Women dancing in swirling costumes, musicians, food vendors and even a former prime minister battled to generate a festive atmosphere at an event marking the 50th anniversary of ties between Japan and China, held in a rain-sodden Tokyo park last Saturday.

The low-key celebrations symbolize the renewed frictions between Asia’s biggest economies, which face growing geopolitical barriers to restoring friendly ties -- or even just stabilizing relations. Neither leader was scheduled to attend events on Thursday commemorating the anniversary of the normalization of relations in 1972.

That’s partly a function of worsening ties between China and the US, Japan’s only formal military ally. The two are sparring over a range of issues, none more dangerous than the status of the self-governing island of Taiwan. Beijing sees the island as part of its territory, while US President Joe Biden has vowed to defend it against invasion.

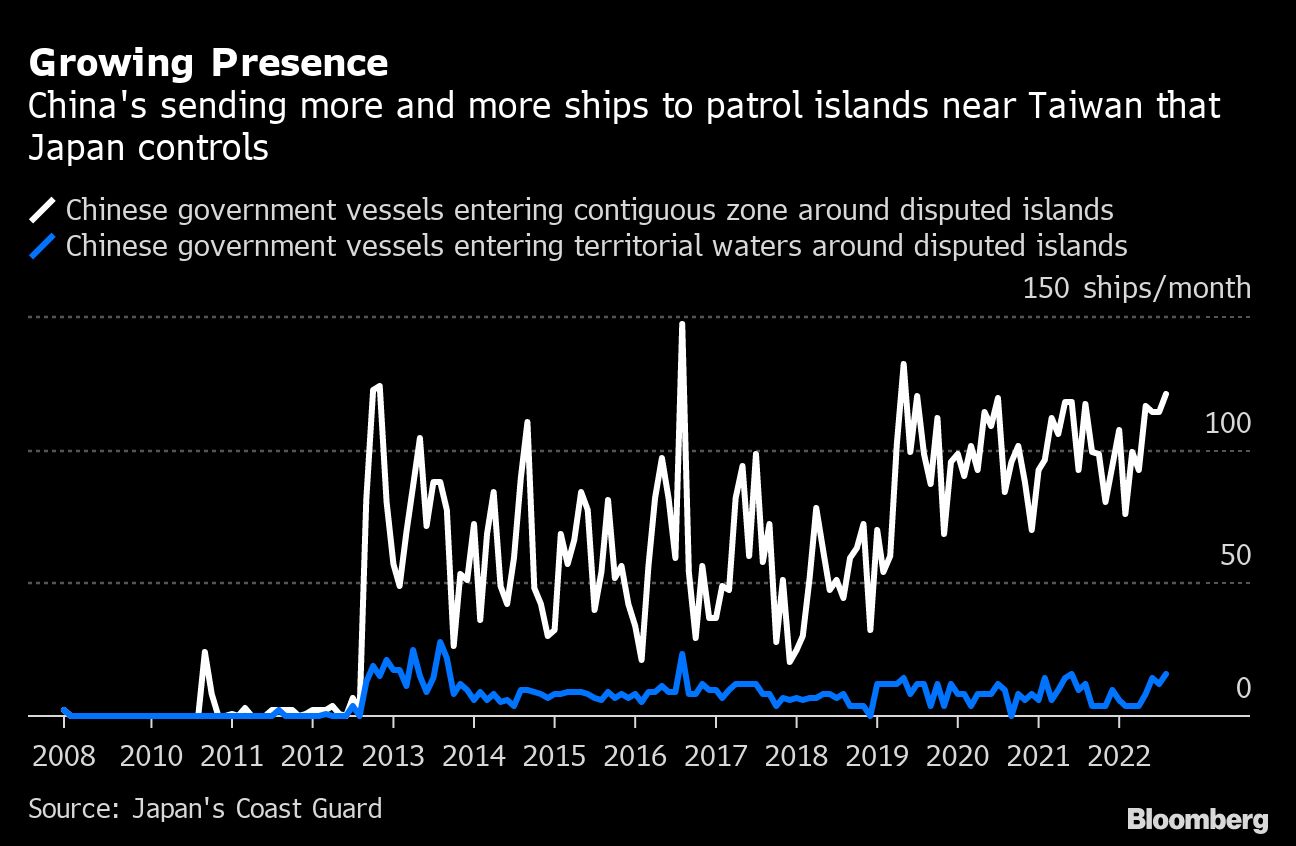

Japan has also been increasingly vocal about the importance of Taiwan to its own security. Chinese military drills around the island last month involved lobbing missiles into waters close to Japan, and ships from both countries continue to chase one another around disputed territory in the East China Sea.

