In the 1960s and 70s, the youth of the United Kingdom, the United States and Australia rebelled by protesting against the Vietnam War, trying psychedelic drugs, embracing free love and discovering the Beatles. Meanwhile, what their contemporaries in China were getting up to was just as transformative.

The key difference, as Linda Jaivin’s book shows, is that the young Chinese rebels’ actions had profoundly destructive consequences – and their senseless behaviour was masterminded by their “great leader”, Mao Zedong.

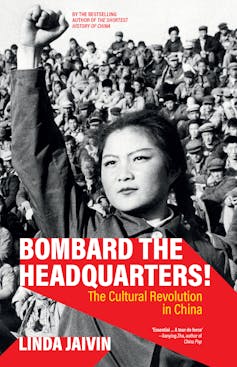

Review: Bombard the Headquarters! The Cultural Revolution in China – Linda Jaivin (Black Inc.)

Bombard the Headquarters! is a compelling but disturbing account of what happened in China during the Cultural Revolution. In just over 100 pages, alternating between broad brush strokes and a fine-grained touch, Jaivin’s book takes the reader on a tumultuous journey through the political upheavals in China from 1966 to 1976.

She is a consummate storyteller. This, when combined with an intimate knowledge of Chinese language and a solid grounding in existing scholarship on China, equips her well for the mammoth challenge of making sense of the most indelible national trauma of 20th-century China.

A new revolution

The book starts with the years 1949–66, giving readers a taste of how Mao, motivated by political neurosis, set out to foment a new revolution.

Having established the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1949, he became increasingly worried about the “capitalist, feudalist and revisionist” elements he believed had infiltrated the PRC government and Chinese society. He wanted to ensure China did not stray from its socialist values. But he also wanted to remove his detractors from the Party ranks and reassert his authority.

So he encouraged Chinese youth to take part in the struggle against the “capitalists” and “bourgeois”. This led to the emergence, in 1966, of a number of cultural and social practices that later came to be uniquely associated with the Cultural Revolution.

One was the Red Guard. Primarily high school and university students, these militant young people played a key role in carrying out Mao’s mission to eliminate the perceived enemies of socialism and uphold proletarian ideology of class struggle, anti-intellectualism, and the need for permanent revolution. The Red Guards attacked intellectuals, destroyed cultural artefacts and persecuted “counter-revolutionaries” who held “bourgeois” values such as individualism and cultural elitism.

The Red Guards, workers and other rebel groups were prolific producers of dazibao, or “big-character posters”. These posters were often written to denounce teachers, officials or anyone seen as opposing Mao Zedong’s revolutionary ideals.

Another social phenomenon was chuanlian: the widespread travel of Red Guards across China to exchange revolutionary ideas and spread Maoist propaganda. Endorsed by Mao himself, millions of young people used free train passes and government support to visit Red Guard groups in other major cities.

Chuanlian led to widespread disorder, the disruption of transport systems and the escalation of violent confrontations between rival Red Guard factions.

Epic drama

The years 1967–69 witnessed the most violent and chaotic phase of the Cultural Revolution. The movement spread from universities and the cultural realm to factories, rural areas and the public service sector in local governments.

Jaivin takes readers to Shanghai, Wuhan, Inner Mongolia – and then back to the campus of Tsinghua University in Beijing. We learn that public humiliation, beatings, torture and forced confessions were common.

Many people were imprisoned without trial, or were even driven to suicide. Violent clashes also occurred between rival Red Guard factions and later between civilians and the military, leading to the deaths of hundreds of thousands, possibly millions of people.

The following period, 1970–76, saw a number of transformative events, including the deaths of Premier Zhou Enlai in January 1976 and then Mao in September.

In 1971, Lin Biao suddenly exited the Chinese leadership. A close ally of Mao during the early years, Lin later rose to become his designated successor. In 1971, however, Mao grew suspicious of Lin’s ambition. Lin fell from power under mysterious circumstances, after allegedly plotting a coup. He died in a plane crash in Mongolia while reportedly fleeing China, and the Chinese government later denounced him as a traitor.

Another turning point involved a curious encounter between some Chinese and American ping-pong players in 1971. This encounter led to the well-known ping-pong diplomacy that eventuated in the normalisation of US–China relations, as marked by President Richard Nixon’s visit to China in 1972.

In 1976, the Tangshan Earthquake, considered one of the worst natural disasters in recorded history, killed half of that city.

With an innate sense of the dramatic, Jaivin conjures up these historical moments like a scriptwriter for an epic historical film.

Radioactive memories

The Cultural Revolution officially ended with the 1976 arrest of the “Gang of Four”. This is a group of four political figures – one of them Jiang Qing, Mao’s wife – who were closely aligned with Mao, and played a key role in promoting his ultra-leftist radical politics. But it has cast a long shadow.

In the final pages of the book, Jaivin offers her summary of the Cultural Revolution this way:

It was supposed to imbue the nation with such a strong ethos of egalitarianism and self-sacrifice that corruption, bureaucratism and ‘bourgeois tendencies’ would forever be banished from China. Instead, it has become a cautionary tale that cannot be told, a radioactive memory and a source of multi-generational trauma.

And her assessment of Mao, the instigator of the Cultural Revolution, is equally concise:

A complex, contradictory and often cantankerous figure, larger than life and all too human in his flaws, Mao was capable of the grandest revolutionary visions but also the pettiest manipulations. He was both an inspirational leader and a remorseless tyrant.

New life to a sorry period

One benchmark for the success of a short book on a “devilishly complex” topic is whether readers are left wanting to know more. Measured against this benchmark, Jaivin has certainly succeeded. For this reader, the book provokes many questions.

What was the psychology behind the mass hysteria of the Red Guards, and what led them to commit acts of violence that call to mind what Hannah Arendt dubbed “the banality of evil”? What lessons can we learn about the dangers of personality cults and the worship of authoritarian dictators – which, in the case of Mao and numerous others throughout history, has enabled a single strong man (most often it is a man) to consolidate authority, suppress opposition and legitimise his dominance for many years?

Another benchmark for the success of a book dealing with collective traumas with lasting impacts is whether readers can still enjoy reading the book, without being overwhelmed by its seriousness.

Jaivin by no means makes light of the massive scale of violence, death and human suffering inflicted by the Cultural Revolution. But she approaches her topic as an epic tale featuring Mao as the central figure, with a big cast of characters including party leaders, the Gang of Four, the Red Guards and rebels, and prominent victims.

The human drama of the power struggles and power plays involving these characters is gripping and disturbing in equal measure. Jaivin had a gift for keeping her readers engaged.

The book will appeal to a number of different readerships. For those in the Chinese diaspora who experienced the Cultural Revolution firsthand, it is a chance to relive the nightmare, but in the comfort of knowing it is now firmly in the past – as long we remain alert to the risk of history repeating itself.

For non-Chinese readers, Jaivin’s narrative flair and sense of drama gives new life to what is almost certainly the sorriest period in recent Chinese history.

Wanning Sun does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.