Citing the need to combat the novel coronavirus, China is digitizing a method referred to as "grid management," in which cities are divided into grid-like sections for individual supervision.

The system provides people who are anxious about being infected or suffering from isolation with opportunities to seek consultations over social media and gain peace of mind, in a tradeoff for stricter supervision.

A neighborhood association for the digital age, the grid management system makes full use of both cutting-edge technology and China's tried-and-true tactic of throwing overwhelming human resources at a problem, making life more convenient while further consolidating the Communist Party's control over the lives of its wards.

-- Capillary action

On a visit to the Baibuting neighborhood in Wuhan, Hubei Province, where some of the world's first clusters of the novel coronavirus infections were found, a banner strung up across a courtyard urged residents to avoid in-person gatherings and instead use technology to keep in contact online.

In China, this sort of government messaging is carried out by "residents committees," which are roughly analogous to neighborhood block associations in Japan.

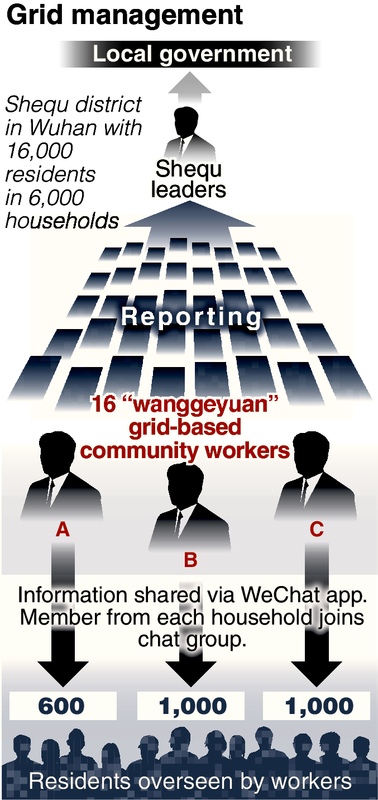

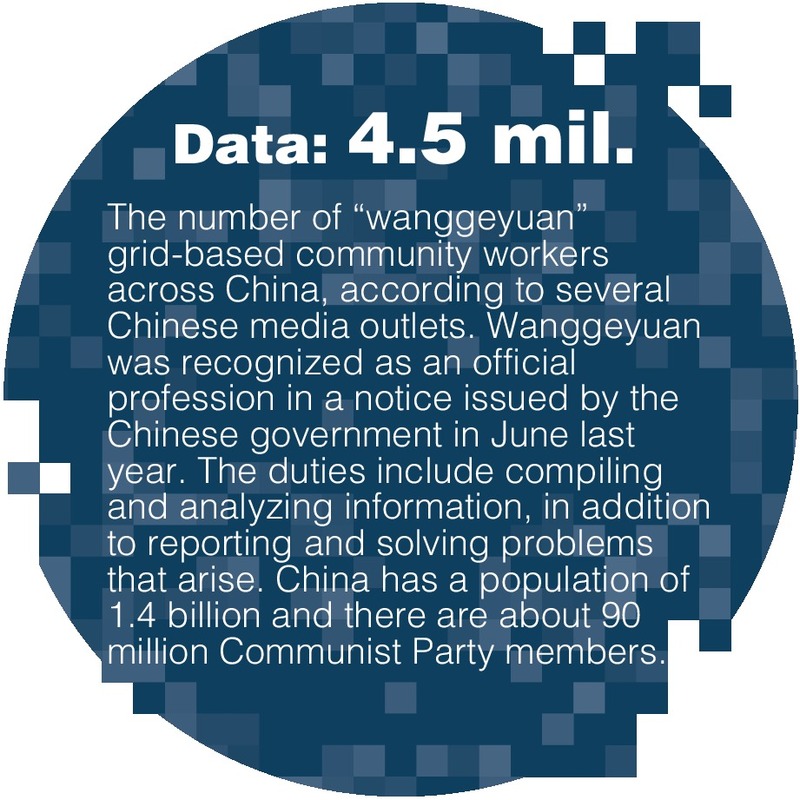

The work of the committees is carried out by "wanggeyuan," or grid-based community workers, who are the boots on the ground responsible for monitoring residents in each section of the residential district. The term "wangge" in Chinese means lattice or the squares of a Go board.

Districts under the jurisdiction of a residents committee are called "shequ." Wuhan has 863 such districts.

"If you liken a nation to a human being, we wanggeyuan are like the capillaries that extend throughout the body. We deliver information on residents to the government, which is the brain," said a man who supervises about 200 households, for a total of 600 people, in a shequ in central Wuhan that has a population of about 16,000.