While tensions between Japan and China still aren’t as high as a decade ago, the divisions between them now appear to be growing more permanent and structural. Leaders from the nations are barely talking: A year after taking office Prime Minister Fumio Kishida is yet to hold a summit with Chinese President Xi Jinping, and their foreign ministers have only met once virtually. China canceled a planned meeting between them last month over Taiwan.

“Japan is still attempting to carve out a position in which it engages China while supporting the US-led order, but this is becoming harder and harder,” said Amy King, associate professor in the Strategic and Defence Studies Center at The Australian National University. “Japan’s selective engagement of China has become a lot more difficult for Japan to manage in recent years, as US-China relations have worsened.”

Long practiced at threading the needle between the two giant powers, Tokyo is facing increasing pressure to pick a side. For its part, China has drawn closer to Russia, taking part in joint military exercises near Japan and picking a central Asian forum attended by President Vladimir Putin as the venue for Xi’s first trip outside China in two years.

Years of effort by the late Prime Minister Shinzo Abe helped revive ties, which had reached their lowest postwar point when he took over in 2012 amid a flare-up of the dispute over who owns the disputed islands. Relations improved enough to allow preparations to begin for a 2020 state visit by Xi.

However, Abe’s successors, Yoshihide Suga and Kishida, have had less room to bridge the gap in an increasingly bifurcated world, where the US is urging its allies to shift their supply chains away from China. They responded by shoring up ties with the US and other democracies, and shifting toward the US on issues like Uyghur human rights. Kishida has stepped up ties with NATO, as well as strengthening the Quad, the security dialogue that includes Australia, India, and the US.

“In the last two years, the Japanese government began to collaborate with the US to promote a kind of decoupling between the US and China,” said Yuichi Hosoya, a professor of international politics at Keio University in Tokyo. “The current situation shows much more structural confrontation between the liberal democracies and authoritarian regimes.”

Perhaps most painfully of all for China, once circumspect Japanese officials have become increasingly outspoken on Taiwan. Shocked by Beijing’s 2020 clampdown on Hong Kong, and all-too conscious of the narrow waters separating Taiwan from its own vulnerable southwestern islands, Tokyo’s politicians have emphasized the direct link between Taipei’s security and that of Japan.

Last year Biden and Suga referred to the issue in a joint leaders’ statement for the first time since 1969, sparking a protest from China. Tensions soared with US House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan in August this year, which was met with China’s biggest live-fire drills around the island in decades, including missiles that landed close to Japanese territory. Kishida implicitly backed Pelosi’s trip by inviting her delegation to breakfast at his official residence shortly afterward.

The tensions come as aging Japan’s clout continues to dwindle by comparison with China. China’s economy overtook Japan’s in size about a decade ago to become the second largest in the world, and is now about four times as big, although gross domestic product per head remains far lower. China’s military spending was five times that of Japan in 2021, according to a SIPRI estimate.

Economic Ties

Xi and Kishida both called for building constructive and stable relations in brief messages read out at an anniversary event organized by business lobbies at a Tokyo hotel Thursday. A heavy police presence controlled access to the area, while right-wing demonstrators could be heard protesting nearby.

Japan and China have many reasons to maintain ties, not least the importance of economic links between them. Japan is China’s second-largest trade partner after the US. Bilateral trade hit a record last year as Chinese companies boosted imports, including of computer chips and the equipment to make them, which China needs to build up its own industry as the US tightens restrictions.

In addition, after Hong Kong and the tax-haven Virgin Islands, Japan was the single-largest source of foreign direct investment into China through 2020, according to government statistics. Companies such as Toyota Motor Corp. and Uniqlo’s Fast Retailing Co Ltd have all made big bets on the country since it started opening up in the late 1970s. In June there were still 12,706 Japanese firms that were present in the Chinese market, according to a study by market research firm Teikoku Databank.

