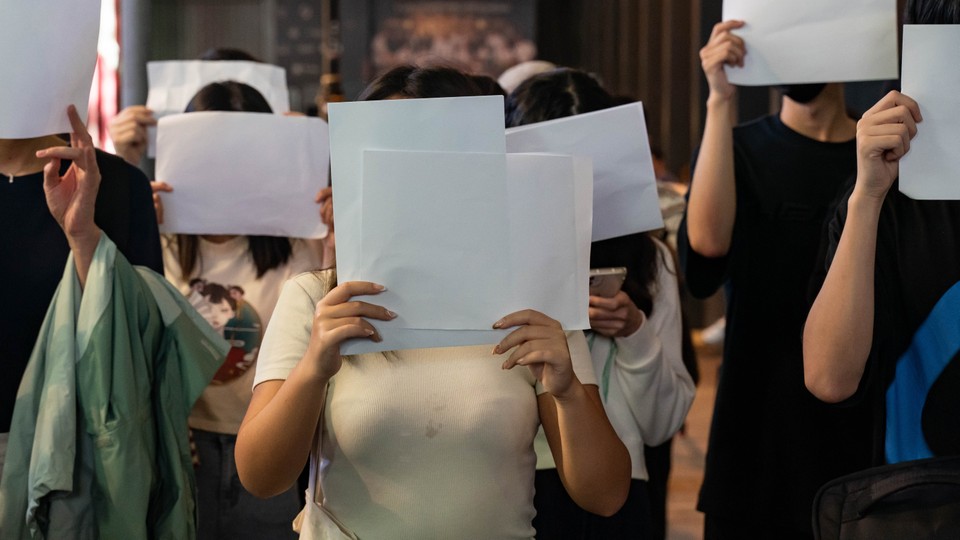

The A4 Revolution that erupted in China in the past week is not really a revolution at all, not yet at least. The term revolution implies a sustained movement aimed at overthrowing the Chinese Communist Party. At this stage, the A4 Revolution—named after the size of the printer paper held up at vigils throughout the country—is a series of scattered, spontaneous protests against the brutality and absurdity of “dynamic zero-COVID” lockdowns and quarantines. The blank sheets say nothing and everything at the same time.

These protests do not need to topple the regime to have long-term consequences. As an academic researcher, I have interviewed Chinese dissidents, many of whom fled China during Xi Jinping’s rule, about their life stories. Many of them described a moment of political awakening, when they learned something firsthand about the party’s grim brutality that they simply could not forget.

For some, that moment was an experience with censorship; for others, it involved a brush with corruption or state repression. They then chose to voice their true feelings about democracy, freedom, and politics in China, knowing full well that they would suffer harsh consequences. The pain of keeping those feelings inside exceeded their fear of what the state could do to them. They made a conscious decision to “live in truth,” in the words of Václav Havel, the Czech dissident turned president. My dissident interviewees tended to view that moment in their lives as cathartic, a psychological liberation that could not be denied or reversed.

The protests of this week may stir that sense of political consciousness among their participants, and maybe among bystanders as well.

Most outside observers might not grasp just how brutal and absurd China’s COVID policies have become. Lower-level officials, eager to demonstrate zeal for Xi Jinping’s “people’s war” on the virus, routinely violate basic human rights, turning citizens’ homes and apartments into temporary prisons, with barricades and all. The past few months have seen the accumulation of preventable tragedies, many of which have gone viral on Chinese social media. In September, 27 people in Guizhou died in a bus accident while on their way to a quarantine facility. In late October, a 14-year-old girl in Ruzhou died in quarantine, apparently after being refused timely medical care. A few weeks later, a 3-year-old boy died after a suspected gas leak at a locked-down residential compound in Gansu province. COVID-control workers prevented the boy’s father from leaving the compound in time to get him medical treatment.

After at least 10 people under COVID lockdown died in an apartment fire in Urumqi, Xinjiang, the region that is home to China’s repressed Uyghur Muslim population, thousands of Chinese citizens suddenly decided to “live in truth.” They are not activists by trade, just normal people, innovating and improvising in the moment. Many of them are students, sons and daughters of the Tiananmen generation, who had themselves protested on campuses and in the streets 30 years before. And like the Tiananmen moment, the A4 Revolution reflects an unlikely solidarity across groups—Uyghur and Han, workers and students, citizens in the mainland, Hong Kong, and overseas. Whatever social contract can be said to exist between Chinese citizens and their government has fundamentally changed.

On Wednesday, word spread that Jiang Zemin, a former general secretary of the party, had died at age 96. Jiang Zemin was no democrat, and he came to power after the Tiananmen Square crackdown in large part because of his reputation as a reliable hard-liner. But his tenure was ultimately defined by a continued commitment to what Deng Xiaoping, the architect of the country’s market-oriented economic policies, called “reform and opening up.” Under his watch, life improved dramatically for many Chinese citizens. He was also famously more charismatic and approachable than other Chinese leaders—he enjoyed quipping with journalists and foreign leaders, and singing and speaking in a number of languages.

When a previous leader dies, this provides the population with a “focal event”—an opportunity to spontaneously act together and express a point of view. Mourning a fallen leader can be a way to indirectly criticize the current leader. This happened in 1989: The death of the reformer Hu Yaobang was what brought students to Tiananmen Square in the first place. Jiang’s death could not have come at a more sensitive time for Xi’s regime, and the funeral will be a tightly managed affair. Flowers and candles will join paper as dangerous symbols of contention.

The Communist Party has quite literally been preparing for mass mobilization for decades, and the regime’s sizable and significant repressive apparatus is already kicking into gear. The playbook will be to physically impede protests, to round up and intimidate ringleaders, and to heighten censorship by threatening people for social-media activity. Students will be sent home for break early. And if things escalate further, the regime has darker tools still: branding protests as influenced by “hostile foreign forces,” using plainclothes police and “thugs for hire” to beat people, or perhaps enforcing lockdowns and quarantines to dampen activism. Anyone looking for the protests to produce regime change or meaningful political reform in the near term will likely be disappointed. But that is the wrong way to evaluate these events.

The Democracy Wall movement of 1978 allowed Deng Xiaoping to gain the upper hand in the succession battle after Mao Zedong’s death. Deng’s victory in turn led to economic and political reform and to China’s economic miracle. The Tiananmen Square movement, though brutally suppressed, ultimately led the party to invest more in public goods and participatory channels such as the People’s Congress system. The A4 Revolution may be the force that pushes China out of Xi’s tight grip and empowers more moderate thinkers at elite levels in the party.

But even if it does not, it will have empowered the Chinese people. The “Chinese people have stood up,” as Mao once put it. They will likely be pushed down again. But these moments of temporary dignity can produce political change downstream in ways that are difficult to predict and discern at first glance.