Grid-based community workers are effectively the first layer in a sprawling network of government control. Becoming one requires passing an exam and being well-versed in socialist theory. Membership in the Communist Party is not a prerequisite for the job, but if the authorities spot talent in a community worker, they could be recommended for recruitment into the party.

-- Social work

The Chinese government has taken the pandemic as an opportunity to strengthen digital controls, retooling the role of community workers who used to primarily go door-to-door collecting information on residents.

Workers now rely on the social networking app WeChat, creating chat groups with the residents under their charge. When infections were running rampant in the community, they checked in with households daily to log the temperature of each family member and help distribute necessary supplies.

To residents worried about the virus, the workers have been a valued and dedicated social connection. "When residents were on lockdown and told not to leave their homes, I stood in line at the pharmacy for three hours each day in order to make sure people with long-term illnesses were still able to get their medicine," said one wanggeyuan.

Many Chinese appreciate the grid system. A 36-year-old woman in Beijing said, "If it weren't for the wanggeyuan always reaching out on social media, I think I might have been overcome with anxiety."

A 45-year-old man from Guangzhou said the system allowed him to "live with peace of mind."

As the pandemic subsidies, the grid-workers have transitioned to a consultative role, offering advice about residents' daily lives that builds on this accumulated trust.

On a given day, they may field a wide range of inquiries from residents looking for everything from plumbers to cram schools and even clinics that offer free infertility tests.

-- Neighborhood watchdogs

More than just welfare workers, the grid-workers also serve as informants. From the unfamiliar newcomer seen around the shequ to the visitor seen entering the home of the human rights lawyer, salient goings-on in the neighborhood seem to find a way to their sensitive ears.

According to a grid-worker in Beijing, the amount of information they receive has increased significantly thanks to social media.

Digitization has the effect of capturing residents' concerns in real time. Other goals are to snip the buds of dissatisfaction early and solidify government rule.

The information that is collected is transmitted to the residents committees and others using a dedicated app for easy collection by local governments and the police. A wanggeyuan from Guangzhou said: "We often compare notes with the police. Information on residents is incorporated into the police's big data dragnet."

While a wanggeyuan receives a monthly salary of only about 3,000 to 4,000 yuan (50,000 yen to 67,000 yen), there are many applicants for the job. A wanggeyuan in Beijing said, "I get the double joy of serving the people and also contributing to the government."

For the government, the grid supervision system offers a way to performatively reinforce the image of a "preestablished harmony" between the nation and the people -- to the dismay of human rights lawyers.

"People are easily seduced by convenience and safety. The CCP knows how to use human nature to their advantage, which makes them all the more terrifying," one lawyer said.

-- Big brother everywhere in Beijing

By Kiyota Higa / Yomiuri Shimbun Correspondent

BEIJING -- Living in China is to truly experience digital surveillance by the authorities.

On a late April day in Beijing, it took all of a minute before a familiar voice rang out in the taxi I had called with a ride-hailing app.

"This vehicle has recording equipment, and recording inside the vehicle is already underway," recited the monotonous, mechanical, high-pitched voice emanating from the driver's smartphone from its holder beside the steering wheel.

Presumably an automated recording played by the app responded to the start of the ride. The message had been preceded by a warning from the same smartphone, urging vigilance against bank transfer scams, in the deep voice of the Beijing public safety bureau.

The recordings were originally introduced to prevent crime. But the overlapping presence of the two different voices made it feel like the eyes of the state were upon me. After all, the app knows my name and other personal information. If the authorities wanted to, it would be a trivial matter to track that the customer on the taxi is a Japanese reporter.

Before ride-hailing apps started becoming popular in China around 2015, many of the taxi drivers in Beijing were eager to engage in spirited political discussions. Talkative drivers have become a rarity nowadays.

This winter, another foreign reporter climbed into the back seat of a car he had booked using a travel app to go from a regional airport to his destination. The reporter was surprised to see the ID of a public security official jammed haphazardly in the storage console between the driver's seat and the passenger seat.

Perhaps that is no different from in the past when the authorities used to monitor human rights activists and reporters. The only thing that has changed is the efficiency of the operation.

A person's movements can be tracked almost precisely by monitoring their social media messages and with the Chinese version of GPS. When added to old-style methods, nearly perfect surveillance is possible.

This raises concerns about causing problems for the people reporters interview.

One diplomat takes precautionary measures when meeting me by putting our smartphones in a small pouch that blocks radio waves.

The diplomat's country has a good relationship with China and the pouch is placed away from our table. Even still, I wonder if there are any "eyes" on us. No doubt the diplomat is thinking the same thing.

Read more from The Japan News at https://japannews.yomiuri.co.jp/