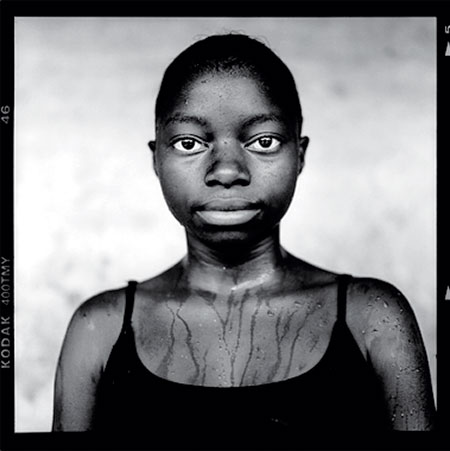

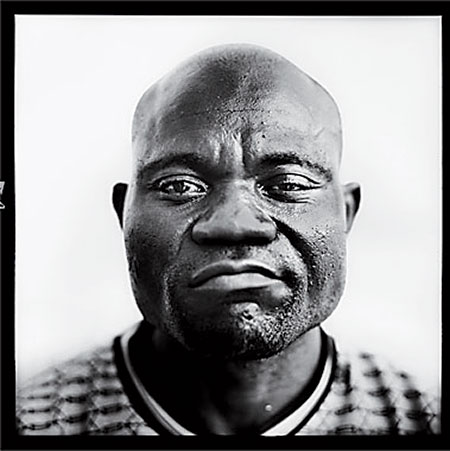

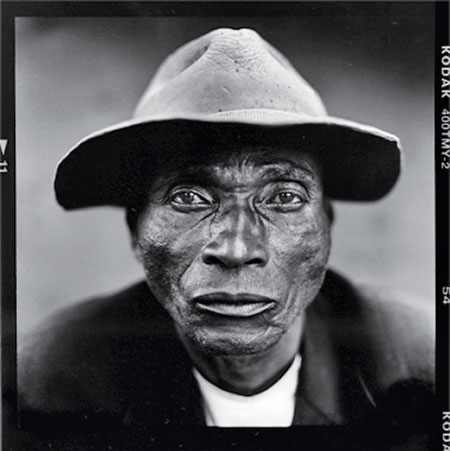

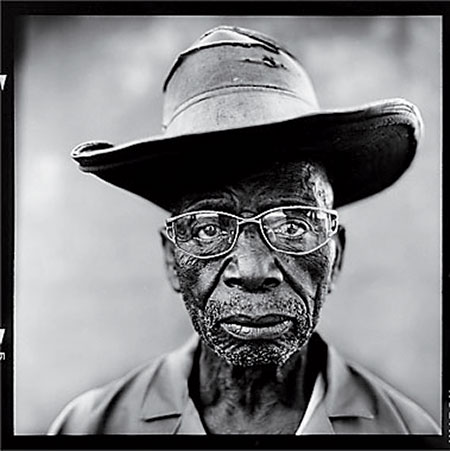

Photograph: Stephan Vanfleteren/Panos Pictures

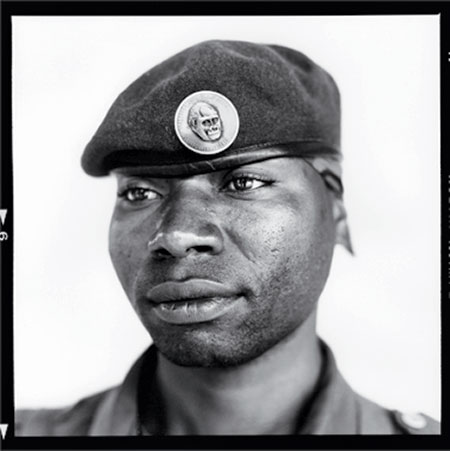

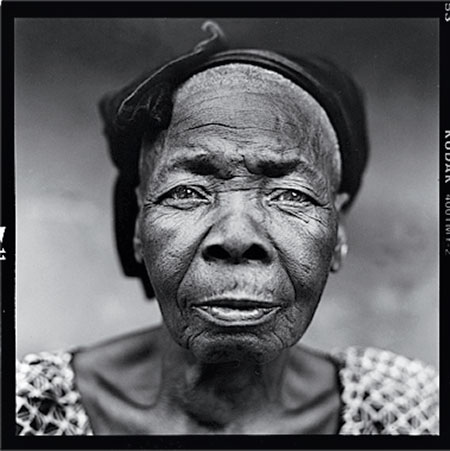

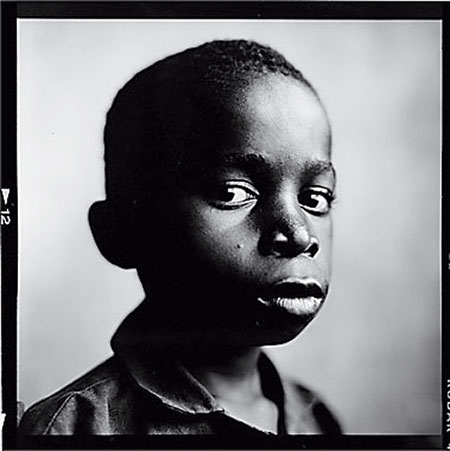

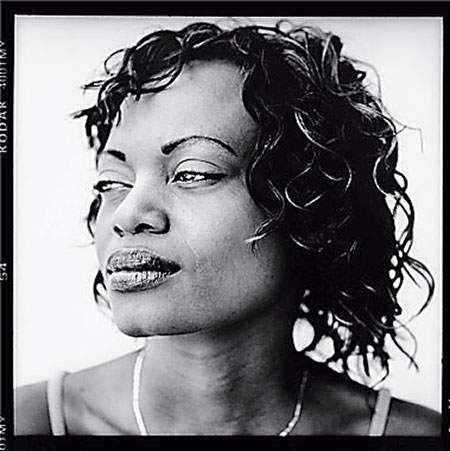

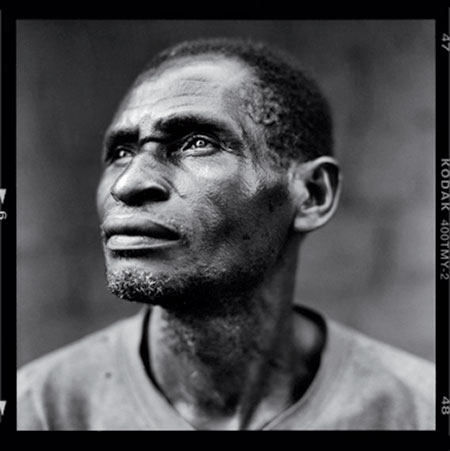

Photograph: Stephan Vanfleteren/Panos Pictures

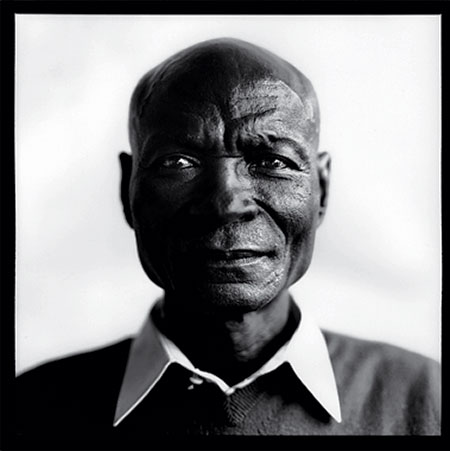

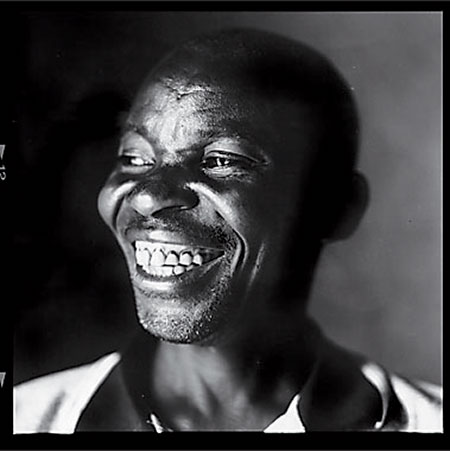

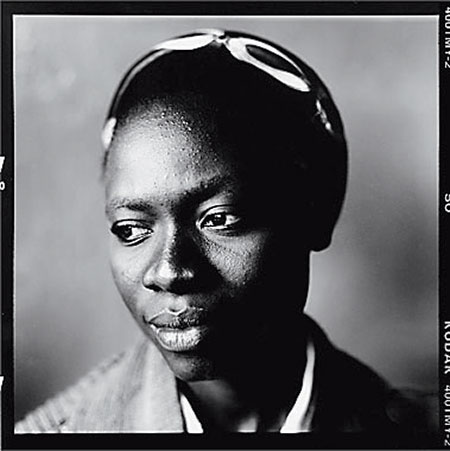

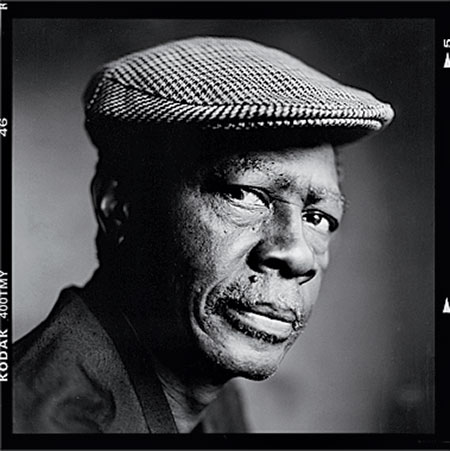

Photograph: Stephan Vanfleteren/Panos Pictures

Photograph: Stephan Vanfleteren/Panos Pictures

Photograph: Stephan Vanfleteren/Panos Pictures

Photograph: Stephan Vanfleteren/Panos Pictures

Photograph: Stephan Vanfleteren/Panos Pictures

Photograph: Stephan Vanfleteren/Panos Pictures

Photograph: Stephan Vanfleteren/Panos Pictures

