The world is warming. This fact is most often discussed for the Earth’s surface, where we live. But the climate is also changing from the top of the atmosphere to the bottom of the ocean. And there is a clear fingerprint of humanity’s role in causing these changes through greenhouse gas emissions, primarily from burning fossil fuels.

Over the last several decades, satellites have monitored the Earth and measured how much heat enters and leaves the atmosphere. Over that time, as greenhouse gas concentrations have increased in the atmosphere, there has been less heat escaping to space, causing an imbalance with more heat being retained.

The consequence is a rapidly heating planet.

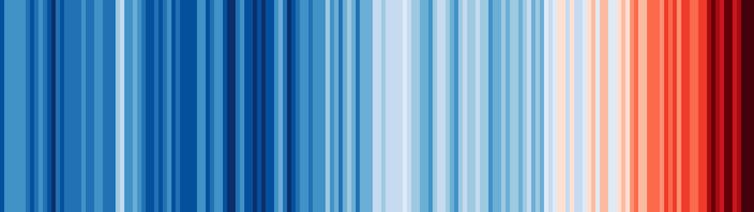

The “warming stripes” are one striking and simple way of visually highlighting the resulting variations in Earth’s surface temperature using shades of blue and red for cool and warm, with one stripe per year.

One billion individual measurements of a thermometer combine to produce the clearest picture of our warming planet from 1850 to 2025. The last 11 years have been the warmest 11 years on record and this sequence is unlikely to end anytime soon.

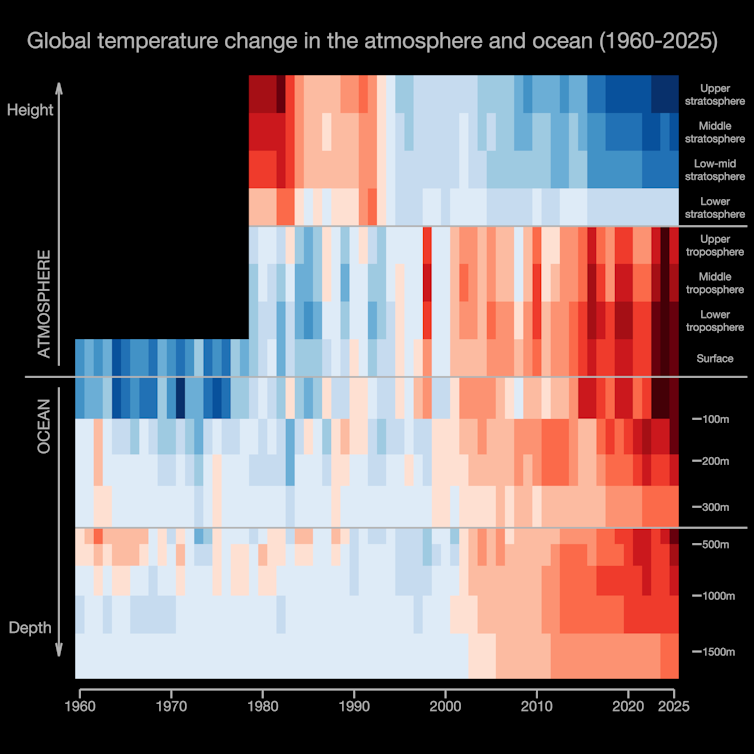

We recently extended this concept upwards through the atmosphere and downwards into the ocean, although the available datasets are shorter.

Satellites have monitored the temperature of different layers of the atmosphere since 1979. The warming stripes for the troposphere (the lowest layers of the atmosphere, within which commercial flights operate) are very similar to the warming stripes of the surface, with the warmest years predominantly occurring over the last decade. Instead of using surface temperature measurements from thermometers, the atmospheric temperature is measured by instruments on satellites called radiometers that detect how much infrared radiation is emitted from air molecules. These satellite-based estimates help corroborate the surface warming that we have already observed.

Higher up in the atmosphere, the picture changes.

The warming stripes over the upper atmosphere (the part called the stratosphere that’s above typical airline cruising height) reveal a cooling trend, with the warmest years around 1980 and the coolest years over the past decade. This feature may appear surprising. If the atmosphere is gaining heat, shouldn’t the stratosphere be warming too?

Actually, this feature is a clear fingerprint of how human activities are the direct cause of our changing climate.

Why is there this pattern of temperature change? The concentrations of greenhouse gases have increased throughout the atmosphere, making the atmosphere more efficient at absorbing and giving off heat. In the lower atmosphere, this effect acts as a blanket, retaining more heat and warming the surface.

Higher up, where the air is thin and very little heat arrives from below, extra carbon dioxide allows the stratosphere to lose more heat to space than it gains, so the stratosphere cools. Another factor is the destruction of stratospheric ozone by substances known as chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), which produces cooling in the lower stratosphere.

This human-caused fingerprint of a warming troposphere and cooling stratosphere was first suggested by scientists as a consequence of increasing atmospheric carbon dioxide levels in the 1960s, long before the cooling stratosphere was observed. Importantly, this pattern would not be seen if, for example, changes in the sun’s brightness were the primary cause of global warming, which instead would lead to warming throughout the atmosphere.

Beneath the surface

Warming stripes for different depth levels in the ocean reveal a broadly similar warming trend as at the surface, with the warmest years occurring over the past decade. The timing of the warming also suggests the heat moves downwards into the ocean from the surface, again consistent with a human influence.

This uptake of heat by the ocean is important, as otherwise there would be a much greater rise in surface air temperature. Globally, the ocean accounts for around 90% of the extra heat stored by the planet. We also see sea levels rising due to sea water getting warmer and expanding, and because land ice is melting and entering the ocean as extra water.

All these observations tell a very clear story. The burning of fossil fuels increases the amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. The physics of why such an increase should warm the surface was understood in the 1850s, before the warming was observed. And the pattern of change observed from the top of the atmosphere to the bottom of the ocean indicates that greenhouse gas emissions are the dominant cause.

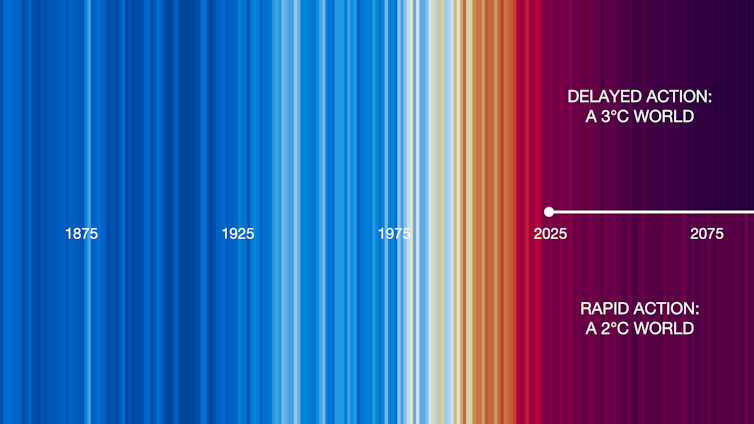

But, what happens next? Because our emissions are causing the climate to change, our collective global choices about future emissions matter.

Rapid action to reduce emissions will stabilise global surface temperatures but delayed action means worse consequences. Which choice will we make?

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 47,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.

Ed Hawkins receives funding from UKRI NERC grants and is supported by the National Centre for Atmospheric Science.

Ric Williams receives funding from UKRI NERC grants and works at University of Liverpool.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.