Shark teeth could lose their cutting edge as oceans become more acidic, new research warns.

Scientists in Germany say rising carbon dioxide levels may erode the very weapons that predators rely on for survival.

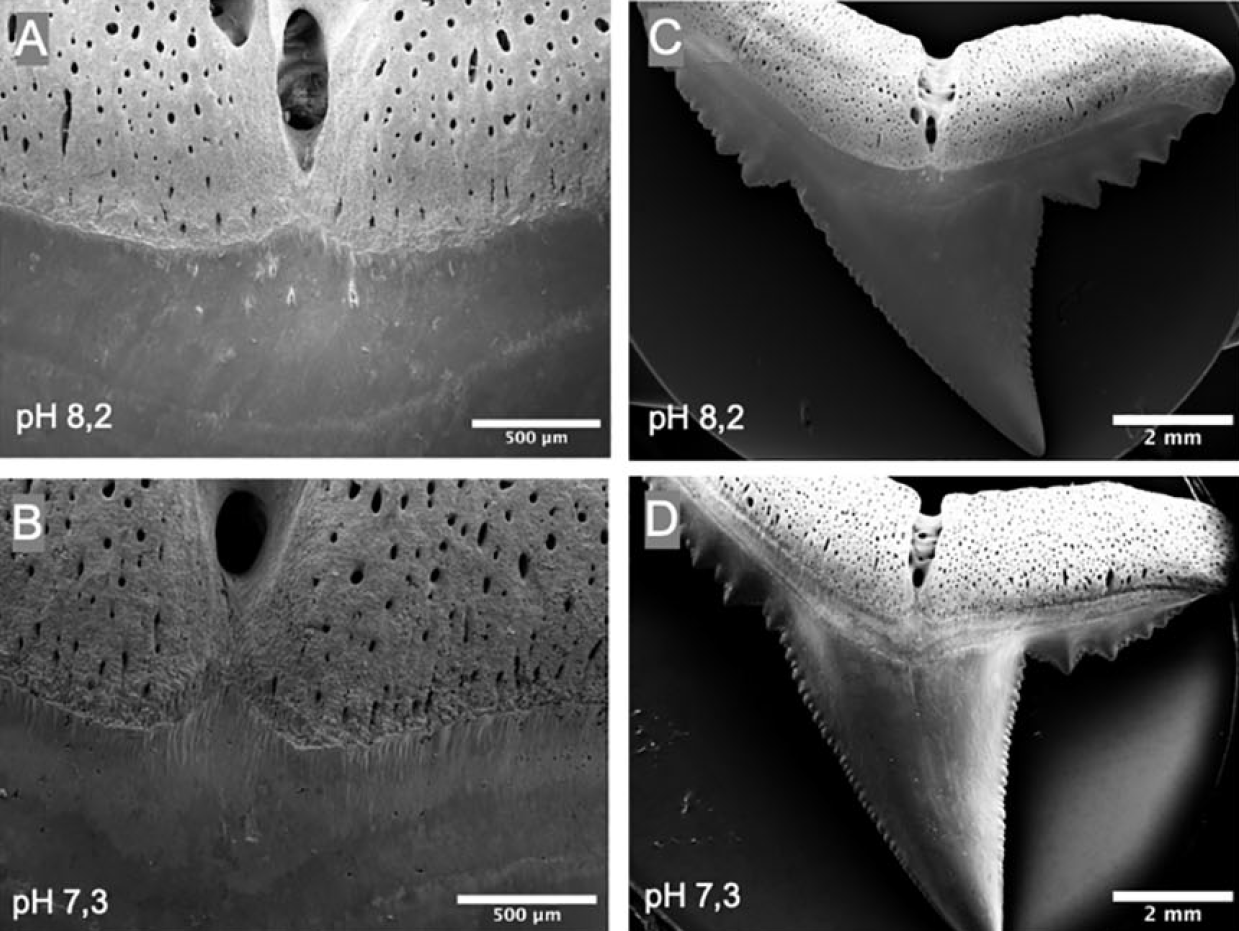

Researchers at Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf incubated discarded teeth from Blacktip reef sharks in tanks of seawater at different pH levels for eight weeks.

At today’s average ocean pH of 8.1, the teeth remained intact but suffered visible surface cracks, holes, root corrosion and structural weakening when exposed to more acidic water reflecting levels scientists expect by the year 2300.

“Shark teeth, despite being composed of highly mineralised phosphates, are still vulnerable to corrosion under future ocean acidification scenarios,” study lead author Maximilian Baum said.

“They are highly developed weapons built for cutting flesh, not resisting ocean acid. Our results show just how vulnerable even nature’s sharpest weapons can be.”

Ocean acidification occurs as the seas absorb carbon dioxide produced by human activities like burning fossil fuels, lowering their pH levels.

The study notes that by 2300, the global average is expected to drop from 8.1 to around 7.3, making the water almost 10 times more acidic than it is today.

Acidification is known to weaken corals, dissolve the shells of molluscs like oysters and mussels, and interfere with the ability of crustaceans such as crabs and lobsters to form exoskeletons.

Some studies suggest that juvenile fish lose their ability to detect predators in more acidic water.

Researchers argue that while sharks are famed for their ability to shed and regrow teeth, microscopic damage from acidifying seas may still pose long-term risks by altering their hunting efficiency.

If acidification compromises their ability to bite effectively, it could make it harder for sharks to catch fast or tough prey.

While they can replace teeth, doing so more often or under harsher conditions could cost energy that might otherwise go into growth or reproduction.

Professor Sebastian Fraune, senior study author who leads the university’s Zoology and Organismic Interactions Institute, said the findings emerged from a bachelor’s project that grew into a peer-reviewed study. “Curiosity and initiative can spark real scientific discovery,” he said.

The work only tested non-living teeth, meaning possible repair or replacement processes in living sharks were not captured. Even so, the results highlight how ocean chemistry changes can ripple through marine food webs.

“Maintaining ocean pH near the current average of 8.1 could be critical for the physical integrity of predators’ tools,” Mr Baum said.

Many shark species are already in decline. According to the IUCN Red List, more than one-third of sharks and rays are threatened with extinction, largely due to overfishing, bycatch, and habitat loss.

Sharks are apex predators and play a crucial role in keeping marine ecosystems balanced. By regulating prey populations, they maintain the health of seagrass beds and coral reefs, which in turn support biodiversity.

Three killed in Vietnam as Typhoon Kajiki brings floods and blackouts

Heatwaves are making people age faster, study warns

Can osmosis power the future? Japan launches Asia’s first plant

Typhoon Kajiki makes landfall in Vietnam as authorities close schools and airports

China races to build world’s largest solar farm to hit emission goals