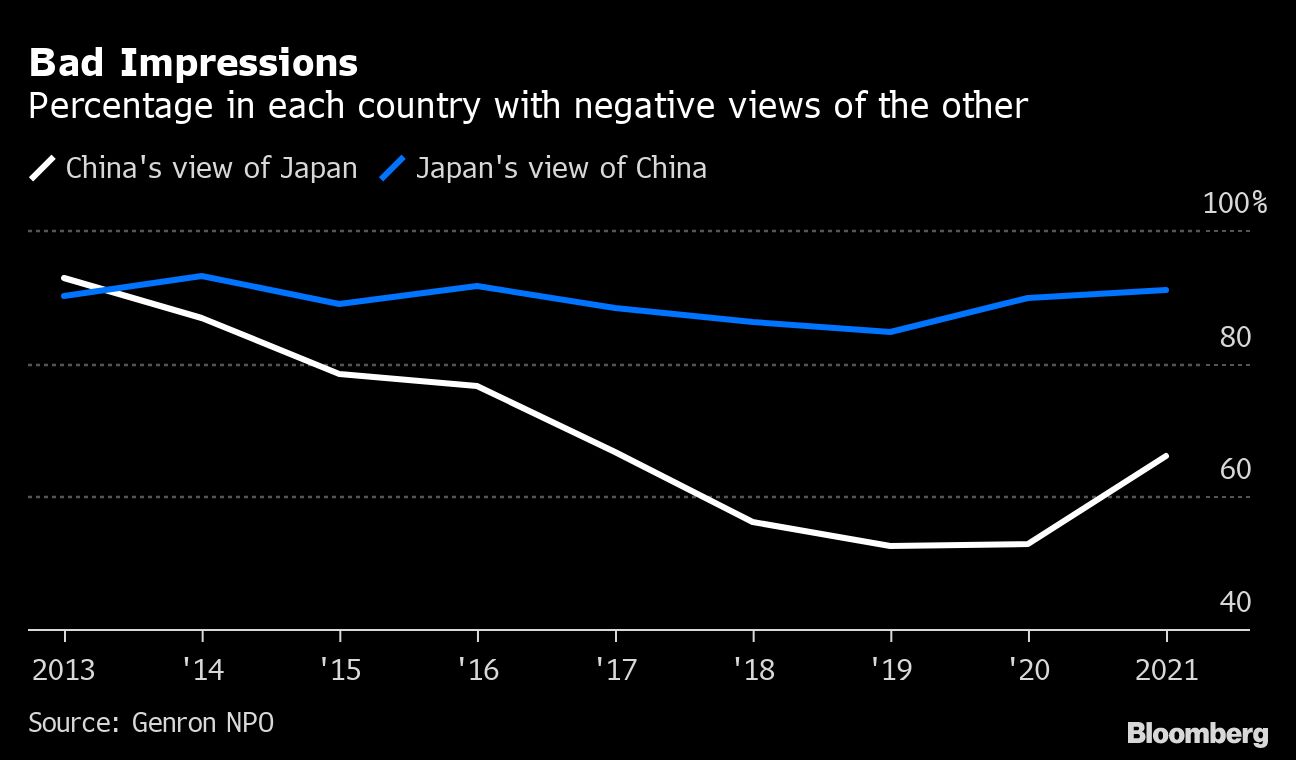

Japan’s tourism industry was also once a major beneficiary of Chinese visitors. They have been almost completely absent since early in the pandemic, which may have contributed to a sharp increase in negative feelings about Japan among Chinese surveyed by think tank Genron NPO last year.

More than 66% of Chinese said their image of Japan was “not good,” well up on the 53% who said that in 2020, according to the survey, making any move from China to improve ties less likely, even if the leadership wanted to.

“In order to persuade Tokyo to distance itself from Washington, China would have to make substantial concessions,” said Yinan He, associate professor in the Department of International Relations at Lehigh University in the US. “Chinese leaders are not in a position to make any of these concessions, especially before the 20th party congress,” she added, referring to the twice-a-decade leadership summit next month at which Xi is expected to secure a third term in office.

Yet, veteran diplomats warn that the two must continue to engage.

“In 1972, Japan chose this relationship, not conflict and division, but competitive coexistence,” said Yuji Miyamoto, a former ambassador to Beijing, and one of the backers of the anniversary festival. “How can we maintain and develop this relationship? If we can’t find an answer, our leaders bear a heavy responsibility.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.