Photograph: Stephan Vanfleteren/Panos Pictures

Photograph: Stephan Vanfleteren/Panos Pictures

Photograph: Stephan Vanfleteren/Panos Pictures

Photograph: Stephan Vanfleteren/Panos Pictures

Photograph: Stephan Vanfleteren/Panos Pictures

Photograph: Stephan Vanfleteren/Panos Pictures

Photograph: Stephan Vanfleteren/Panos Pictures

Photograph: Stephan Vanfleteren/Panos Pictures

Photograph: Stephan Vanfleteren/Panos Pictures

Photograph: Stephan Vanfleteren/Panos Pictures

Photograph: Stephan Vanfleteren/Panos Pictures

Photograph: Stephan Vanfleteren/Panos Pictures

Photograph: Stephan Vanfleteren/Panos Pictures

Photograph: Stephan Vanfleteren/Panos Pictures

Photograph: Stephan Vanfleteren/Panos Pictures

Photograph: Stephan Vanfleteren/Panos Pictures

Photograph: Stephan Vanfleteren/Panos Pictures

Photograph: Stephan Vanfleteren/Panos Pictures

Photograph: Stephan Vanfleteren/Panos Pictures

Photograph: Stephan Vanfleteren/Panos Pictures

Photograph: Stephan Vanfleteren/Panos Pictures

Photograph: Stephan Vanfleteren/Panos Pictures

Photograph: Stephan Vanfleteren/Panos Pictures

Photograph: Stephan Vanfleteren/Panos Pictures

Photograph: Stephan Vanfleteren/Panos Pictures

Photograph: Stephan Vanfleteren/Panos Pictures

Photograph: Stephan Vanfleteren/Panos Pictures

Photograph: Stephan Vanfleteren/Panos Pictures

Photograph: Stephan Vanfleteren/Panos Pictures

Photograph: Stephan Vanfleteren/Panos Pictures

Photograph: Stephan Vanfleteren/Panos Pictures

Photograph: Stephan Vanfleteren/Panos Pictures

Photograph: Stephan Vanfleteren/Panos Pictures

Photograph: Stephan Vanfleteren/Panos Pictures

Photograph: Stephan Vanfleteren/Panos Pictures

Photograph: Stephan Vanfleteren/Panos Pictures

Photograph: Stephan Vanfleteren/Panos Pictures

Photograph: Stephan Vanfleteren/Panos Pictures

Photograph: Stephan Vanfleteren/Panos Pictures

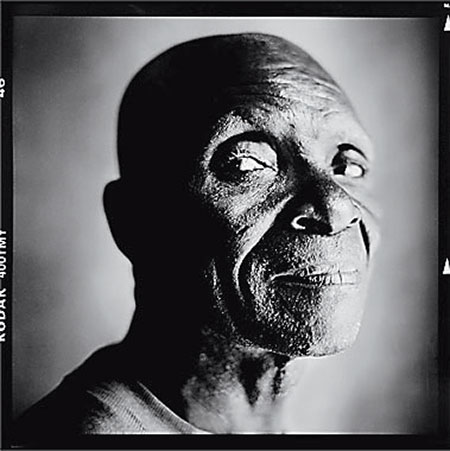

Photograph: Stephan Vanfleteren/PANOS