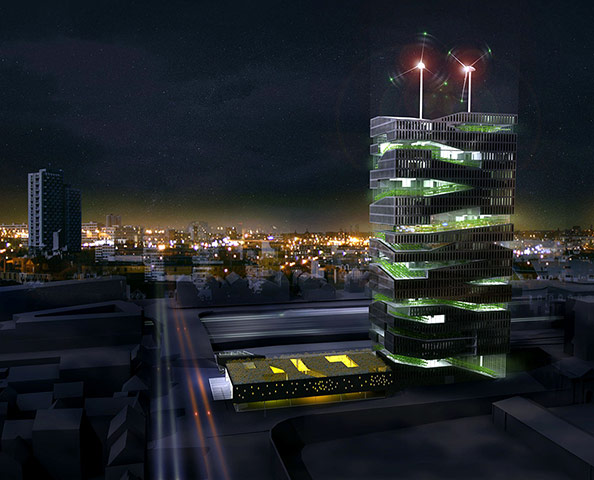

Current estimates suggest that by 2050 the world will be inhabited by 9 billion people, 80% of whom will live in cities. To some extent, urban farming will have to happen. But, if done smartly, it could revolutionise the way we view food production and create a local food movement for the urbanite. Mixed-use skyscrapers are the perfect example of a smart city concept, putting those tall, glass buildings to good use as greenhouses. But at ground level too, mixed-use parks and urban orchards could begin to provide food to the masses. Think it couldn't happen? It already did. During World War II, the Dig for Victory campaign saw formal gardens and parks turned into allotments, producing millions of tonnes of food and, effectively, defeating German blockades. Photograph: Rex Features/QKD

Lampposts are not only the most visible element of the smart city, but potentially one of the most effective. Already connected to the electric grid and spanning the length and breadth of any urban area, they run like veins through a city. Replacing current bulbs with LED lighting could, according to Cisco, reduce a city's lighting bill by 80%. Further savings could be made by using sensors that detect whether people are on the street, turning the light off when it's not needed. But lampposts can do much more than simply light the streets. Barcelona is trialling sensors on lampposts that will monitor C02 emissions and noise levels, while other cities are laying broadband cables alongside electric cables, making lampposts effective Wi-Fi hubs. It's all a long way removed from the gas lamp. Photograph: Erik Von Weber/Stone

Making an existing city “smart” requires a rethink of its transport system. Few cities have the money for major undertakings such as London's Crossrail project, currently slicing through the UK capital at great expense. But, arguably, that isn't a “smart” solution – merely an incremental improvement. Glasgow, winner of the Technology Strategy Board's Future Cities Demonstrator competition, hopes to reduce urban transport by better understanding its current use, using data to highlight duplication and ineffeciency in everything from local bus use to social care mini buses. In Barcelona, meanwhile, they are looking to replace the spaghetti-like bus map with a simple grid system running north-south and east-west. Any journey will be possible by making only one change, it is easier to understand, and it will require fewer buses. Oh, and the buses will be electric.

Photograph: Alamy

Modern city infrastructure is increasingly mixed-use. The Olympic Park development, for example, not only gave London new sports stadiums, but also created the biggest urban park in Europe for 150 years, a new university, allotment space and affordable housing. The best example currently in construction, however, combines two smart city necessities: mixed-use building and renewable urban energy generation. And then there's waste recycling and recreation too. By 2016 a 100-metre-tall incinerator in the heart of Copenhagen will be generating energy by burning urban waste, while its sloped roof functions as a park in summer and a ski slope in winter. Photograph: Buda Mendes/STF/LatinContent WO

A smart city cannot truly be a smart city without an integrated operations centre. The enabler of smart cities is that we now live in a world of multiple sources of data. Computers and sensors can tell us how people use cities, the efficiency of transport systems, and where and when energy is used. That information would once have been collated by a person with a clipboard stopping people on the street. But now that the information is produced digitally, it can be collated. This is where the integrated operations centre comes in: lots of people, lots of screens and lots of information feeds, collating and utilising information to design more efficient systems. It is the beating heart of a smart city. Photograph: Mario Tama/Getty Images North America

Did you think a bin was just for throwing stuff away in? Wrong. In London's Square Mile there are already more than 100 “smart bins”. As well as being a receptacle for recycling, they feature digital screens broadcasting a live channel of breaking headline news and live traffic information. They can also communicate directly with mobile devices through Wi-Fi and Bluetooth technology. And they're bombproof. The jury's out on whether it's a temporary gimmick or here to stay, but one thing it proves is that “mixed use” isn't a concept restricted to buildings. Even the most humble objects of urban infrastructure will need to do more than one job in the smart city. Photograph: Dan Kitwood/Getty Images Europe

Phone boxes are a ubiquitous feature of any town. In London, tourists pose for photographs beside Sir Giles Gilbert Scott's famous red design. The trouble is, no one uses them to make phone calls any more. Any other extraneous urban object would simply be removed, but the telephone box has one advantage: it is wired up to the grid. Smart cities require multiple public grid connections, and telephone boxes provide just that. New York recently held a Reinvent Payphones design challenge. The winners, announced in March, included: a touchscreen information hub and charging station; a voice-controlled pillar offer digital signage; and a weather station and environmental monitor. Photograph: BORIS HORVAT/AFP

The greatest leap forward in smart technology has nothing to do with town planning or urban design. Rather, it is the smartphone. Courtesy of Messrs Apple, BlackBerry, Samsung et al, we now hold computers in our pockets far more powerful than the desktops we had 10 years ago. With GPS technology and map apps, they have the dual benefit of allowing us to navigate the city with ease, and providing data for city and transport planners to better understand how we are using the city. But even more potent is the potential of apps that allow users to share location information with each other, recommend shops and restaurants, plan cycle routes, set-up community schemes or even interact directly with a city's integrated operations centre. This could see smart citizens running smart cities in a much more informed and democratic way than the top-down city authorities of old.

Photograph: Future Publishing

The major modern transport innovation of smart cities is nothing as flashy as new train or tram systems. The bicycle is king. Already offering a clean and healthy form of transport, making it safe is the final piece in the puzzle. And that requires cycle-only lanes. While London Mayor Boris Johnson might talk a good “'cycle superhighway”, other cities have actually gone ahead and done it. Copenhagen has been prioritising cycling since the early 1990s, establishing a city-wide cycling network. The share of people commuting by car fell from 42% in 1996 to only 26% in 2004, whereas 36% now commute by bicycle. In 2008, Greater Bristol was chosen as England's first “cycling city” and received £11m from the Department for Transport to transform cycling in the city and introduce cycle-only lanes. Any municipality with “smart city” ambitions must do the same. Electric bikes are soon to follow.

Photograph: Franck Guiziou/Hemis.fr RM

Knocking down the heritage of a city and building anew is rarely a popular choice. So retrofitting and finding new uses for old buildings is a firmly held smart city principle. New York has made one of the most visible moves in this direction with the High Line park, showing that an old municipal railway line can reintroduce green space into the city centre. London's Tate Modern, too, transformed an old power station into an art gallery with spectacular success. Retrofitting buildings still in use, however, may be more important. To help hit its ambitious energy and water consumption reduction targets of 70% and 30% by 2030, Sydney is retrofitting 44 major buildings. Old on the outside, new on the inside – and ideally incorporating an element of micro-power generation on-top – they could become the defining symbol of a smart city.

Photograph: National Geographic Creative